Every election, Colorado counties mail more than 3 million paper ballots to registered voters.

If you’ve voted here before, you know it’s a relatively straightforward process: You open your envelope, choose your candidates, close your envelope, sign it and drop it off. Then, on election night, the results come out.

But what happens to your ballot in between? And how are county officials making sure only legitimate ballots are counted in this process?

The answer lies in a complex system of checks and balances, security technology, legal regulations and a trained workforce of thousands of people. The measures in place have made Colorado a national leader in the eyes of some, and the target of intense criticism from others.

CPR News spent three months observing the ballot-counting process, including registration, tabulation and disposal. Our goal was to compile a comprehensive, fact-based review of the process to help you better understand what security measures are in place. The bulk of reporting that follows is from first-hand observation and more than a dozen interviews with election workers and officials.

Most of the people and photos you’ll see below are from the Arapahoe County Election Division, which gave us access to its main counting facility in Littleton. However, many of the processes there are identical to other counties, given strict statewide rules that dictate how elections are conducted.

Chapter one: Voting

The only way you can get a mail-in ballot in Colorado is to be registered to vote in the state.

Registration happens in a number of ways. You’re automatically added to the state’s voter roll when you renew your driver’s license. You can also update your voter registration at any time through the Secretary of State’s website, or by mail.

When it comes time to print your ballot for an election, county clerks pull your address information from the statewide voter roll. Then they mail your ballot, in an envelope with a personalized barcode, to your home through the United States Postal Service.

You’ll usually get your ballot several weeks prior to an election. For the 2022 midterms, counties will start mailing ballots on Oct. 17, giving you several weeks to complete and return yours by 7 p.m. on Election Day, Nov. 8.

As a voter, you have several options to choose from: You can vote by mail or take your ballot to an official drop box that your county has placed in your community. You can also vote in-person at a polling station or by absentee or military ballot.

If you vote at an in-person polling station, your county will automatically invalidate the barcode printed on the side of your mail-in ballot. That mitigates any chance that you, or anyone else, could vote twice.

If you vote by mail, your ballot will be delivered directly to your county’s elections division.

Editor’s note: In early October, Colorado’s Secretary of State’s Office accidentally mailed postcards to roughly 30,000 non-citizens living in the state notifying them on how they could register to vote. The state has emphasized that if anyone who isn’t a U.S. citizen tries to register to vote, Colorado’s online voter registration system will prevent their application from going through. Read about how the office is responding to the error.

Chapter two: Ballot collection

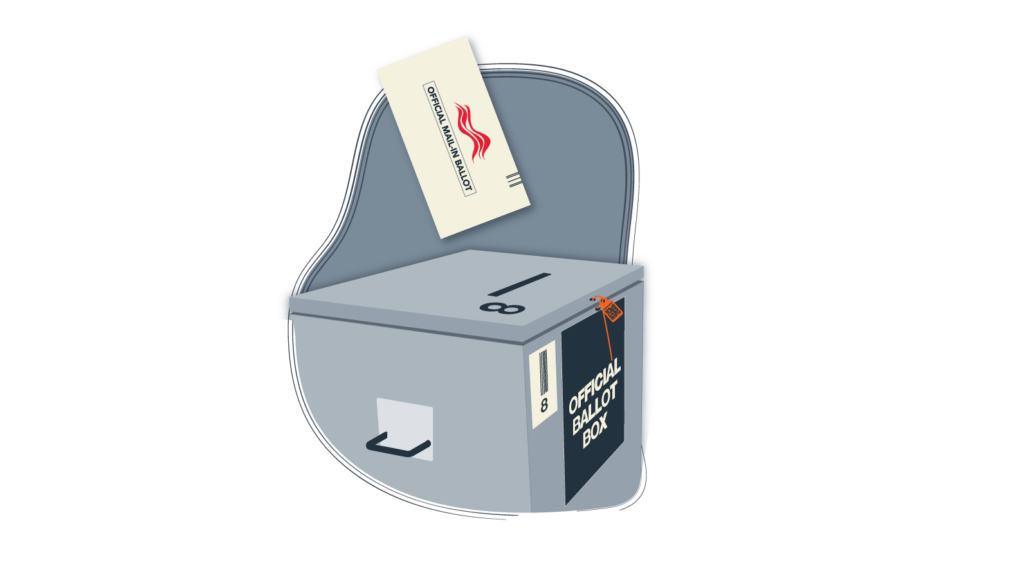

If you use a drop box, which more than 75 percent of Coloradans do, your ballot will be collected by a bipartisan team of election employees who work with your county’s election division. You can sign up for a statewide ballot tracking service called BallotTrax if you choose to vote this way. The service will update you via text or email after the county has picked up your ballot envelope and started processing it.

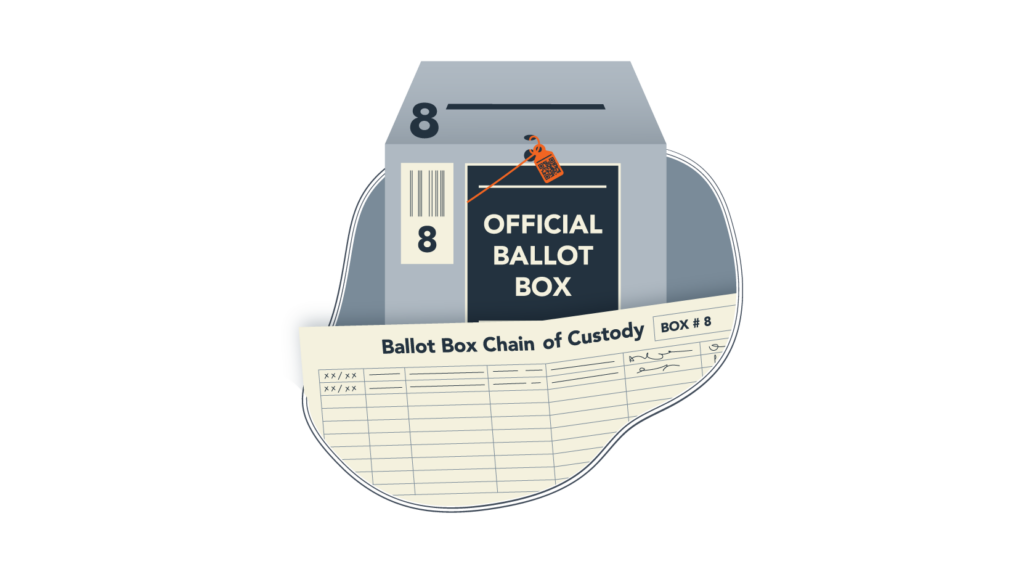

Together, a Republican and a Democrat will unlock the box and unload all of the ballots by hand. The ballots go into an official transit box that is locked.

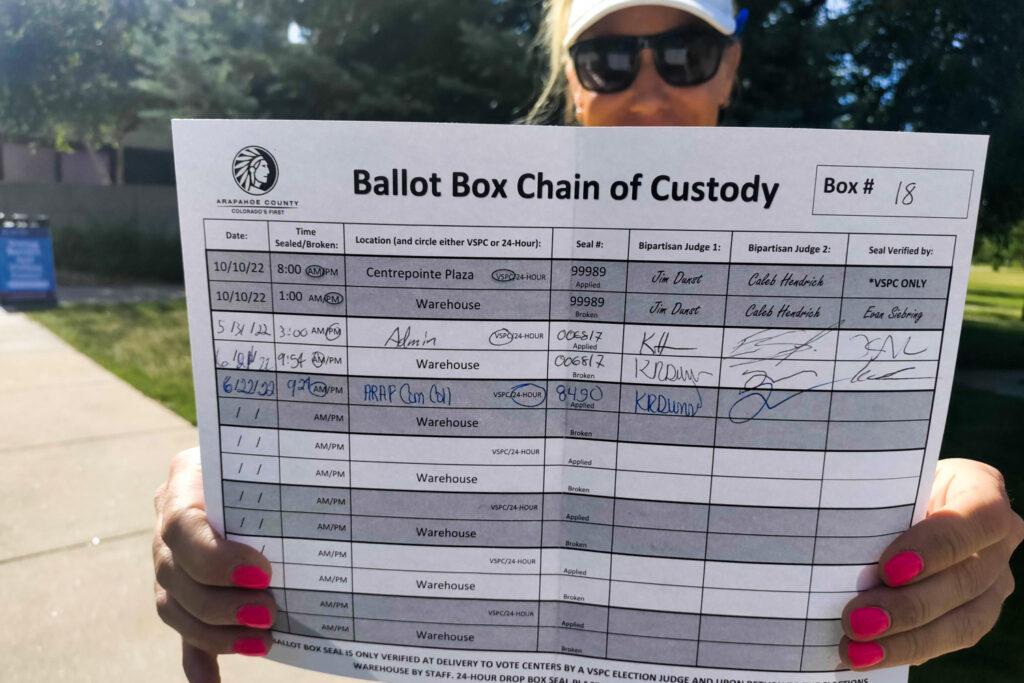

Both workers will then sign a “Chain of Custody” log, confirming the date and time they retrieved your ballot. Later, the county will scan and file the log as a public record.

We visited a drop box in Arapahoe County during the June, 2022 primaries to see this process in action. For those primaries, Lisa Heagney, a Republican, and Kathryn Dunn, a Democrat, worked as a team.

At a drop box on the Arapahoe Community College campus, Heagney pulled ballots out of the box and loaded them into the transit box while Dunn looked on.

“I think it makes it more secure when you have both sides present,” said Heagney, who applied to work for the county after the 2020 election. “There’s a lot of scrutiny right now of the system. That’s why I did this job.”

After double-checking that the emptied drop box was locked, Heagney and Dunn picked up the transit box. Together, they carried it to the Arapahoe County van they used to get around.

On this trip, they visited 10 drop boxes, repeating the collection process each time. Once their van was full of transit boxes, they headed back to the county’s main elections facility to hand off the ballots to another team.

Counties with smaller populations have fewer drop boxes, but similar bipartisan collection processes in place.

On Election Day, ballot security teams retrieve paper ballots from in-person polling places in a similar fashion. At the county’s main elections facility, the security team signs each box over to a receiving team. The two teams again make note of the transfer on the Chain of Custody log.

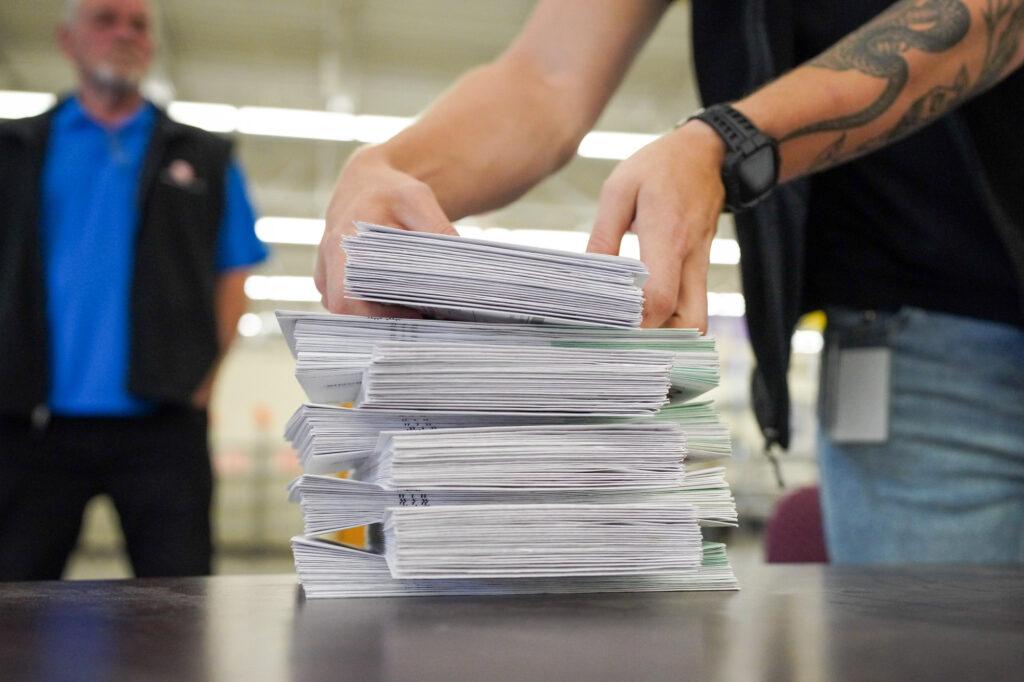

Workers then open the ballot transit box and unload the ballots from inside. They separate them into smaller batches for processing. For now, the envelopes will remain sealed.

Chapter three: Ballot verification

Next, your county will verify your ballot's authenticity using your signature and a barcode printed on the outside of the envelope.

Depending on how big your county is, the process takes place by hand or with a special ballot sorting and scanning machine. The most common type used in Colorado is called an Agilis, which is made by a company in Arizona.

Using a built-in camera, the machine takes a photo of the outside of your envelope. The photo looks for two important security measures.

First, software compares the printed barcode on the envelope with the statewide voter registration database to check if it corresponds to a registered voter. If there’s a match, then the machine sorts it into a stack of accepted ballots.

At the same time, a signature-verification program compares your John Hancock to ones already on file from state records, like your driver’s license.

If there isn’t a match for the signature or the barcode, then the machine will kick your ballot into a reject tray. There are other reasons a ballot could be rejected, including a damaged envelope or a ballot that gets returned without an envelope.

If your ballot does get rejected by the machine, a bipartisan team of election workers will examine it to determine why. But rejections are rare.

During election season, counties employ dozens of temporary employees who are trained in various aspects of signature matching. “It can get kind of tedious and repetitive, but it’s important,” said Thomas Benton, a signature verifier for Arapahoe County during the 2022 primaries. “Everyone here is vetted and dedicated.”

If the team still can’t determine a match, the county sets your ballot aside and contacts you through what’s known as a “cure process.” If you don’t respond, the county will not count your ballot, but they will send it to the local District Attorney’s office for potential fraud investigation. State records show fewer than .01 percent of ballots in elections are investigated for fraudulent signatures, though.

Once your ballot envelope is verified, either by the machine or through the cure process, election workers can open it.

Just like the collection process, ballot opening involves bipartisan teams of judges. One by one, the judges will slice open and remove your ballot from its envelope, then separate your ballot from its secrecy sleeve. Unfolding the ballot by hand, they will place it on a stack with other ballots.

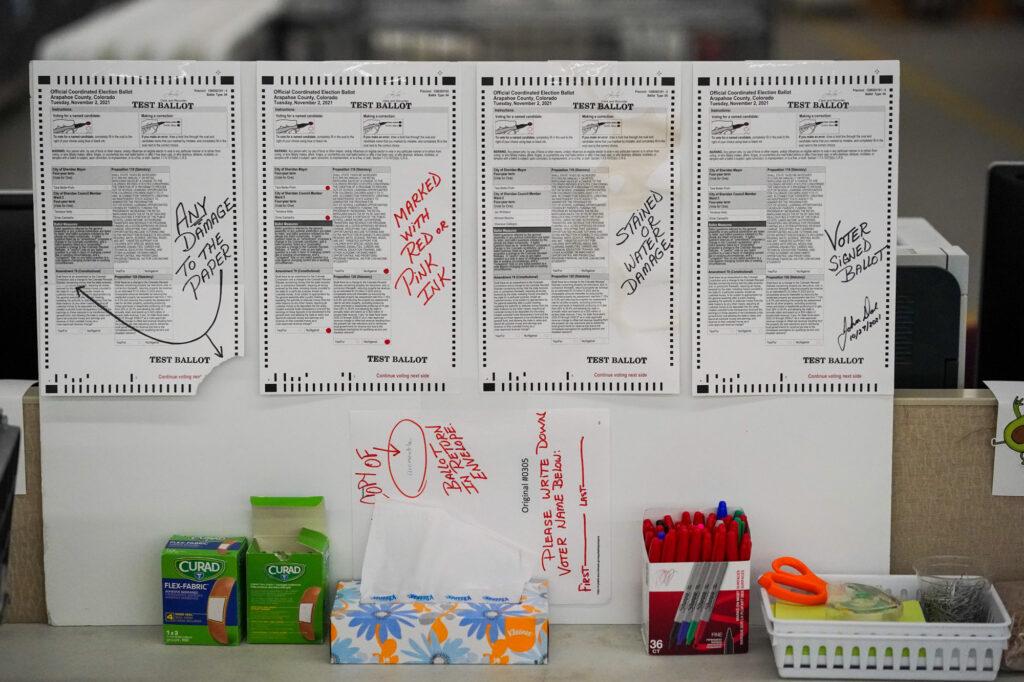

While doing this, workers give your ballot a quick glance to make sure there aren’t any water stains or other issues that may make it hard for counting machines to scan the ballot later on.

If everything checks out, the workers pass your ballot along to the tabulation team. That’s where the vote counting begins.

Chapter four: Ballot counting

After opening all of the ballots and placing them in stacks, workers give each stack a tracking log. The log is a piece of paper that’s used to keep a tally of the number of ballots in each stack. For example, if one ballot gets pulled from a stack of 100, the log is updated to reflect that there are 99 ballots in the batch.

The stacks of ballots are then placed in locked carts that workers roll to a secure room for scanning.

Here, a team unloads the stacks and feeds the ballots through a tabulation machine, which looks a little like a home printer. The tabulation machines use secure vote processing software and are never connected to the internet.

To count the votes cast on each ballot, the tabulation machine takes a photo of your ballot. Then, software reads the votes and tallies them up.

If the machine can’t read your ballot for any reason, the ballot is passed off to another bipartisan team to go through a process called “duplication.” That means the team copies your votes to a clean ballot in order to feed it through the machine. If that happens, the county will invalidate your original ballot, but will keep it on file.

Once the ballots are counted, county officials upload their local results to the state’s centralized Election Night Reporting (ENR) system. To do this, they use a new or clean thumb drive, which allows them to transfer vote tallies from their offline voting system to a protected computer.

At 7 p.m. on Election Day, the ENR software system begins to aggregate votes from around the state. Then it reports those results to the public.

Workers in county tabulation rooms aren’t able to see results while they’re loading ballots into the tabulation machines.

Once your ballot is scanned and counted, county workers prepare it for storage.

Chapter five: The audit

After the election, your ballot sits locked away for several weeks before it’s time to certify the results with an audit. This double checks the accuracy of each county’s voting machines, and is conducted by the Colorado Secretary of State’s office and county election workers.

The process kicks off with 20 different 10-sided dice.

Officials with the Secretary of State’s office roll the dice to generate a random sequence of numbers, or “seeds,” that determine which ballots county staff must audit; Dice help make sure the selection process is truly random.

In every Colorado county, bipartisan teams of election workers will pull the ballots that correspond to the seed numbers. Some counties record video of the process and even stream the audits online.

The workers take the ballots and manually enter their votes into a software portal managed by the Secretary of State’s office. The software’s code, which anyone can view online, was developed specifically for Colorado’s election audits. Its job is to compare the audit’s ballot entry to the ballot already on file from election night.

As long as the majority of the randomly sampled ballots match the count from election night, counties can assume with a high statistical probability that their tabulation machines accurately counted votes.

Colorado has required this type of audit for every election since 2017. Its main purpose is to ensure that the ballot tabulation machines are working and the reported winners are the actual winners.

The audit system often finds a small number of mismatches, called “discrepancies.”

The most common cause for discrepancies is human error during the audit, according to the Secretary of State’s office. Sometimes the election workers mistakenly retrieve a ballot that doesn’t match the seed number, or workers incorrectly input the choices from the audited ballot into the audit software.

Regardless of the reason, a special team in the Secretary of State’s office investigates each discrepancy and publishes a report online about their findings.

If a large-enough number of errors are found, audit workers must pull more ballots to evaluate whether the number of miscounted votes, or the “risk limit,” of the election is below an approved threshold. In Colorado, the risk limit changes each election, but it generally hovers around three percent. If additional auditing finds more errors, the process triggers a full recount.

That has never happened, however, according to the Secretary of State’s office. “The department has never found a single instance of the tabulation equipment not operating correctly when conducting the RLA,” said Annie Orloff, the office’s spokesperson, in an email.

After the audit wraps up, local elections officials, along with local party representatives sign off on the results. Then, the county can certify its election results and put the ballots back in storage.

Chapter six: Storage and disposal

Paper ballots take up a lot of space, and counties have to find a way to store them all.

Colorado law requires counties to keep ballots for 25 months after each election. That way, officials can have them on hand for recounts, public information requests or other needs.

The law doesn’t specify how the ballots should be stored, however.

Smaller counties use whatever space is available. Gilpin County, for example, uses an old county jail building to secure ballots behind locked cell doors.

Larger counties, such as Arapahoe, have more sophisticated systems. After each election, staff wrap batches of ballots in cellophane and lock them in special tubs. Forklifts stack the tubs on racks in the back of the county’s main elections facility in Littleton. Bins are organized by different colors that correspond to different elections.

Elections offices also keep digital files of each ballot on a secure server that is never connected to the internet. The files are part of the public record, so anyone could request them at any time after the election.

Once 25 months pass, county staff are free to dispose of the paper ballots however they see fit. A digital copy is kept in perpetuity.

In Arapahoe County, the preferred disposal method is shredding. The Littleton elections facility contracts a private shredding service to do the job a few times a year. One by one, workers ferry tubs of old ballots up to the shredding truck. Like a garbage truck, the vehicle whisks the bin up to an opening in its top and dumps the ballots inside where they are shredded into small flakes. When the truck is full, it’s taken to a recycling facility.

At this point, your ballot has fulfilled its democratic duty. And elections staff are busy preparing your next one for another round of voting.

Editors Note: This story has been updated to remove a line about QR codes being used to track ballot transit boxes. The QR codes were part of a pilot program and are not used statewide in every election.