The sun finally peaked out of the clouds over the White Mesa Community Center as a crowd of elders and toddlers, and activists of all ages, braced against the wind. Members of the Ute Mountain Ute tribe gather every year for the same purpose: to try to save their home for future generations.

Just outside the tiny community of White Mesa, Utah, sits a uranium mill the tribe believes is poisoning their land and people. Since 2017, they’ve held an annual spiritual walk and protest, demanding White Mesa Mill be moved or permanently shut down.

Like many who showed up here, Carl Moore is not from White Mesa. But Moore, part of the Hopi and Chemehuevi tribes, knew he had to drive in from Salt Lake City and bless the walk with a song.

“Basically, it's saying, you know, we're all related here,” he told the more than 100 people gathered around him. “Here we are, all of us. And it's a good day for us to be together.”

A bundle of sage burned at his feet as he sang to each of the cardinal directions.

The White Mesa mill isn’t just the only functioning uranium mill in the country. It is also a disposal site for radioactive waste from around the world. As the annual demonstration got underway, a car festooned with Indigenous flags played chants from a speaker and led a long procession onto Highway 191. People filled the shoulder of the main artery through southeastern Utah’s remote desert.

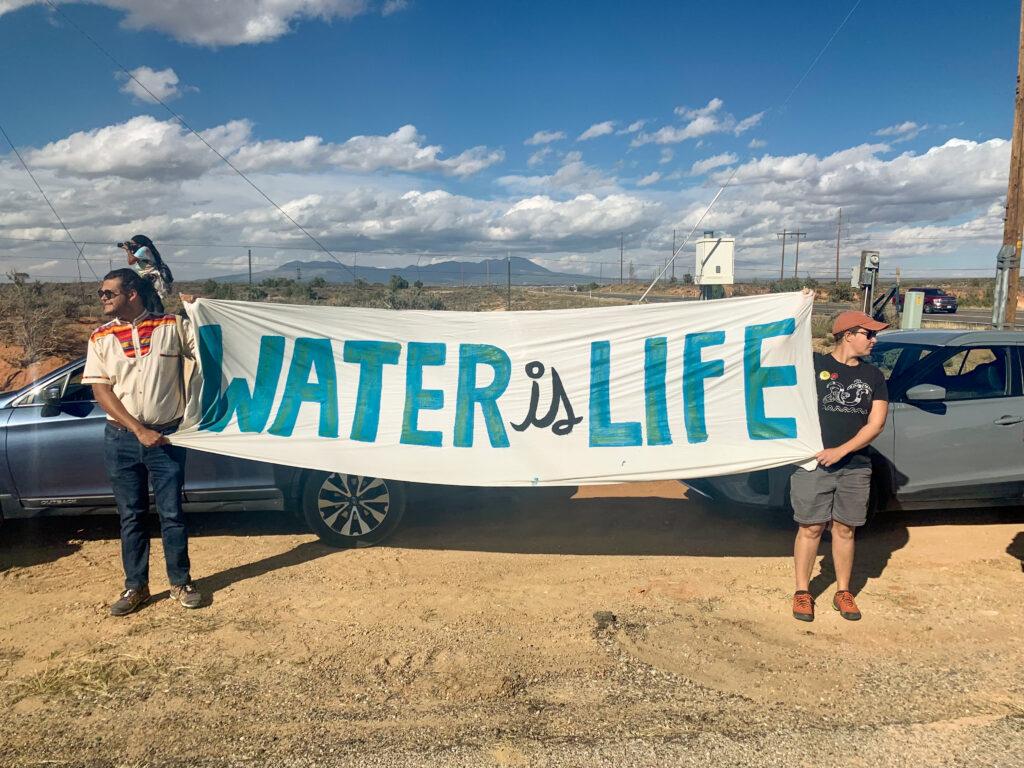

The protesters held up homemade signs and big banners, with messages like: “Keep Uranium in the Ground” and “Water is Life.”

Yolanda Badback, the protest’s founder, estimated this was their biggest walk ever.

“It’s amazing to see a lot of people, a lot of people from different tribes, who are out here to support,” she said.

Badback picked up the mantle of her late uncle, who also fought against the mill. Her brother, Michael Badback, said when the mill’s smoke stacks are going, “the smoke settles in White Mesa, and you can smell the sulfur.”

He blames the mill for increasing cases of asthma in the community’s kids and doing much worse to seniors.

“A lot of our elders mysteriously got sick, and a lot of them have passed,” Badback said, adding they still don’t know the cause.

NPR affiliate KSJD reports recently confirmed the tribe’s fear that radioactive contaminants have made their way into the groundwater. But the mill’s owner, Colorado company Energy Fuels, told the station it believes that is occuring naturally. A federally funded study on the mill’s potential health impacts is expected by 2025.

To those who support the mill, protester Rebecca Hammond had this to say: “Let’s put it in their backyards and see how they feel.”

Hammond lives in the Ute Mountain Ute capital of Towaoc, Colorado, but has family in White Mesa. She explained this land isn’t just where people live. It’s where they hunt and harvest plants for their medicine.

“You get everything you need out here. And when somebody else is destroying it for the sake of financial gain, you know, it's hard,” she said. “It's hard to try and be who your own culture is when somebody is still taking it away.”

The caravan of walkers, strollers and cars moved slowly, with several stops for water and snacks. A few hours later, they arrived at the mill’s turn off, where protesters stood under the mill’s big sign and held up their fists in resistance. A drone from an advocacy group buzzed above, shooting video and photos.

Michael Badback said he hoped the company and Utah legislators understand how serious they are about this.

“We just want our land to be safe and pure like it was hundreds of years ago,” he said.

No matter what, his family has vowed to keep the fight alive.