During the pandemic, in every public school cafeteria in Colorado, every kid was able to get a free lunch, not just those from the poorest homes. Everyone.

The program expired.

Now a coalition of parents, teachers and anti-hunger advocates are pushing to make permanent universal free school lunches. Lawmakers in the Democratic-controlled legislature put it on the ballot. Next month voters will have the final say.

GlendaRika Garcia, a mom and bilingual food assistance navigator for Hunger Free Colorado, has no doubts about how she feels about it.

“I think that the kids being able to eat for free at school is really important, for all families, all kids,” said Garcia, a widow and a single mom of four boys.

Two of them, Alonzo and Pedro, tossed a football around in front of their Westminster apartment building, as Garcia explained her support for lawmakers putting The Healthy School Meals for All proposal on the ballot.

“Kids can't learn if they don't have good nutrition,” said Garcia, whose job entails signing up people for benefits and making sure they're eligible.

'It hurts my heart'

If voters OK Prop FF, it would create a program to offer free meals for all public school students and help schools pay for them. It would also fund pay increases for frontline school cafeteria workers, helping schools dealing with staff shortages and would incentivize schools to buy Colorado products. That has some families, workers and farmers cheering.

But some criticize what they see as a steep price tag for a new government program, which would raise $100 million annually from the state’s richest residents, if it passes.

Garcia sees the proposal as a game-changer, an equalizer. “I was a recipient of free school lunch when I was younger and oftentimes, before my mom even qualified for that, we didn't have enough for lunch,” she said.

A family of four making less than about $51,000 a year are eligible for free lunch. But supporters say right now more than 60,000 Colorado kids can’t afford school meals but aren’t eligible.

Depending on her job, Garcia at times qualified and at times didn’t, a blow to her budget.

“A lot of times, it's a financial burden for the parents,” she said.

Another issue, Garcia said some kids bully others for getting a free lunch. It happened to her as a kid, it happened to one of her sons.

“They know that people can identify if they can't afford it. It hurts my heart,” she said.

Her son Alonzo said at his high school some kids avoid the lunchroom rather than admit they qualify for free lunch.

“I think that they get embarrassed because they can't afford it,” he said.

The pandemic’s impact on kids’ school lunch consumption

Many Colorado districts reported a clear uptick during the pandemic of kids eating lunches provided for free at school.

“We were feeding kids that we have never fed before and it was good to see them coming up, and not just buying junk food,” said Andrea Cisneros, the kitchen manager at West Woods Elementary School in Arvada.

Many students arrive at school without food, said Dan Sharp, the school nutrition director in Mesa County School District 51 in Grand Junction. He noted that the pandemic gave a glimpse of the potential impact of a statewide universal free school meal program.

The district saw a 40 percent year-over-year increase in meals served during the pandemic, said Sharp, who prepared an informational letter about the proposal.

Before COVID-19, the district served an average of 9,500 of 21,000 students, about 45 percent of enrollment. During the pandemic, 4,000 more students ate healthy school meals daily than the previous two years.

“I really believe there's more households here and students that could qualify, but don't due to the stigma that goes with applying for free and reduced meals,” Sharp said.

He said today’s economy is having a big impact on the bottom lines of many. Families pay a higher percentage of income to housing and other key goods than decades ago.

Proponents said they did several food insecurity surveys throughout the pandemic and 44 percent of those respondents with kids at home reported being food insecure.

Recent national data found one in four families reported their children are not eating enough.

Colorado products from farm to school cafeteria

Colorado agriculture is a key part of the proposal.

Emerald Gardens is a farm in Bennett, about 20 minutes east of Denver International Airport. Roberto Meza walks through the greenhouses here, including one where a spectacular array of mushrooms is growing.

“Imagine children just enjoying the diversity of greens that we're able to grow here in Colorado,” he said.

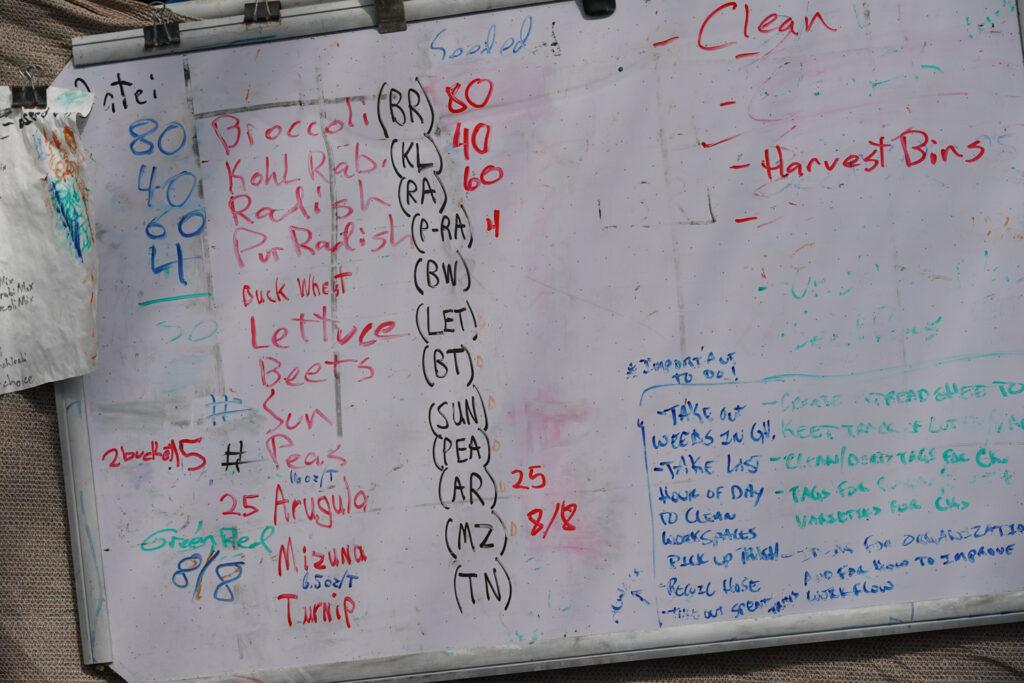

Super-nutritious microgreens filled a series of shelves, growing in water-fed trays.

“We got basil over here. We have some arugula over there,” said Meza as he pointed to rows of greens.

Agriculture can be tough, hard work, with lots of tricky variables. The measure would provide grants for schools to buy Colorado-grown, raised or processed products. If it passes, it would give a solid financial boost for farms like this while feeding kids, Meza said.

“It's our future generation, you know, they're our future leaders, so why not invest in them with the best nutrition possible?” asked Meza, the co-founder of the East Denver Food Hub, which aims to bring food to the community, at food pantries, restaurants, retail stores, schools and museums, while championing local farmers. Meza is also a commissioner on the state Agriculture Commission.

Kids at schools they now supply have been raving about the fresh local produce, said Meza’s partner in farming and distribution, co-founder Dave Demerling.

“It’s really about the kids eating this stuff. Like every time we get it to a school district, we always get great feedback and they're like, ‘why aren't we getting this normally?’”

The ballot measure comes as obesity rates are growing in Colorado and around the U.S. Diets lacking in good, nutritious food are a key factor, according to a recent national report from the Trust for America’s Health. Eleven percent of Colorado children 10 to 17 have obesity, a national survey found.

Concerns about the costs

Low-income students will still keep receiving free meals under current law, whether the proposal passes or not. There’s no organized opposition to the measure, but that doesn’t mean no one is opposed to it.

“Nobody wants to be evil enough to say it, but this is a really stupid idea,” said Jon Caldara, president of the Independence Institute, a libertarian think tank. “Most kids in Colorado do not need this. And in fact, those who do, already have this.”

The group’s voter’s guide recommends a no vote.

If it passes, the measure would raise $100 million dollars a year by increasing state taxable income, but only for the 3 percent or 4 percent who make at least $300,000 a year.

“This proposal is, ‘Hey, let's get the rich guys to buy our kids lunch,’ ” he said. “This is another expansion of state bureaucracy that is just not necessary.”

The governor told CPR’s Colorado Matters he hasn’t made his mind up about how he’ll vote on it.

“I don’t have an objection to the funding mechanism but at the same time I sort of ask myself, if we had this would it be better just to be able to pay teachers better, reduce class size?” said Gov. Jared Polis, a Democrat. “Or is the best use of it lunches for upper- middle-income families?”

He added that the measure “doesn't affect the state finances one way or the other because it's effectively revenue neutral with the mechanism.”

His Republican opponent sounded more supportive in her interview on the show.

“I haven't had a chance to look at it, but I do want to make sure that every child has access to healthy food and lunches, so I'm certainly open to it,” said Heidi Ganahl.

The Common Sense Institute, a nonpartisan free-market think tank analyzed the measure and raised several concerns.

According to the group’s ballot guide, if all Colorado public school authorities take part, an additional 615,000 students will now become eligible to get free meals, a rise of 125 percent.

Next year, 114,000 Colorado taxpayers will be taxed to pay for the program, with an annual average increased tax bill of nearly $1,000. In a decade, the number of Coloradans paying for the program is anticipated to grow to as many as 339,000 taxpayers, according to the analysis.

But the group’s modeling found funding could be higher than needed or too low to completely fund it. Surplus revenues could exceed a billion dollars in a decade or it could be underfunded to the tune of $330 million annually, according to its ballot guide.

“There needs to be some good oversight on the program so that costs are managed well, and also that they don't develop a huge surplus,” said Steven Byers, the group’s senior economist.

Proponents dispute that analysis, saying the institute seemed to multiply the cost of the program over 10 years, rather than the year-to-year funding analysis that shows how costs of the program are covered. They do acknowledge any leftover funding will go to the general fund, as any extra costs would come out of it. Based on the data and analysis done by the legislative council those costs “will be minimal and the proposal will create a long-term program with long-term funding,” according to Healthy School Meals for All Colorado Students.