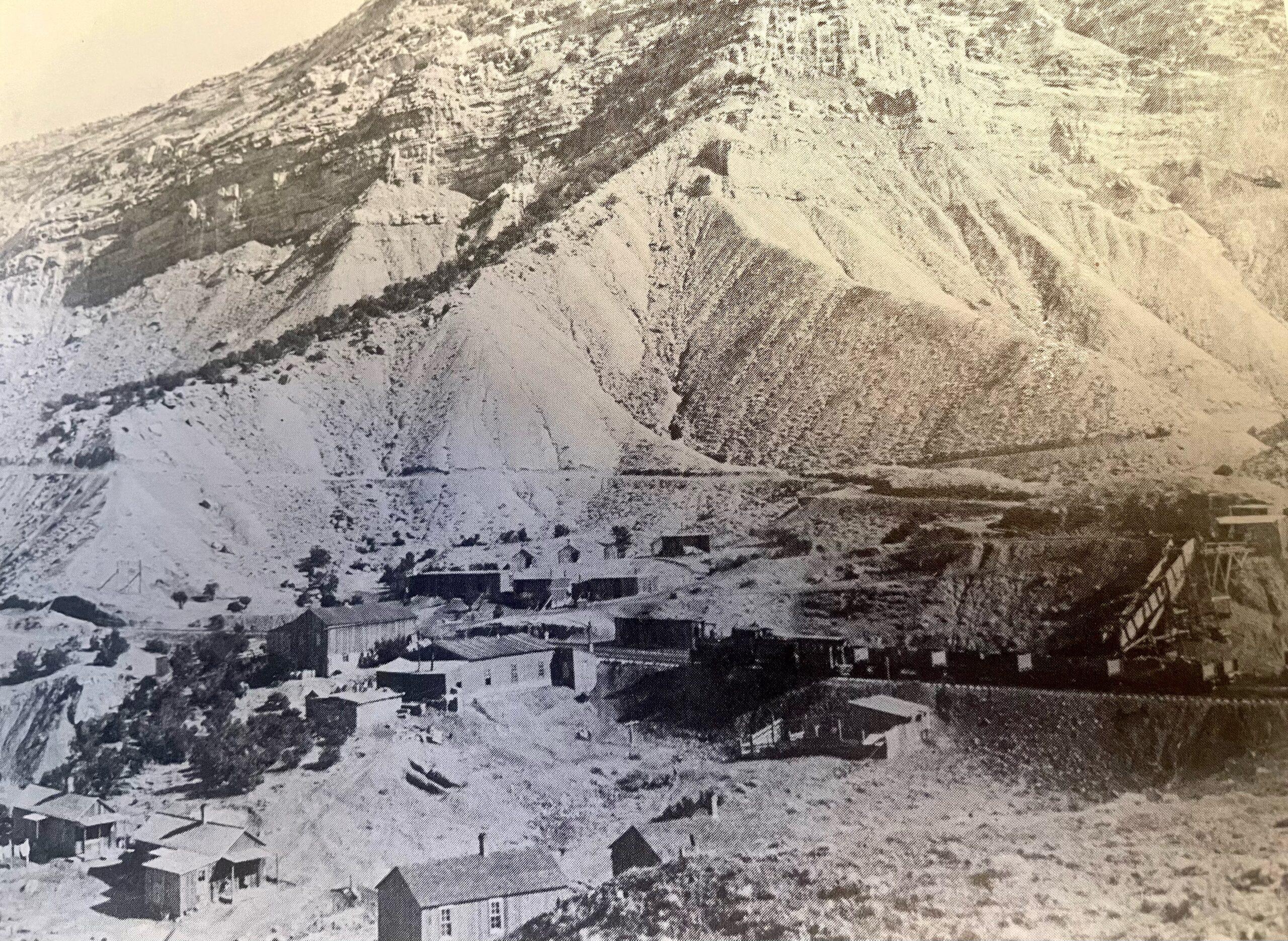

Mesa County is home to a ghost town that is as ghostly as it gets. The strange old town of Carpenter is nearly invisible these days out in the desert badlands at the base of the Bookcliffs, a mountain range that borders Grand Junction.

More than a century ago, Carpenter was a happening place. It was the worker community for two coal mines that fed the furnaces of nearby Grand Junction. Carpenter was also touted as an up-and-coming resort area, complete with a natural spring, fields of wildflowers, its own narrow-gauge train and a carnival-like railway contraption called the Go Devil.

It also had the lofty distinction of being owned by Princeton University for a time.

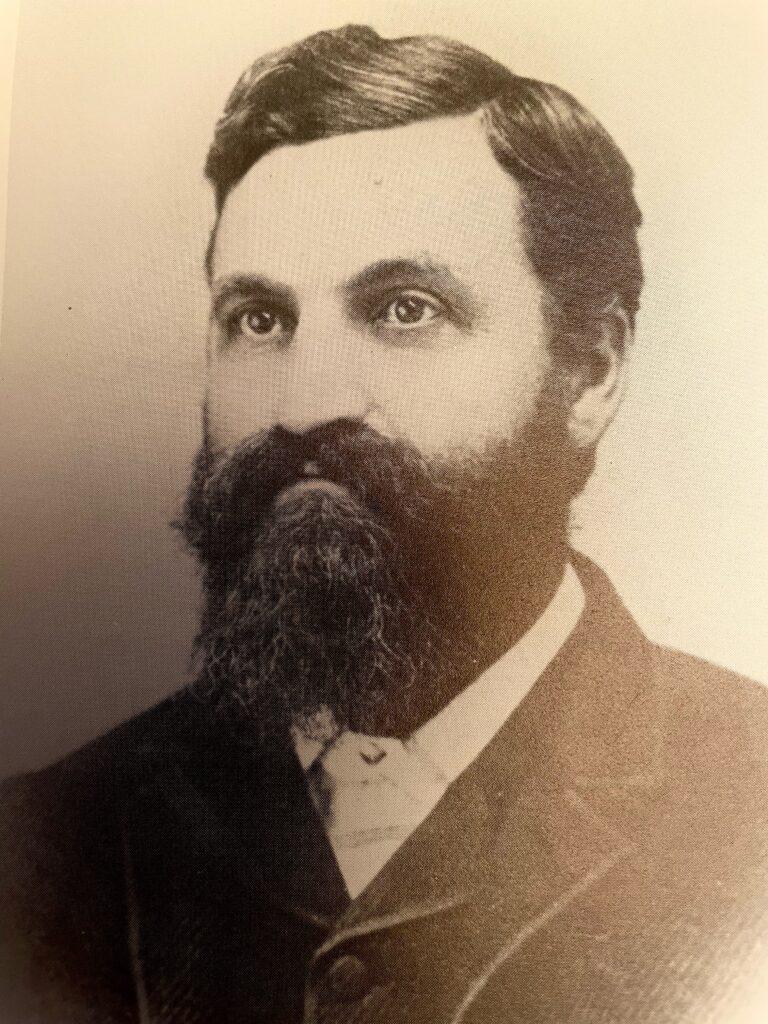

Carpenter grew from the mind of a boosterish businessman named W. T. Carpenter.

A 40-year-old coffee-table book called “Little Book Cliff Railway” details how Carpenter arrived in Grand Junction during the early 1880s and started a bank. He later bought two coal mines and called that operation the Grand Valley Fuel Company. The fuel company became one of the biggest business operations in the Grand Valley after Carpenter built ten miles of narrow-gauge railroad to bring visitors to and from the community he named after himself.

Carpenter’s railroad chugged right into the heart of downtown Grand Junction where he built a train station that, like the town of Carpenter, has now vanished.

Ike Rakiecki with the Mesa County Library has hiked around the scant remains of Carpenter, and he talked to Colorado Matter’s Andrea Dukakis about the ghost town’s story.

Rakiecki said that Carpenter — the man — claimed his community could eventually grow enough to overshadow Grand Junction as the largest town in the area.

Carpenter would bring trainloads of gussied-up people to Carpenter — the town — for excursions that involved picnics and wildflower gathering. Carpenter also planned to develop the local springs into an upscale spa. The springs inspired him to change the name of his town to Poland Springs for a time. He reportedly thought the name sounded fancy, like natural-spring resorts on the east coast.

The “healing” nature of the waters came into question when Carpenter started bottling and selling it in Grand Junction. It was said to have extreme laxative effects.

Carpenter never became a spa destination, and its population never grew much larger than 15 to 20 miners. The town had a few houses for families, a building for bachelors’ quarters, a bath house, a blacksmith shop and a few root cellars.

But the place hummed along as a tourist destination while Carpenter continued to promise explosive growth there. The 1893 stock market crash grounded those lofty goals and pulled the coal industry down with it.

Carpenter’s fortunes began to slip away. By 1897, he had lost nearly everything. He left his town behind and headed for the Yukon, where he ended up running a lemonade stand in Dawson, Alaska. He eventually turned that into a money-making lunch counter.

The town of Carpenter and its mines were taken over by a businessman named William Stanley Phillips. The locals called him “The Commodore.” He was the man behind the Go Devil, an open contraption that riders straddled while a locomotive pulled it up to Carpenter; Gravity brought it back down to town.

Phillips didn’t buy the town with his own money. It was financed by a wealthy uncle back east who left the bulk of his estate to Princeton University. The New Jersey higher education institution reportedly didn’t quite know what to do with an obscure coal mine facility in Colorado and tried to sell it. There were no takers, and the university ended up owning Carpenter for nearly 15 years.

The town’s potential was completely snuffed out by 1924 after a fire forced the mine to be sealed off. It dropped off the proverbial map until the 1960s, when some teens were exploring in the area and stumbled on what was left of Carpenter. Their discovery sparked a flurry of interest — and vandalism. Pretty much all that was left of Carpenter was carted away.

In 1989, Carpenter made the news again when three Grand Junction teens went inside one of the old mines and died from inhaling noxious gasses.

A plaque memorializing those teenagers, a piece of stone embankment, a few building foundations and spans of old railroad grade are all that’s left of Carpenter now. The remainder has been lost to the shifting sands of time in a barren patch of desert.