Antonio Matthews, Sr. scrolls through photos and videos of the January 6th riot at the U.S. Capitol on his phone.

In those photos, American flags, Gadsden flags and Trump 2020 banners filled the crowd as they surrounded the building that day.

But he’s not looking at a news site or a social media account. They are photos he took as he stood in the crowd.

“There were just slews of patriots there just simply wanting their voice to be heard,” Matthews said.

Matthews is Black and conservative and Republican. Most of the photos show him with other people of color, wearing a homemade shirt emblazoned with “Black Lives MAGA” on the front.

“There was a group of kids, one Black, one white, one Hispanic, all three of them had on Trump shirts,” Matthews said.

He tried posting the photos on Facebook but claims they were quickly taken down because of community standard violations.

“You can't portray that to the rest of the world, because it would show the unity that was actually going on instead of the carnage that they want everybody to believe that happened.”

Matthews says being a Black Republican is a foreign concept to most people, since Black voters are often pegged as reliably Democratic votes. Biden won 92 percent of the Black vote in 2020, and Democrats won Black voters by the same margin in the 2018 midterms.

The Colorado Secretary of State’s Office says there are 935,045 voters who are registered Republicans. Of those voters, 21,980 are Black, according to the Colorado Republican Party. It’s a small number — just over 2 percent of the state party.

Matthews says that political assumption is what he’s lived with most of his life.

“There was never any discussion on issues, no discussion on the economy, no discussion on policies, no discussion on anything other than [if] you're Black, you are automatically a Democrat,” he said. “And no matter what the issues are, every Republican is a racist, rich white man. And that's drilled into you as a kid.”

Matthews voted for former President Barack Obama in 2008, but was left unsatisfied after his first term.

“Nothing was done about jail reform. Nothing was done about police reform. Yet those are things that you campaigned on fixing and were supposedly very important to the African American community,” Matthews said.

Then, he started looking into the Republican Party.

“The more I tried to discredit them, the more I found myself intrigued by the facts of reality and history that the Republican Party was founded for Black people and by Black people,” Matthews said in referencing President Abraham Lincoln, who signed the Emancipation Proclamation to free enslaved people.

Colorado Springs resident Kendrick Davis took a similar path to the party.

Davis was politically unaffiliated most of his life. He grew up going to Christian Faith Fellowship Church in Milwaukee, the largest church pastored by a Black clergyman in Wisconsin.

When then-Senator Obama ran for president, Davis gave some serious thought about how he should vote.

“I started realizing just how on opposite ends of a spectrum the two parties tended to be when it came to my biblical worldview,” Davis said.

He decided not to vote for Obama after moving to Colorado in 2008. He now teaches a class on the U.S. Constitution at his church, the Church of All Nations. Davis says President Obama’s perceived focus on LGBTQ issues and abortion rights contributed to conservative Black voters looking for a political home other than the Democratic Party.

“It was right around Obama coming on the scene that we really started to see this push for same sex marriage, just things that were [against] my beliefs. And so, that was about the time that I started to really think.”

For some, the phrase “Black conservative” means a strong connection to evangelical Christian values

Family and faith are major influences for Black voters joining the Republican Party, according to current Colorado GOP Vice-Chair Priscilla Rahn.

“Black families are conservative traditionally in our values,” Rahn said. “When you think about family and fathers in the home and just being independent and prosperous and successful and just loving God and going to church, those are a lot of really strong conservative values.”

She is one of five Black vice-chairs in Colorado GOP history.

“I think for us Black people, when we look at politics, it’s not necessarily something we see ourselves in, because I think we’ve been told it’s only rich people,” Rahn said. “If you’re wealthy and you’ve got all these connections to DC, those are the kinds of people who run for public office.

“And then you realize, hold on, this is about ‘We the people.’”

Rahn believes Black conservatives have found their voice in the GOP, after the Black community’s long association with Democrats.

“Black Christian conservative movement exhibits many of the same value systems,” said Devon Wright, Assistant Professor of Africana Studies at Metropolitan State University.

“Throughout the Bible Belt — the Black churches — you're going to see a lot of Black religious conservatism,” said Wright, whose research includes race, ethnicity, conservatism and right-wing social movements. “That unfortunately sometimes can take the form of hostility to the LGBTQ+ community, can be very rigid in their understandings of gender relations, can even be very patriarchal and misogynistic,” Wright said.

More than 90 percent of Black voters across the country cast ballots for Democrats consistently each election. But that was not always the case.

Many scholars point to Democratic President Harry Truman’s inclusion of Black veterans in the GI Bill, as well as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — pushed by Democratic President John F. Kennedy and later signed by his successor President Lyndon B. Johnson — as a turning point when Black voters started to join the Democratic Party en masse.

During the 1960s, the Republican Party also embarked on what’s become known as the ‘Southern Strategy,' cultivating the support of white Southern voters over Blacks.

Some reference the War on Drugs campaign, implemented by Republican Presidents Richard Nixon and Ronald Regan and primarily targeting communities of color, as another reason why Black voters left the GOP and coalesced within the Democratic Party. As the Republican Party solidified itself to the right, the Black community became a pillar of the Democratic electorate.

Colorado Black Civic Engagement Commission Chair Johnny Watson was an exception to the rule. He joined the Republican Party during the Nixon administration. Originally a Democrat, he switched after serving in the military and stuck with the GOP through the Reagan administration. He attributes the move to his belief in Republican economic and fiscal policies.

“I stayed in [the Republican Party] for quite a bit of years, mainly because I was trying to force a change. People in the Republican party need to reach out to Blacks more,” Watson said. “I think they're trying to do that. The challenge that they have is within the party itself, there are people who don't really like people of color.”

Though still conservative, Watson began identifying as unaffiliated during the Trump administration.

“I left the Republican Party because the Republican party was leaving me. They left me,” Watson said. The party under Trump, he felt, lost the ability to even acknowledge, much less try to address, the racism of some of its supporters.

Dealing with the ‘elephant in the room’

Many people I spoke with admit that they have experienced some forms of racism as members of the GOP. But they say much of it sits behind closed doors. And all of them maintain they have found acceptance within the party despite its reputation among critics.

Derek Wilburn, the Executive Director of Rocky Mountain Black Conservatives, says the party’s racist perception still looms despite Black representation in leadership positions.

“You still heard the narrative from the media that Republicans have no Blacks, Republicans are racists, etcetera. Well, why are all these racists voting for all these Black people? When they have plenty of white alternatives on the ballot? Their answer to that question is that they aren't racist,” Wilburn said.

The Colorado GOP’s slate of state legislative candidates this year is more diverse than any in recent memory. Danny Moore, the party’s pick for Lt. Governor, is Black. Over the years, the party has put forward numerous Black congressional candidates, including Darryl Glenn, who challenged Michael Bennet in 2016, and perennial House candidate Casper Stockham.

Wilburn used to be a registered Democrat; He voted for President Bill Clinton in 1992. But he said Democratic Party values didn’t align with his Christian values. So, he migrated towards the Republican Party.

“The fact that you have dark skin, light skin, green skin, pink skin — what difference should that even make? We should adhere to the principles of conservatism and that as a Black conservative should be the same as a white conservative,” Wilburn said.

Wilburn founded the Rocky Mountain Black Tea Party in Colorado Springs in 2010 — it is now called Rocky Mountain Black Conservatives. The nonprofit organization is best known for its POC Internship program that sends college students of color to intern in Washington D.C.

“Pre-pandemic, we had a big presence on the streets, particularly in Denver, where we would go out and do neighborhood walks, participate in the Martin Luther King Day Parade,” Wilburn said. “We would always have a booth at the Cinco de Mayo festival — just meeting, greeting, shaking hands, kissing babies.

Wilburn says their focus was on “talking to people about the importance of political balance in the ethnic minority community.”

Many Black conservatives say they felt less at home among Democrats, where the party just assumed it would have their support instead of treating them as individuals with political agency. Now, as conservatives, they face open insults — often from the Black community.

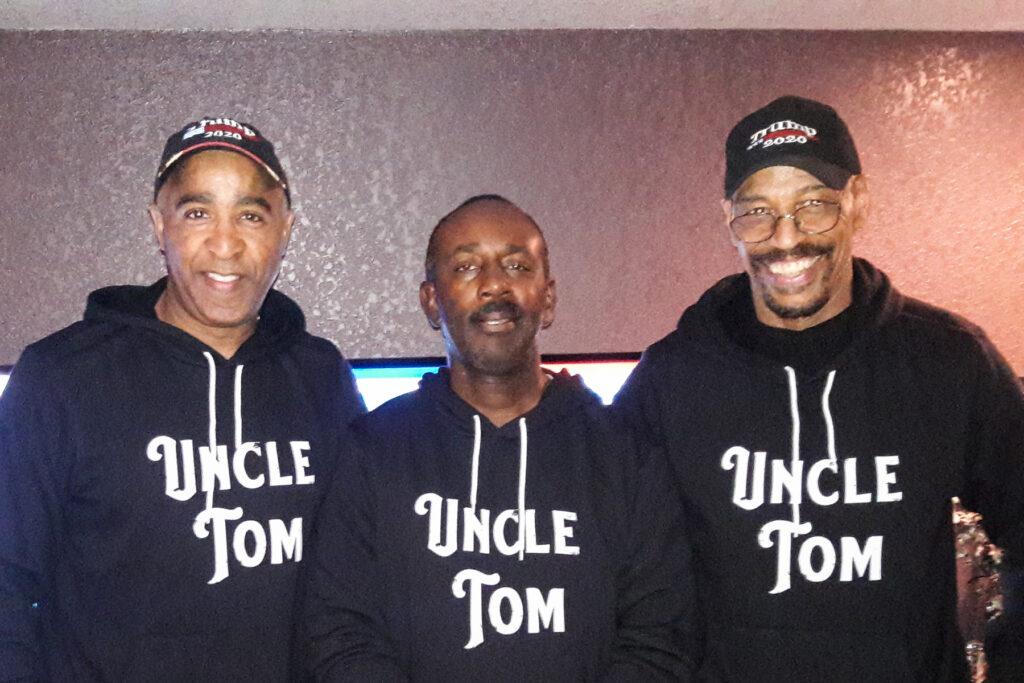

“But now, I’m an ‘Uncle Tom,’” Mathews said.

“‘Sellout,’" is what Wilburn said he hears a lot.

“‘You’re a coon,’” Rahn has been told, or, “Oh! You’re the Candace Owens of Denver.’”

“When I say, ‘What do you mean?’” Rahn said, “They can't really even explain because the only Black female conservative they know is Candace Owens, and they'd have never met another Black female conservative.

“I’m nothing like Candace Owens,” Rahn said.

When Trump came along, relationships with family and friends that had survived political differences started breaking down.

Matthews said he felt the effects of Jan. 6 right away.

“I posted some of those pictures on Instagram, and some clowns went and screenshot the pictures and then made posts all over Facebook, [to the] FBI,” Matthews said. “‘His name was Antonio Matthews.’ ‘He lived in Denver.’ ‘He was there at the Capitol.’ And then of course they showed up.”

The FBI searched Matthews' home and asked him questions. But because he never entered the Capitol building, he wasn't arrested.

Wilburn says it’s not Colorado that has not supported Black Republicans. It’s the Black community.

“I think in Colorado right now the Black percentage of the population is close to four. Yet, the Republican Party keeps electing Blacks to positions of leadership,” Wilburn said. “Which says to me that the narrative that Republicans do not support Blacks and are racist and all that stuff is nothing but a lie. In fact, it's the other way around. It's Blacks who won't support Black conservatives.”

Rahn points to the experience of the three Black Republicans currently serving in Congress.

“We've seen that at the federal level, where Black conservatives are not allowed to be a part of the Black Caucus. And, it's like, why are you excluding [us]? Isn't that the antithesis of what you claim to believe?” Rahn said. “So, it's the voice. They don't want to hear an opposing point of view.”

At the moment, there are no Black Republicans in the state legislature. Rahn hopes that will change with this election, and will give the Black community representation across the political spectrum.

“We're just not big enough to be so divided,” he said.

Editor's Note: an earlier version of this story inaccurately included Priscilla Rahm among Black Republicans who say they've experienced racism in the Republican Party.