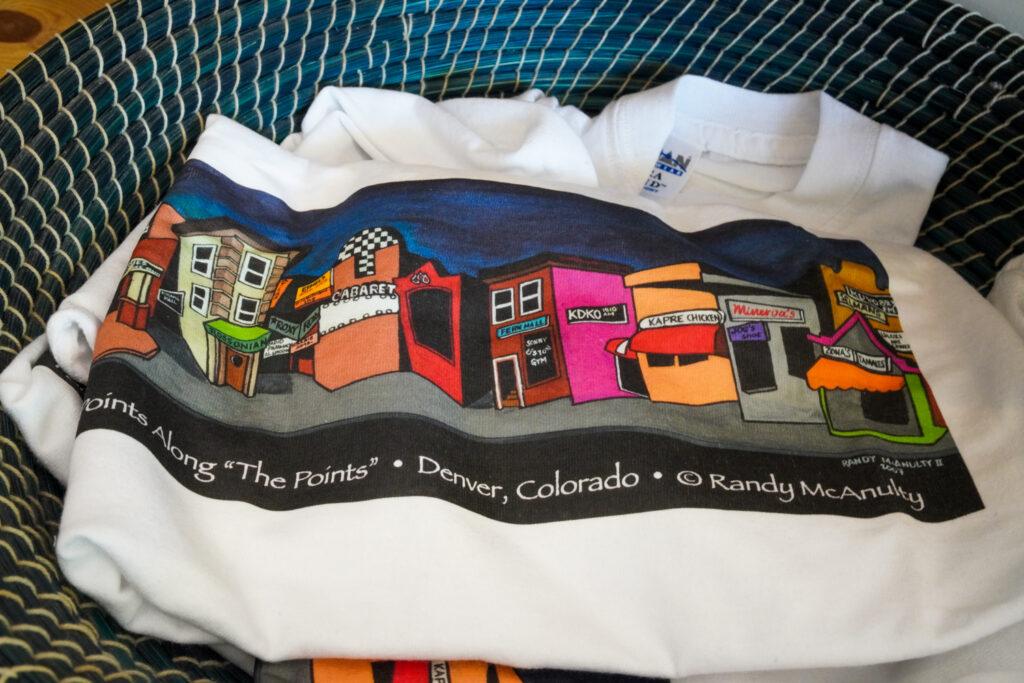

Risë Jones is walking around TeaLee’s, her three-year-old tea shop in Denver’s historically Black Five Points neighborhood. Soft jazz plays in the main seating area with about 10 tables, and in the basement is a bookstore with some hard-to-find titles by Black authors.

She started the tea shop about six months before the pandemic began, because she had fond memories of being served hot tea on a tray by her mother when she got sick as a child, and she enjoyed when her grandmother added orange juice to a hot cup of tea.

But while the shop is in many ways a testament to the past, there is no hint nestled among the soft decor that the seed money Jones used to re-open it emerged from one of the darkest episodes in world and U.S. history — slavery.

Jones is among several Black business owners in Denver who have received grants from groups raising private funds to pay reparations for the centuries of abuse of Blacks forced into slavery.

Jones decided to launch her own shop after falling in love with a tea shop a friend of hers owns in Lakewood, where the tea leaves are on display. Jones has her tea leaves in clear canisters behind the counter, so other people can see how different they are.

“I wanted the tea to be visible. So that you see the colors. You see the blacks, you see the green teas, you see some blends that have other things in them.”

She said she is always adding to her collection of tea-specific accouterments that include a condiment spoon — specially small-sized for little additions of sugar — and glass plates with frosted designs on which to serve cucumber sandwiches, some of them given to her by customers.

“A lot of the collection that we have in the shop comes from customers who say, ‘Oh, I have this set of China,’ or ‘I have this silver, and would you like it?’”

The shop is a repository of her memories, including pictures of her grandmother, who also gave her some dishes when she downsized from a house to an apartment.

Jones received an $8,500 reparations grant to open the shop, one of several that have been distributed.

'It kind of reshapes your perspective on your family history and family past'

Among those who have given to the fund is 63-year-old Tad Kelly, a Harvard-educated private equity investor in Denver who recently learned of his family’s slave-owning past and emerged determined to try and right the wrongs in whatever small way he can.

Kelly said that in 2019, when he was helping his aunt write up a family booklet with genealogical history, he came across a notation in her rough draft that eventually led him to a revelation: he is the great, great, great, great grandson on his mother’s side of an enslaver named John Doherty, who was born in the late 1700s and died around 1860. Coming across that was a game-changer, he said.

“It was a heart-stopping moment,” he explained, “because I just didn’t know that part of the family history. And when you learn of a fact that I consider very, very significant that you had been previously unaware of, it kind of reshapes your perspective on your family history and family past.”

Kelly was so reshaped that within two years, he found a well-known self-taught genealogist, Sharon Morgan, and the two of them took a road trip to the site of the former plantation. Together, they spent three days in Liberty, going through slave schedules, and marriage, birth and death certificates in local archives. After that, they explored the cemetery where the enslaved people were buried.

According to Morgan, the trip was a success: she was able to find some living relatives of his, meaning descendants of Doherty’s who were Black. During slavery, many enslavers raped enslaved women and then enslaved the children coming from these rapes. Morgan was able to find one such woman and her children. She got their names and contact information, and Tad Kelly has cautiously, respectfully reached out to them to have what could be a very awkward and sensitive conversation, and is awaiting a reply.

There’s no guarantee that the folks they found will have any interest in talking to him. According to Morgan, it could go either way, but it’s up to Tad Kelly to handle it.

“I do the research work and then I hand it off to the person who is my client,” Morgan said. “I will advise them and I can get involved if I have to, but I try not to, because part of the reparation is that this is something you need to do for yourself. I don’t want to be intrusive in that, because that’s part of the healing process. It’s like, you need to do certain things that I can’t do for you.”

In the meantime, Kelly decided he needed to do more than just help fund a memorial at the cemetery and wait to hear from his prospective relative. He returned with the idea of funding reparations grants like the one Risë Jones has received, because the trip and the knowledge he gained left him forever changed.

”I think once you learn about the history here and some of the facts, I just don’t think that you can see the world the same way ever again,” said Kelly.

'We have to be made whole in every aspect'

There are several organizations that do precisely that kind of work. One of them is BRIC (Black Resilience in Colorado) a non-profit organization that officially opened on Juneteeth (June 19) of 2020. It’s run by LaDawn Sullivan, who said the organization has already given out $2 million in grants to 136 Black-led and/or Black-serving non-profits in the greater Denver Metro area, including the Center for African American Health and the Park Hill Pirates, a youth football and cheer organization that’s been around for 60 years, They don’t limit themselves to reparations-oriented funding as a way to make amends for slavery, but one of their six areas of funding is “racial justice.”

“We really try to get away from compartmentalizing,” Sullivan said in a recent interview. “We are whole people, so in order to experience real equity, real reparations, we have to be made whole in every aspect.”

Sullivan said that some white donors expressed interest in donating due to their status as descendants of enslavers.

At the same time, she said, “We also have more traditional philanthropic institutions, foundations that are led by white people,” whose donations are also accepted, without putting slavery reparations at the forefront.

“We’re supporting Black-led and Black-serving non-profit organizations. We are supporting and providing capacity-building services, programs and assistance,” Sullivan said. “No one is telling us what our issues are. We are self-identifying our issues, and we are deciding how we want to address them.”

She said the average grant given out by BRIC ranges from $10,000 to $16,000, with the maximum being $25,000. Once the grant is given, the recipient organization then has the latitude to figure out how best to apply it.

“If you need to totally flip the script and do something different because it’s what the community demands and needs, you have the latitude to do that and we want to get out of the way,” Sullivan said.

The grant applications, she said, can be enhanced visually, if a person isn’t great with words.

“We want our applicants to have as much space as they need to tell their story, so we have incorporated an option for them to provide a video about their work. Why it’s important is because typically folks are tied to the words that are written on the page.”

That puts some potential recipients at a disadvantage: “Some don’t have paid staff … they’re doing this literally from their heart and soul.” With the video option, she said, “it’s open to them to really share from their voice what they’re doing, how they’re doing it and who’s being impacted by their work.”

'We want to look forward with what we're doing'

Another organization offering reparations grants is the Denver Black Reparations Council — that was the organization from which Risë Jones received a grant. Before the pandemic began, the council was in its embryonic state. Its future members were customers of her shop — that’s how she found out about the grant she got in September 2020’ she used it to hire part-timers and to get current on rent and utilities.

Arthur McFarlane II, chairman of the Denver Black Reparations Council, said funding is just one part of what they want to do. In addition to providing money so organizations like Jones’ can thrive, he said building community is also a goal.

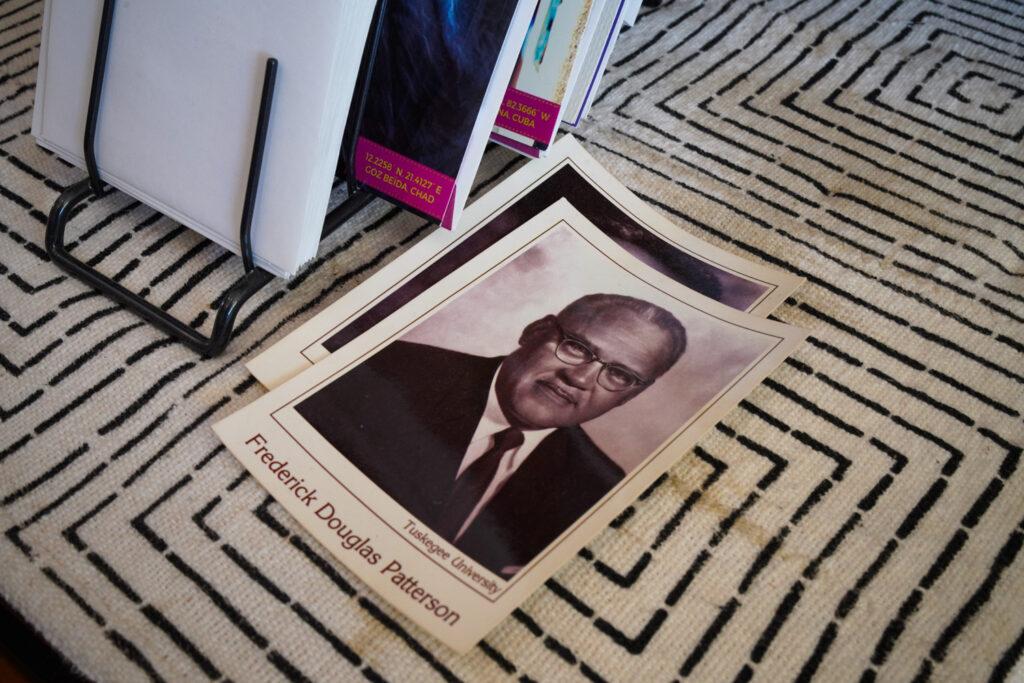

“In addition to soliciting dollars from individuals we would like to be able to open up the conversation that would really get people talking about reparations on the same page, going in the same direction about some of the same topics,” McFarlane said. “It’s not just about slavery. Some of the things that are our priorities are going to be building economic strength and generational wealth, preserving and expanding Black history and culture and knowledge.

“This is not an issue of, strictly speaking, looking backward. We want to look forward with what we’re doing.”

People interested in receiving grant funding from either BRIC or DBRC can apply through the Denver Foundation now. The application cycle for the next round of funding opened in early September and is set to close Oct. 18.

In addition to BRIC and DBRC, other organizations facilitating similar donations through the Denver Foundation include Reparations Circle Denver whose mission is to “rebuild institutions, religions, languages and traditions within the Black community of the Denver metro area as well as throughout the state of Colorado and beyond that were destroyed during the enslavement of African and African descendant people” and to “facilitate the reestablishment of Black institutions that were destroyed by the oppression that was imposed post-slavery.” Their awards, usually between $2,500-7,500, are given in the spring and fall, totaling $50,000 each cycle.

The organization Reparations4Slavery gives reparations grants and has educational guides on how to have conversations around reparations, as well as a primer on HR-40, the federal bill that would open a national conversation on reparations. Additionally, Coming to the Table, an organization to which both Tad Kelly and Sharon Morgan belong, provides classes on doing healing work on racial repair.

As Kelly awaits hearing from the relatives he and genealogist Sharon Morgan found during the trip to Liberty, Missouri, he continues to make donations through Reparations4Slavery that will benefit Black people, as a way to begin to create a balance between people with advantages like his, and people who haven’t received the same privileges.

“It’s the legacy of slavery that really forms the foundation of why we have in this country today, particularly, the racial wealth gap, which is the source of so much of the difference in opportunity to white people versus people of color,” he said.