Gov. Jared Polis, a Democrat, is set to serve a second term as the governor of Colorado after winning reelection Tuesday night.

He had campaigned largely on his first-term accomplishments on transportation, education and health care, along with broad promises to take on suburban sprawl and rising property taxes in a second term.

In early results, Polis held a commanding lead, with 59 percent of the vote. He had attracted more support in those early results than any other statewide candidate. Ganahl trailed by more than 250,000 votes as of 8:15 p.m.

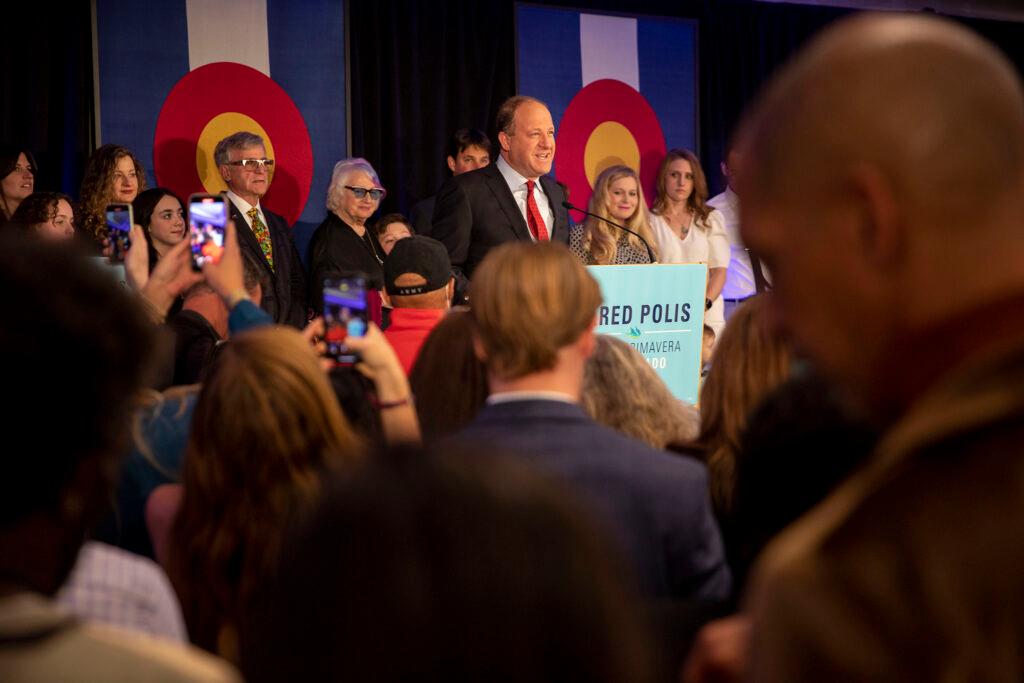

Polis took the stage just before 8 p.m. to give a victory speech.

“The fact is we did something simple. We focused on issues that really affect people's lives and we delivered real results. We focused on lowering costs and more freedom. We led with rational data-driven COVID policies that supported personal freedom and responsibility and resulted in Colorado having the ninth-lowest COVID death rate in the entire nation,” the incumbent told a room full of supporters at The Art Hotel in downtown Denver.

Polis defeated Republican challenger Heidi Ganahl, a businesswoman and an elected Regent with the University of Colorado. Ganahl had blamed Polis for recent increases in inflation and crime, and she also emphasized a “parents’ rights” message that pushed back against teachings around race and accommodations for LGBTQ students in schools.

Democrats have controlled the governor’s office since 2007.

Polis won his first term as governor in 2018, a “blue wave” election year, with ambitious promises to make kindergarten free for all families; build roads and transit; and reform health care. And over the last four years, he has signed new laws on those priorities and others.

But in this campaign, he made far fewer promises. Instead, he focused on how his administration is “saving people money” with actions it’s already taken. It’s a reflection, in part, of concerns about crime and inflation that have boosted Republicans nationwide.

“I think what people are looking to is proven leadership that understands the difficulties and pain people are going through and has a plan to make life better. And that's what we've done,” he said in an interview with CPR News earlier this year.

That message resonated with some voters, who saw Polis as a steadying force who had made measurable gains.

“I've been very impressed by him,” said Pam Curry, 72, a retired teacher from Grand Junction who is unaffiliated. She especially liked the incumbent’s moves to offer universal full-day kindergarten and limited free preschool for the first time in Colorado.

“I think that's one of the most striking things that has came to be under his leadership — and it's the future, really.”

Polis also argued that he would protect people’s freedoms, though he did not say the word “abortion” in his victory speech.

“Most importantly, we protected people's freedom, something we celebrate in Colorado. Freedom to love who you love, freedom to decide your own family's future,” he said. “Because in Colorado we offer something truly special. The idea that your choices belong to you and no one else. Our solutions are never based on whether they come from the left or the right or the middle or up or down, but whether they solve problems and make life better for Colorado.”

Instead of outlining numerous major campaign priorities, Polis raised just a couple big ideas for the next term. That includes his hope to encourage higher-density housing development near transit, and, separately, to permanently slow the growth of property tax bills. He also has floated the idea of replacing the state’s income tax with a tax on carbon emissions.

Separately, Polis has said that he will make Colorado “one of the 10 safest states in the nation,” compared to its current ranking of 21st worst for violent crime. He has pointed to increased funding for police and mental health reform as solutions.

But the governor also will face some tough fiscal obstacles in his second term. The state’s limits on government revenues, combined with growing expenses and the threat of a recession, means that there’s less money available for new programs in the coming fiscal year.

On the campaign trail, Polis only occasionally deviated from his central talking points — mostly to needle Ganahl. He attacked her for choosing an “election denier” as her running mate; mocked her for stoking concerns about “furries” in schools; and teased her for driving a Tesla despite her critiques of state investments in electric vehicles.

In their final debate, Polis described himself as a “happy dad,” while casting Ganahl as a “mad mom.” Ganahl has indeed referred to herself as a “pissed-off mom” and a “mom on a mission,” but Republicans said the governor’s jab was dismissive and sexist.

Coming out of the June primary, Ganahl, with her claim to fame as the last Republican left in a statewide office, was seen by many observers as the strongest in the field of potential challengers to Polis. And her fired-up campaign speeches won her devoted supporters like Cara Samantha Toney, 47, who had previously written off the Republican Party as being too weak.

“She's tough. She’s got some good ideas as far as crime,” said Toney, a registered Libertarian. But Ganahl appears to have fallen short with the moderate voters who could have boosted her chances.

Throughout the campaign, Polis returned to his geeky persona, including repeatedly singing a song about saving people money, which failed to draw laughs at a recent forum.

A campaign ad also focused on the governor’s tendency to mix brightly colored athletic shoes with his business suits. It was a nod to fashion habits that once drew him the distinction of “worst Congressional style ever?” Polis also is the first openly gay man elected to govern a U.S. state.

The two candidates had some limited areas of agreement. Both Ganahl and Polis want to see the state dramatically reduce its income tax, although Ganahl made that message more central to her campaign. And both are supporters of charter schools, although Ganahl wanted to allow public funding for private, religious institutions; Polis did not.