Speaking with passion, prayers, reverence and determination, Native American tribal leaders described the atrocities they argued were set in motion by former Colorado territorial Gov. John Evans, for whom the mountain with the tallest paved road in North America is named.

Mount Evans, one of Colorado’s best-known 14ers, could get a new name by next year. The Colorado Geographical Naming Advisory Board started the months-long process in an online meeting Tuesday evening.

Many of those who came to make their case for a change had been waiting generations for the opportunity.

A tribal representatives-led meeting with the intention of educating the renaming council

More than 100 people showed up for the Zoom call, including Otto Braided Hair, Jr., who began the meeting with a prayer to honor the victims of the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre that killed hundreds of Arapaho and Cheyenne, including women and children.

“If you would join us to acknowledge those who have left us,” he began. “We believe they are still here and still seek their support.”

Then he spoke for about a minute in a Native language, finally adding, “A number of thoughts go through my mind and heart ... What’s heaviest is thinking and talking about the victims of the Sand Creek Massacre.”

Tim Mauck, deputy director of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources, made clear that the meeting was intended to be educational for the 15-member council.

“We are spending time in this meeting to listen and learn,” he said.

“We expect this to take a few meetings,” he said of the renaming process, which he has broken into steps: Tuesday’s meeting was for tribal representatives, several of them descendants of those slain at Sand Creek, to help the council better understand how the massacre impacted them. In the next meeting, people who have presented alternative names will be able to make their case.

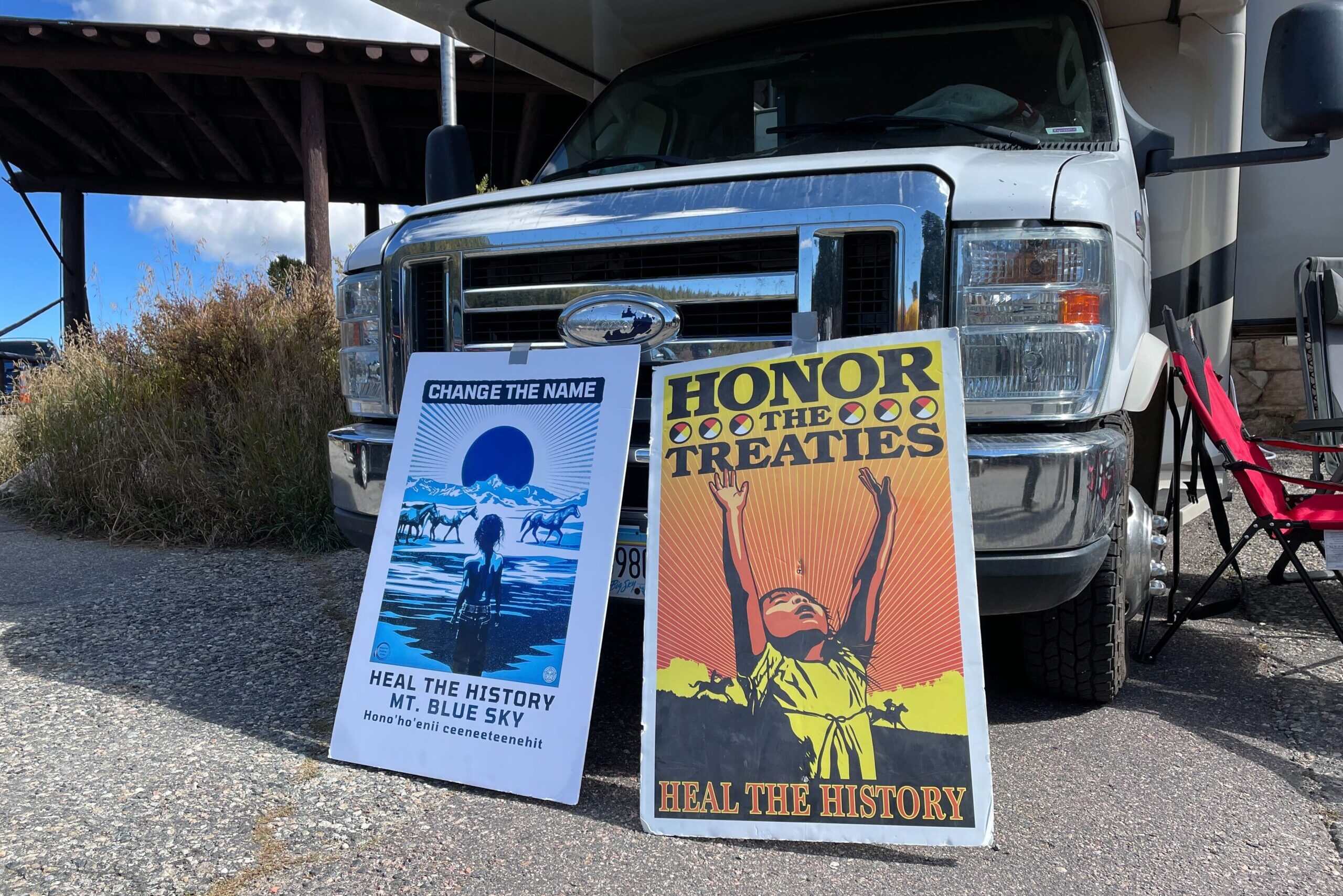

The tribal members at Tuesday’s meetings expressed support for two of the six names that the council will later consider, should a decision be made to change the mountain’s name. Mount Cheyenne Arapaho is one name the tribal members support; Mount Blue Sky is another.

An additional four names — Mount Rosalie, Mount Soule, Mount Sisty and Mount Evans (for the governor’s daughter) — have also been proposed.

At a later meeting, there will be a chance for public comment and debate. Then, if a name is agreed upon, it would then go to Gov. Polis, who could choose to accept it. After that, it would have to be approved by the US Board of Geographic Names. The process is likely to continue until 2023.

'We need to wipe that name off that beautiful mountain'

The name change is essential, according to both people who spoke in person and those who put comments in the chat function of the online meeting.

Braided Hair, Jr., who represented his Northern Cheyenne community, played portions of a 19-minute YouTube video that revealed that one of the victims of the massacre was a boy still in diapers, and another survivor could only find a relative’s pipe, but no relatives. He called it “the most tragic thing that happened to a group of Cheyenne at one time.”

Andy Masich, Historian at the Heinz History Center, also spoke. He described himself as a “historian, friend and consultant” to the tribes. He said that Indian leaders had come with a white flag of peace, seeking protection immediately before the massacre, but Evans abdicated his role to offer it, instead unleashing an Army to destroy all the property and people in sight. He said that even puppies were thrown into a massive fire while people tried to dig themselves into the creek bed for safety, to no avail.

“This all began because John Evans chose not to do his duty. He was complicit. He allowed it to happen,” Masich said. His voice remained measured as it increased in passion when he concluded: “Mount Evans is an affront to the Cheyenne and Arapaho people. It’s also an affront to the people of Colorado. It’s altogether fitting and proper that the name be changed.”

Conrad Fisher, cultural liaison to the Northern Cheyenne Tribal President, read a quote about the massacre from the US Joint Commission on the Conduct of War, written after a Congressional investigation determined it a "deliberately planned and executed, foul and dastardly massacre."

He added that it benefited Colorado while decimating Native country.

“Because of the site, there’s tourism that occurs. The local towns benefit. The tribes don’t benefit, but the state of Colorado does, because of the tragedy,” Fisher said. “However, we don’t have anything significant that recognizes the tribes.”

Ryan Ortiz, an official Sand Creek Massacre representative for the Northern Arapaho tribe, listed some reasons Evans was responsible, reading in part from the 109-page “Report of the John Evans Study Commission,” completed by the University of Denver in 2014. He said Evans advocated war over peace, deferred authority to the military, did not respond to a mandate to negotiate the treaty with the tribes, failed to resolve problems and ignored complaints made by Native people.

He concluded in an excited voice that when Evans had the opportunity to allay fears of Native people, “Evans instead chose escalation and panic.”

Next was Reginald Wassana, governor of the two nations, who didn’t mince words:

“He attacked us and basically murdered us and dissected us on the lands of the Sand Creek,” he said in an emotional address. “Land was taken over our blood and guts. Families were decimated and our tribe was decimated.”

Chester Whiteman, a leader from the Southern Cheyenne tribe, added: “We need to wipe that name off that beautiful mountain. It doesn’t deserve a name like that.” And of a name change, he said, “It won’t heal the hurt, but it will ease the pain.”

Though the virtual meeting included a public comment period, no one came forward to defend Evans, or the notion of keeping his name on the mountain.

Next steps

The next meeting, also online, will be on Nov. 17, at which time the two names that will honor the Arapaho and the Cheyenne, as well as the four other names, and the reasons for them, will be discussed, according to Mauck.

Later that month, a new exhibition — “The Sand Creek Massacre: The Betrayal that Changed Cheyenne and Arapaho People Forever” — opens at the History Colorado Center in Denver.