It was 1989, and 22-year-old Abron Arrington came home after spending four years in the U.S. Air Force. He was home in Colorado Springs after studying for nine months in preparation for a test to become a certified aircraft mechanic.

He was a good kid, his family said, a nerd even, and his criminal record was squeaky clean. So when he was arrested two days after returning home from service, it changed him and his family forever, he said.

According to Arrington’s sister, Mia Arrington, navigating the justice system and feeling powerless to do anything was too much for their mother, Roberta Harris, and their father, Chester Arrington.

Arrington’s father lived in Colorado Springs but ended up moving to Vegas after his son’s incarceration.

“He couldn’t take the pain of it,” Mia said. Their mother Roberta shut down emotionally and stopped visiting family members and being around people, she added. Arrington and Mia both said they still struggle to sleep at night sometimes.

But Arrington’s experience is not typical, and his struggle with anger and his family’s devastation is common. People who are incarcerated often deal with anger, pain and hopelessness — but that emotional toll is not limited to them. Their loved ones — mothers, sisters, children, friends also feel the long-lasting psychological impact of serving time.

The fight for justice

Arrington ultimately served 30 years in Colorado’s Department of Corrections for a murder committed by his cousin, James Carroll. The state argued Arrington was at a house where the homicide occurred and that he participated in a burglary. He was charged with first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison in 1991.

But Arrington played no role in the crime and was not even present for it, he said.

As the years rolled by and all of his appeals were denied, Arrington said his heart and mind was crushed, and so was his family’s hearts and minds.

Anger consumed Arrington during the early years of his imprisonment, and he said he dared anyone to challenge him about it.

He said he was at one of the most violent prisons in the state at the time — the Limon Correctional Facility. Arrington was among the first wave of inmates at the facility on the Eastern Plains after it opened in 1991. He said he was the first person to live in his cell, also known as a pod.

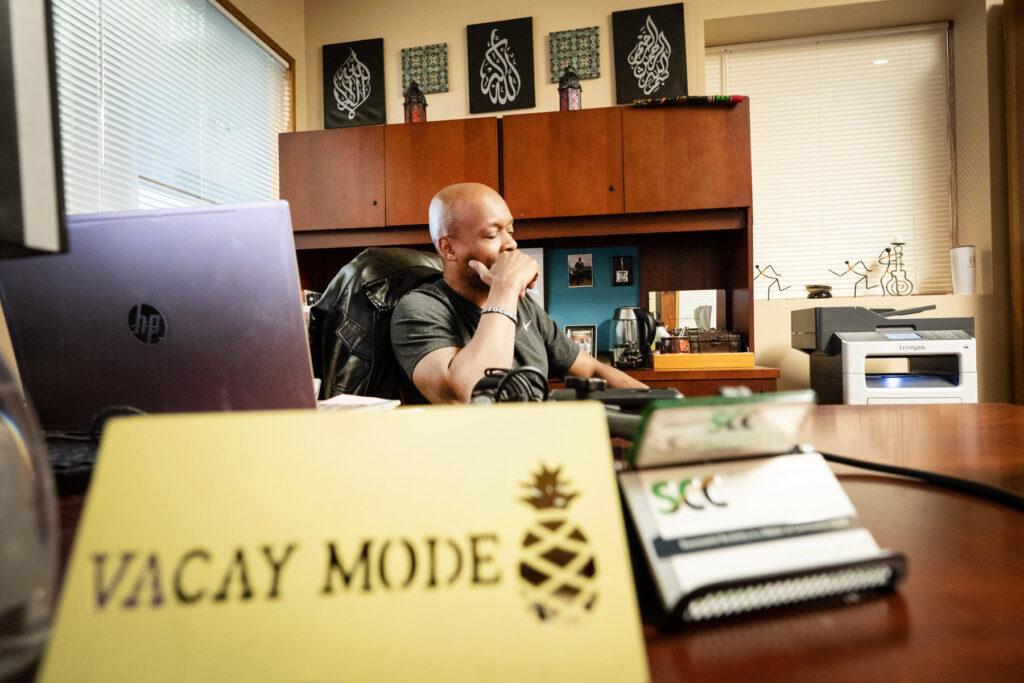

“The stories that happened are still notorious to this day,” said Arrington, now 55, and an office manager at the Second Chance Center in Aurora, a nonprofit that helps formerly incarcerated people transition into society. “They had guards bringing in drugs at Limon. They had, I think about three kids, no lie, born out of [Limon] because of relationships between staff and inmates when I was there.

“It was the kind of stuff you see in movies,” he added. Working as a porter in the prison, Arrington said he mopped up blood off the floor every morning that came from fights between inmates.

He said exercise helped him channel his anger.

“When I used to work out, I used to work out about an average of six hours a day,” Arrington said. “I was wound tight.”

His case worker tried to get him mental help for his anger, but Arrington refused.

“I’m in here for a murder I didn’t commit, I don’t smoke, don’t drink, never did drugs a day in my life,” Arrington said. “As far as mental health is concerned, I’m supposed to be angry. I’m supposed to be pissed off every day. I said if I’m walking around here with a smile on my face under these circumstances, then you need to come send me to mental health.”

In a clemency petition video submitted by family to the governor’s office, his mother Roberta Harris pleaded for her son’s freedom.

“Not to have Abron in our lives, how can I describe it,” Harris said. “… Emptiness, like a piece of a puzzle, like a piece of your life is missing. He was a happy, funny little kid. You know, joking all the time, you know, just full of laughter, just full of fun. He never had no trouble, no trouble at all.”

Mia spoke of her family experiencing inequities because they couldn’t afford a private attorney.

She said on the day her brother was officially sentenced in 1991, their family wasn’t notified to return to the courtroom to hear the verdict. By the time they made it back to court, Arrington had already been given a life sentence and whisked away in handcuffs, Mia, 56, said.

She said the justice system failed not only her brother, but their entire family. She recalled an unforgettable look in her mother’s eye the day he was sentenced — a look that was all too familiar and one she said she’s seen in the eyes of other women who have lost their children to police violence or to the justice system.

“They have to get better at what they do,” she added. “You know what I'm saying? Because we're dealing with human beings. Human beings and their lives and not just their lives, but their family's lives too.”

She quickly took on the role of being an emotional support for her family after Arrington’s incarceration. They felt helpless, she said.

“I wanted to fight but I couldn't,” she said. “You can't fight. You have to mentally get your mind together on who to talk to, who to reach out to.”

According to Wanda Bertram from the Prison Policy Initiative, most people are not serving long sentences like Arrington did but the negative impact is the same.

“Just the experience of being incarcerated forces people to be saddled with things like criminal justice, debt, the cost of incarceration, all the costs that their families bear to keep in touch with them,” Bertram said.

Broader impacts of incarceration

According to a study by the Bell Policy Center in Denver, incarceration has a pronounced effect on employment and a family’s ability to provide for themselves. More than 60 percent of formerly incarcerated individuals nationwide are unemployed one year after being released, the institute found. And those who do find jobs take home 40 percent less pay annually.

Incarceration is highly disruptive for career prospects and can have a long-standing “scarring effect” on formerly incarcerated individuals and their employment prospects, which can seriously affect the purchasing and earning power of families. Several studies show by removing the primary earners from a household, mass incarceration increases the depth of poverty among poor families, the center found.

In Colorado, the recidivism rate is 50 percent, the policy center stated. These impacts have a ripple effect in communities, which some researchers call “durable inequality,” meaning residents cannot escape what might otherwise be short-term poverty, the Bell Policy Center reported.

“And the trauma that occurs is incalculable,” said Scott Wasserman, president of the Bell Policy Center. “We have to grapple with this.”

Wasserman said he believes the state’s correctional system attempts to act as a mental health system.

“There's just a broad acknowledgment that many of the people in our correctional system have huge behavioral and health issues, but we are trying to treat them in a correctional setting,” he said. “And that’s really messed up.”

Across the 19 state-run prisons in Colorado, re-entry programs serve as a gradual process that begins when a person is incarcerated, according to Annie Skinner, a spokeswoman for the Colorado Department of Corrections. She said the department’s goal is to ensure inmates can live a quality life while incarcerated and to help them be prepared to enter society.

“Whether that purpose is that maybe they're gonna be in for life, but they can still have purpose behind that wall, whether that's a job, whether that's being a mental health peer assistant, and getting training on how to do something like that, whether that's participating in the innate radio station or the podcast team or education programs,” Skinner said.

“There's a lot of opportunities as well for folks that have life sentences to still do something that has good purpose behind the walls, even if it's not gonna be for them working towards release.”

An anxious release

On Feb. 27, 2020, Arrington walked outside from the Colorado Territorial Correctional Facility in Cañon City, which is where he spent the last of his incarcerated days. He pushed a cart in front of him containing his belongings.

For the first time in 30 years, he was a free man.

“I felt like one of those animals you see on one of those nature shows when they're releasing them, when they take the cage out and they open the door, literally that's how I felt,” Arrington said. “I'm pushing this cart and the guard, he was like, ‘You're good Mr. Arrington. Hey, good luck. Keep going.’”

He walked slowly toward the gate that would ultimately secure his freedom on the other side.

“I'm like, is this guy going to shoot me or something,” Arrington said through a laugh. “But the guard tells me, ‘just go.’ So I just pushed the cart through the parking lot and my sister and my brother was waiting for me.”

His sister Mia bought him some skinny-leg jeans, as fashion trends had changed a lot during the 30 years Arrington was imprisoned.

“His friends in jail were like, yo, somebody gonna have you in skinny jeans,” she said with a smile. “He's like, ‘no, nobody gonna have me in no skinny jeans.’ And I had skinny jeans for him when he got out."

“Once he got out of those, he went to go buy his own clothes after that.”

In a clemency letter to Arrington, Polis commended him for his commitment to bettering himself. He said there were several reasons he believed Arrington deserved clemency.

“At the time of your crime, you were 22-years-old,” Polis’ letter reads. “After a jury trial you were sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole. Though you did not commit the murder yourself, you received a sentence for first-degree murder — the same as if you had been the killer. Your three co-defendants, including the shooter and the gun owner, received lesser terms of imprisonment and they have now completed their sentences.”

Arrington was among eight people who received clemency by Gov. Jared Polis in 2019. Last year, 18 people in the state were granted clemency by the governor’s office.

While incarcerated, Arrington became a devout Muslim and garnered much respect from staff and his peers. He studied physics and engineering, and patented a flood mitigation system after becoming passionate about finding a solution to a flood he saw on television one day. His invention won first place in Breakthrough’s competition, where prisoners pitch and develop business plans for their projects. The organization was previously known as Defy Colorado.

During his time in the state DOC, he met and became close friends with Hassan Latif who was serving time too. Latif was released years before Arrington, and founded the nonprofit re-entry program the Second Chance Center in 2012. Arrington had a job at the center waiting for him when he was finally released, and he now helps others with successful reentry from prison.

Arrington said incarcerated individuals have much to offer society.

“A lot of these people literally contribute great things to society in communities if you just give them the chance to come back into the communities,” he said. “And there are a lot of them that are still locked up right now that really shouldn't be.”