The Sonders project in Fort Collins looks like any other Colorado housing development — at first.

Concrete foundations sit next to newly paved roads stretching toward the foothills. Thrive Home Builders, the developer behind the project, has started to add wooden frames and roofs as it builds more than 200 single-family homes and townhouses.

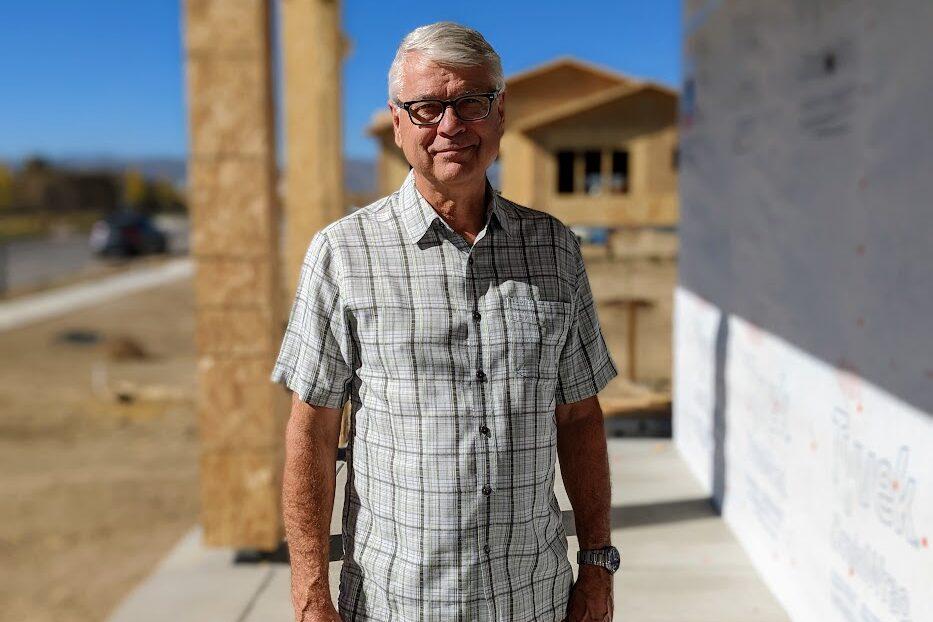

This project could mark Colorado's early attempt to end its long love affair with natural gas, which heats 70 percent of the state's homes. During a tour for prospective buyers, Thrive CEO Stephen Myers laid out the option to purchase a climate-friendly home built with an all-electric heating system and an induction stove. The final product requires zero fossil fuels.

"What's cool is you can make this home self-powered," Myers said. "You don't have to rely on anything other than the electricity from rooftop solar panels."

State utility regulators are now considering a proposal to nudge other builders away from natural gas. It takes aim at a long-standing financial practice: In Colorado and most other states, anyone who pays a gas bill helps fund incentives to connect new homes to the larger gas system. In effect, it means ratepayers and developers share the cost of adding people to the gas network.

Policymakers designed the subsidy decades ago to distribute the cost of expanding energy access. Now it's getting a second look as fossil fuels ravage the atmosphere. California became the first state to eliminate its subsidies earlier this year, citing rising energy prices and its ambitious goals to reduce climate-warming emissions.

Colorado could soon become the second. After releasing the proposal earlier this year, the state's Public Utilities Commission is set to make a final decision by the beginning of December.

Fueling a fight over housing and energy costs

That plan has sparked a debate over Colorado's rising cost of living. Opponents include the state's largest utility companies and housing developers, which argue eliminating the incentives leaves prospective home buyers facing even higher prices.

"All that does is add costs," said Ted Leighty, the CEO of the Colorado Association of Home Builders. "Right now, housing affordability is one of the greatest challenges we’ve ever seen in Colorado."

Xcel Energy, Colorado's largest natural gas and electricity company, currently provides a $741 incentive to developers to link a new home to the larger natural gas system. It later recovers those costs with fees from ratepayers. An Xcel spokesperson said the existing policy "maintains customer choice and affordability in new homes and businesses."

But environmental groups are skeptical that the incentives impact property prices. Market dynamics play a far greater role in determining housing prices, said Kiki Velez, a green building advocate for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Since most people aren't buying new homes, Velez said rising energy costs are a far more relevant concern. In California, state utility regulators estimated eliminating the incentives will save ratepayers $165 million a year. Colorado regulators don't have similar estimates, but Xcel Energy spends about $10 million annually to help connect about 14,000 new homes to its gas system.

"It's bad for customers, it's costing them money, and it's also completely contradictory to our climate goals," Velez said.

Environmental groups have further argued there's no longer a reason for the incentives, which were originally meant to expand energy access and spread the fixed costs of maintaining the larger natural gas system.

Those social benefits may have once justified additional costs for all gas customers, said Mike Henchen, who works for the carbon-free building program at RMI, a clean-energy think tank previously known as the Rocky Mountain Institute.

Now he thinks climate change has shifted the equation. If governments follow the advice of scientists, then they will pass policies to encourage residents to shift from gas to electric appliances. The recently signed Inflation Reduction Act could be an early example. Meanwhile, Henchen noted electric appliances, like heat pumps to provide heating and cooling, are getting better and dropping in price.

"If the idea at some point was that natural gas is an essential service to get to as many people as possible, that's just no longer true," Henchen said.

The practical points of selling all-electric homes

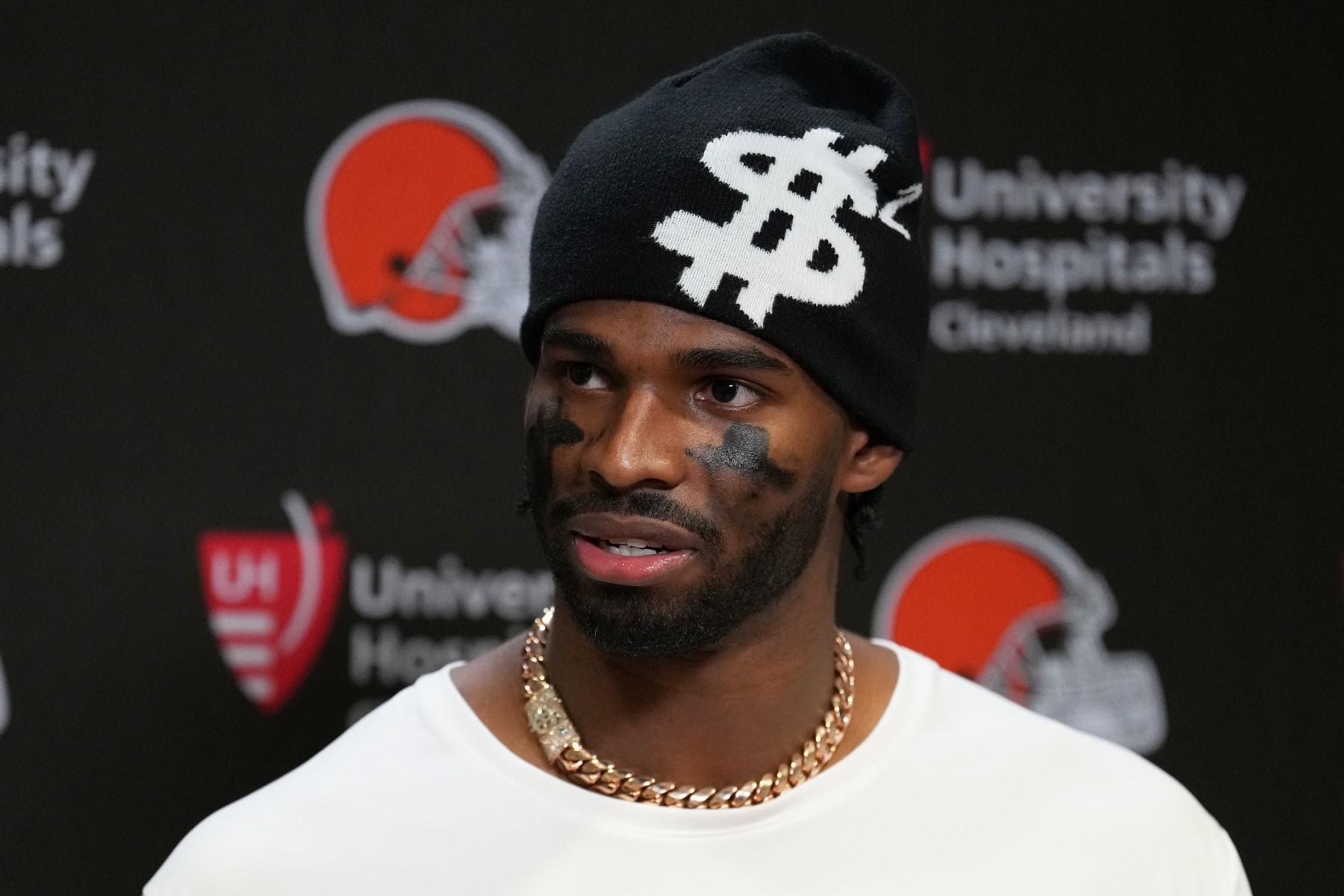

On the tour of the Sonders development, executives with Thrive Home Builders avoided the tense politics around natural gas. Prospective buyers in hardhats instead heard about potential consumer benefits of electric appliances, like avoiding indoor air pollutants and the potential for lower energy bills.

Lee and Beth Zimmerman didn't need much convincing. After moving to Fort Collins to be closer to their grandkids, they rented a home with an electric induction stove. They had to buy new pots and pans that worked with the cooktop but grew to like it over time.

"I think electric is definitely the way I would go, whether it's this builder, this house or somebody else," Lee Zimmerman said.

The couple agreed they’re willing to pay extra to ditch natural gas. Whether all-electric homes are more expensive in general is an open question. In their comments to utility commissioners, KB Home, one of Colorado’s largest builders, estimated electric appliances could add $27,000 in construction costs for a standard single-family home. Separate estimates from environmental groups — like RMI and the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project — show they cost less upfront and save thousands over time due to energy savings.

Gene Myers, the chief sustainability officer for Thrive, acknowledged their all-electric homes currently come at a premium. He thinks that’s fine since the Sonders development is aimed at aging baby boomers with disposable income.

Myers doesn’t know what Colorado utility regulators will do about natural gas connections in the short term. In the long term, he suspects local and state governments will recognize the construction industry, by one estimate, causes 40 percent of climate-warming emissions.

He suspects regulations requiring a shift from gas will follow. Myers wants his company to be ready to shape and handle the new rules.

"To me, it's inevitable," he said.