In Rangely, a town only four miles wide on the northwestern edge of Colorado, what matters isn’t on the surface. It’s what’s underneath.

More than a thousand wells surround the town, pumping oil and gas from below the high desert. A mine just east of the community of about 2,300 produces 2 million tons of coal a year, which is shipped by rail to a power plant in Utah.

Fossil fuels are the reason Rangely was first incorporated 75 years ago. The town now faces uncertainty about its future as the state and country move to dramatically cut greenhouse gas emissions from the energy sector and prevent the worst effects of global warming.

Without the fossil fuel industry, “I think Rangely would be a ghost town,” said Mayor Andy Shaffer.

Rangely is in one of 11 counties that are the focus of the Colorado Office of Just Transition, which state legislators created three years ago to support areas whose economies are heavily dependent on coal.

The office has given local governments more than $4 million so far this year for projects that could help replace jobs and revenues from the industry. During the 2022 legislative session, lawmakers approved another $15 million for the office.

“More ghost towns would be a failure,” the office’s Director Wade Buchanan said. “Ghost towns are a testament to the brutality of some economic transitions in our past.”

“I think we aspire to do this differently,” he said.

Colorado’s coal-fired power plants have already closed or are slated to close by the end of 2030. Craig and Hayden received millions in pandemic-relief dollars from the federal government this summer for economic development projects. The Inflation Reduction Act passed this summer also promises more generous tax credits for towns that replace their fossil fuel operations with clean-energy projects.

Rangely’s coal operations depend on regulations in Utah. Colorado’s move away from fossil fuels, however, has forced town officials to look at other assets that could keep the town alive, Shaffer said. This includes the local campus for the Colorado Northwestern Community College and a regional airport, which hosts the school’s aviation program.

Some people in Rangely think it’s time to look above ground at the economic potential that outdoor recreation has to offer. The industry adds $9.6 billion in market value to the state’s economy, according to estimates from the state Office of Economic Development and International Trade.

“I'm a recreation fanatic and I know how much money people have to spend on recreation,” said Jocelyn Mullen, Rangely’s town planner and engineer.

The industry’s jobs aren’t high-paying, she said, but it should be considered as part of Rangely’s attempt to broaden its economy.

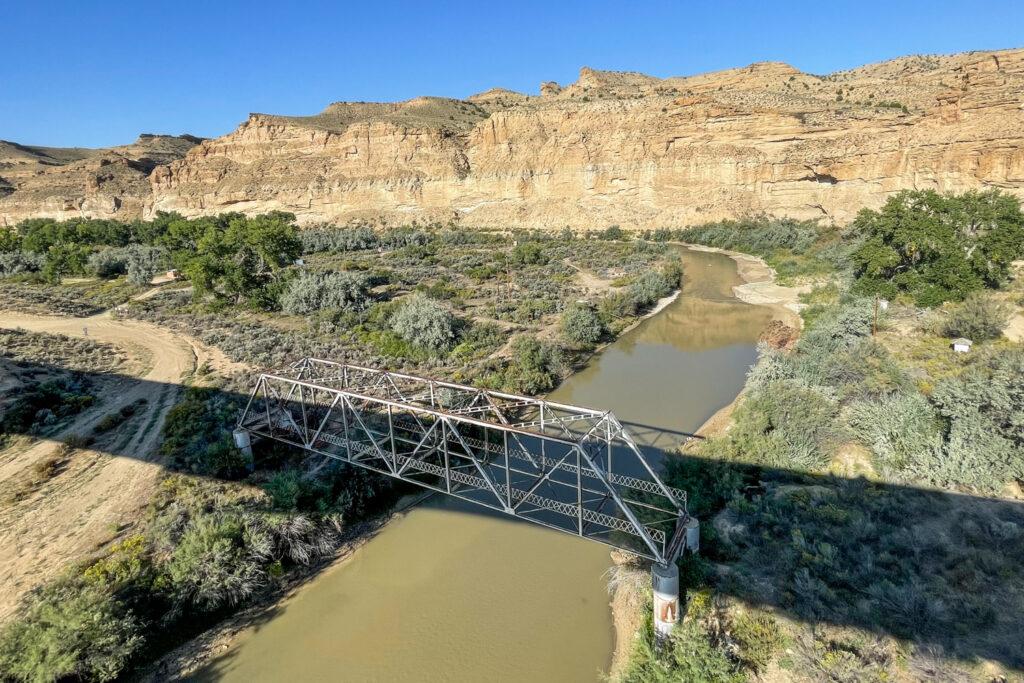

Rangely has already tapped into some of those activities, including off-roading and other tire sports. Mullen is now focused on mapping mountain biking trails and expanding access to another natural amenity: the White River, which extends from Utah into the White River National Forest but is hidden behind trees and tall brush in Rangely.

The state Office of Just Transition awarded Rangely nearly $400,000 this year to help build boating ramps and make the stretch of river more welcoming to kayakers, stand-up paddleboarders and rafters. Mullen, a self-described “river rat,” said the toughest challenge was getting others in town on board.

“People flat out told me things like, ‘We don't want spandex-wearing kayakers trespassing on our property,’” she said.

Town revenues from taxes and federal mineral leases dropped by 58 percent from 2019 to 2020, according to financial documents provided by Mullen. She said the decline led residents to rethink the economic potential of kayaking, including visitors buying food, filling up their cars or camping.

Mayor Shaffer arrived at the Rangely town hall on a recent Saturday night in a red four-wheeler with no windows and latching seat belts. He takes it on long trips with his daughter and offered to give this reporter a ride to see Rangely from a higher vantage point. Shaffer drove it slowly down the town’s main street, then accelerated with ferocity as he entered a dirt road and navigated up a rocky hill.

Earlier that day, Shaffer said recreation could only be a seasonal operation in northwestern Colorado, and could not make up the taxes and jobs from the year-round fossil fuel industry.

Others are more optimistic about its potential. Jen Rea, an associate dean at the Colorado Northwestern Community College campus and a friend of Mullen’s, said recreation and tourism could put Rangely on the map.

“I think the biggest thing is just getting us out there … and target the right audience,” said Rea, who paddles the White River often and visits the town’s other nearby features, including prehistoric rock paintings known as the “Carrot Men.”

Angie Miller, Rea’s colleague and friend, said she thinks about Rangely’s future after fossil fuels constantly. It’s one, she said, that won’t be dependent on just one industry, but on several.

“If I get really mired down in the fear of it, I'm not gonna do any good,” Miller said. “I'm not gonna be able to see the possibilities around us.”