Ten years after first trying to tell the story of the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, History Colorado will try again, with an exhibit called “The Sand Creek Massacre: The Betrayal that Changed Cheyenne and Arapaho People Forever,” which opens to the public this weekend.

The first attempt in 2012 to commemorate the 230 unsuspecting victims of a U.S. Army attack in southeastern Colorado closed suddenly after just a few months, following an avalanche of criticism from tribal representatives who felt disrespected and excluded from the process.

Now it’s round two for the museum in downtown Denver. After a memo of understanding was signed by the tribes and the state in 2014, the publicly owned museum decided to create a new exhibit on the same subject, this time after years of input from the tribal members, many of them the descendants of massacre survivors and victims.

Representatives of the tribes — at least 100 are expected — will get a first look on Friday morning during a private walk-through of the museum, which will be closed to the public.

”They've taken input from the tribal representatives and they've kind of put that into that exhibit. It has a lot of pictures, it has a lot of quotes,” said Fred Mosqueda, a Southern Arapaho tribal elder who lives in Oklahoma.

With other tribal leaders, he spoke regularly with History Colorado over the past few years to make sure the story the exhibit told was accurate, inclusive and respectful.

“We’ve worked with them side by side.”

The 2012 exhibit left tribes feeling exploited because it included bullets and other munitions the US Army had attacked them with.

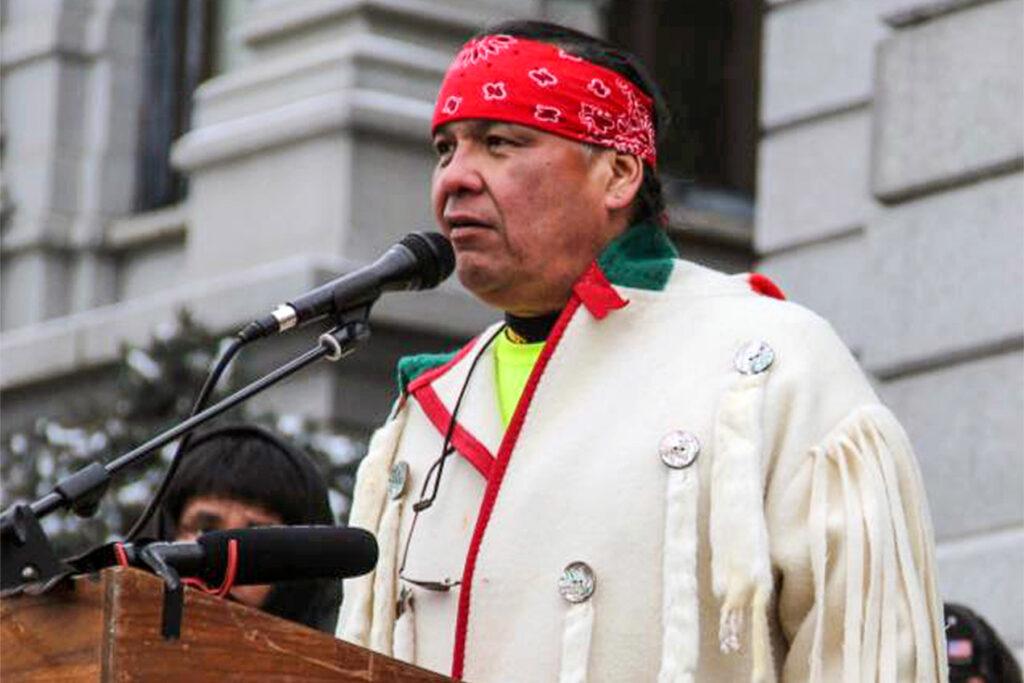

“One of the biggest issues we have is using a bullet that may have killed one of our ancestors, a baby, a woman, an elder or a chief could have been on the receiving end of these and have the blood of our ancestors on them,” said Otto Braided Hair Jr., a representative of the Northern Cheyenne tribal nation in Montana.

Of the first version, he said: “I’ve all but deleted it from my memory. I choose not to remember it. It was really disrespectful.”

Tribal members complained the museum didn’t show the humanity of victims, didn’t depict their physical bodies realistically and didn’t include materials that showed how they live today.

On Friday, Braided Hair, Mosqueda and dozens of other tribal members, elders and chiefs will find out if their input made a difference.

“We at History Colorado learned those lessons from what we did wrong in 2012,” said Sam Bock, lead exhibition developer. “This entire exhibit from the ground up, I’m talking from the color of the carpet and the walls to the content has been made in cooperation, in close contact, in close consultation with all of these tribal representatives.”

He noted how things are different from a decade before when he was in graduate school and not involved with the museum.

“History Colorado has changed its staff and changed its entire approach to working with these tribes,” he said emphatically.

This time, more of the exhibit’s components come from descendants’ voices and perspectives.

There’s a clip from a video interview that History Colorado recorded with Gail Ridgely, a descendant of victims of the massacre and a Northern Arapaho tribal historian. It was recorded at the site of the massacre and is one of several brief documentaries people can watch during the exhibit.

Visitors will also see traditional tipis, crafts and clothing. This time, there are pictures and videos of bullets and other armaments used — not the real thing like before.

On the ground floor atrium, visitors will see a Cheyenne-style tipi on one side and an Arapaho-style tipi on the other, to show tribes’ distinct identities — a feature that was lacking the first time.

The exhibit as a whole shares the fourth floor with an exhibit about the Ute tribal nation in Southern Colorado, although that tribe’s history is unconnected to the massacre. No outsiders have seen the exhibit yet, so it’s unclear if the museum has succeeded in presenting a more acceptable version of events. Curators are prepared to make last-minute changes if necessary.

“We will be listening and taking notes, and if there are concerns, if there are tweaks and modifications, we will do our best to make that happen in the next 24 hours,” said Shannon Voirol, project director of the five-person team that organized the show.

She mentioned that curators of the 2012 display, about a third the size of this one, don’t work at the museum anymore, and that the new team started from scratch, spending $600,000 on the 3,000-square foot exhibit.

The team visited the massacre site 180 miles from Denver about ten times, sometimes spending the night. On those trips, they met with tribal members.

“It’s really important that we understand the trauma that they’ve experienced from this massacre,” Voirol said. “And there’s no replication at all for being there with the reps and hearing directly from them ... This is not something that is just part of their tribal history. It’s something that they think about on a daily basis and causes real, actual present-day grief and pain.”

'I wouldn’t be involved with (the exhibit) if it wasn’t going to bring any healing.'

The new approach to the exhibit stems from a five-page memo of understanding between the Northern Cheyenne Tribe of Montana, the Northern Arapaho Tribe of Wyoming, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma and the state of Colorado, signed in 2014 by then-governor John Hickenlooper.

“It spells out that we will consult in a government-to-government, tribal/sovereign nation way with those three tribes on all matters of Sand Creek Massacre,” said Voirol.

That’s how it should be, said tribal members with personal connections to what happened 158 years ago, almost to the day. Mosqueda grew up hearing that his great-great-grandfather, called Mixed Hair, ran from the massacre holding his older sister’s hand, and that the two children’s parents were shot immediately thereafter.

“And the story is that the older sister seen a man that was laying in the bank ... and that man waved her and her brother over and pulled them into that hole ... and they laid there until the soldiers left and then they were able to get out of that hole,” he said, his voice filled with emotion.

He said that not everyone he grew up with heard stories about the massacre that included details — often young people who are elders now were only told that it was a sad day or a topic not to be talked about.

“Depending on who they are, how they were affected, how they were told these stories growing up is going to determine how they are going to react” to the exhibit, said Mosqueda, who anticipated an emotional day for some of the elders he’ll be escorting through the museum. “I'm hoping that being able to see it like this, that they will be able to feel better about themselves and their families, knowing well that we were still holding those that were lost in memorial.”

It’s a responsibility that he and Otto Braided Hair Jr. hold sacred. Braided Hair Jr.’s great-great-grandfather and great-great-grandmother, who was pregnant at the time, escaped Sand Creek. But hundreds of non-threatening women, elderly people and children were killed, and his life has been touched forever by the unresolved dishonor.

Several times during a recent interview, he got up from his seat in his home office for a moment’s break because the sentiments surrounding the massacre were so visceral.

“Just because somebody passes doesn’t mean they’re done with and we can forget about them,” he said. ”If they got the proper funeral services, then yes, they continue their spiritual journey. But if they don’t, and are at unrest, then it’s our responsibility.”

He added that a fabricated justification for the massacre was that the Cheyenne were “uncivilized,” which he finds unacceptable.

“A lot of my effort’s been just trying to show people that we were civilized; we were much more civilized than society in general,” he said.

When asked if he thought the exhibit would serve a purpose, he said, “Well, definitely. I wouldn’t be involved with it if it wasn’t going to bring any healing.”

'This exhibit, I think, is gonna say, ‘They are here.’'

Historian Andy Masich, former vice president of History Colorado, consults with the Cheyenne and has been involved with the exhibit-making process from Pittsburgh, where he now heads a similar history museum. In a recent interview, he called the museum’s new approach an achievement.

“This is a major shift, I think,” Masich said. “And so in that sense, I think this exhibit represents an evolution in thinking and in inclusivity.”

He said the past exhibit made it seem that the tribes, some of whose members were killed in the massacre, no longer existed.

“Rather than being frozen in time 150 years ago, and people imagine, ‘Well, they’re not here anymore,’” Masich said. “Well, this exhibit, I think, is gonna say, ‘They are here.’”

Although he can’t be sure yet, he said: “I think that this massacre exhibit will not be about death, but will be about life. About the life and times and hopes and dreams of Cheyenne and Arapaho people.”

Voirol expects that for the tribes taking it all in on Friday, it will be an emotion-rich experience.

“They’re all going to take turns having blessings in the gallery,” she said. “Those will last about an hour and half, and then together we’re having a meal and some talking.”

At mid-week, Braided Hair Jr. embarked on an eight-hour drive from Montana, where he is currently learning to teach the Cheyenne language while also engaged in solar energy projects. Bound for a hotel in Denver near the museum, he expected to travel through a snowstorm.

“We do so much traveling to Colorado for Sand Creek-related efforts. It’s treacherous between here and there and a lot of driving time,” he said. He added that he was fortunate to travel to History Colorado and represent his ancestors.

“There’s people that travel down the highway,” he said, “and don’t make it back home.”

The exhibit opens to the public Saturday, Nov. 19.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this story misspelled Andy Masich's last name. It also incorrectly referred to which floor the exhibit was on and where two tipis can be found. It also contained incorrect official titles for Shannon Voirol and Sam Bock.

History Colorado and the Sand Creek exhibit underwrite programming on CPR.