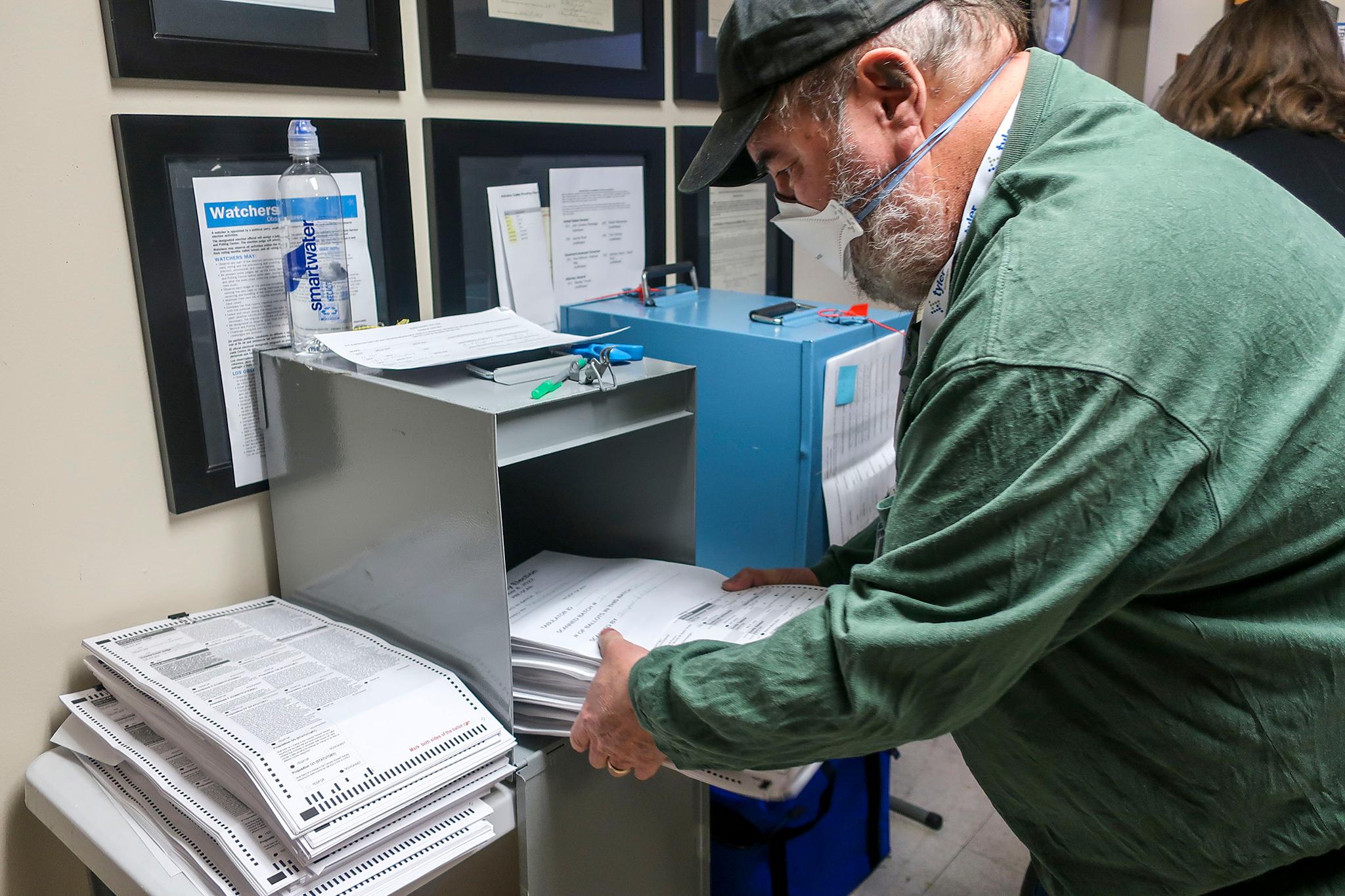

Lawful votes are unconstitutionally discarded in Colorado, often because a voter’s signature doesn’t match what’s on file, according to a lawsuit filed in Denver District Court late last week.

The signature match requirement is meant to prevent voter fraud, since mail or at-home voting takes place away from a polling site. But, the lawsuit said, fraud is extremely rare, and ballot rejections disproportionately impact diverse communities, disabled people and the youngest and oldest voters.

“For the vast majority of Colorado voters who vote by mail this fundamental right is contingent on an arbitrary, deeply flawed signature matching process,” read the lawsuit. “While ostensibly deployed to verify voter identity, signature matching is election integrity theater: it disenfranchises qualified voters by the tens of thousands, all for the appearance — but not the reality — of election integrity.”

The lawsuit notes that actual voter fraud is exceedingly rare.

A spokesperson for Secretary of State Jena Griswold released a statement: “The Department of State is currently reviewing the lawsuit and will defend Colorado law requiring mail ballot envelopes to be signed. Colorado ensures the constitutional right to cast a ballot, including by giving voters 8 days after an election to fix any signature discrepancy.”

Election judges, according to the lawsuit, are provided little guidance from the state on signature standards, and “are not handwriting experts and are not recruited based on any experience they have in validating signatures. They are required to take only a single election judge class prior to each election.”

Plaintiffs include Vet Voice Foundation, which seeks to mobilize military veterans to vote; Randy Eichner; and Amanda Ireton, represented by Perkins Coie attorneys based in Seattle. They filed a similar lawsuit in Washington state last month. Eight states and the District of Columbia have full Vote-at-Home systems, and most require signature verification, according to The National Vote at Home Institute.

Eichner is a resident of Larimer County, and has amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which severely limits his ability to control muscle movements. With the assistance of his mother, he voted in the 2022 primary election, but the signature was rejected.

“Although Mr. Eichner attempted to cure his primary election ballot, he was unable to do so because, as a result of his mobility limitation, he had allowed his driver’s license (the only form of state identification in his possession at the time) to expire. Because Mr. Eichner could not cure the perceived signature discrepancy, his ballot was not counted,” according to the lawsuit.

Matt Crane, the executive director of the Colorado County Clerks Association, said they are always trying to refine the system, especially for disabled voters. But he took issue with the lawsuit’s arguments.

“I don’t think they understand how our signature verification works,” said Crane, who noted a ballot isn’t rejected for signature mismatch on the envelope unless it first goes through multiple checks, and then a bipartisan team of judges has to sign off on the rejection.

Crane said dumping signature verification just because fraud is rare misses the point. “Part of the reason fraud is so low is because we have eligibility checks.”

A 2020 CPR News investigation found that more than 100,000 ballots were rejected between 2016-2020 because of signature issues

While Colorado’s voting system is regularly touted as the gold standard, a CPR News investigation found that between 2016 and October 2020, more than 100,000 ballots were rejected by county clerks, most often because signatures on the envelope didn’t match those on file. Colorado offers convenient ways to “cure” the issue, but many voters do not complete the process.

While the numbers of rejected ballots are very small relative to the millions of votes cast, some races still come down to just hundreds of votes, like in the third congressional district race earlier this month, where Republican Lauren Boebert won the race by less than 1,000 votes over Democrat Adam Frisch. Campaigns often work to get ballots cured for votes they believe are favorable for them in a close election.

Still, CPR News contacted voters who had no idea that their vote had been rejected. And research in other states has found a link between high rates of mail ballot signature rejection among communities of color. Instructions to cure ballots were only printed in English, in most Colorado counties.

The lawsuit calls out that disproportionate impact in Colorado: “in the 2020 general election, young Black and Hispanic voters’ ballots were rejected for purported signature mismatches approximately 25 times more often than were ballots from older White voters.”

CPR News also found that young voters were at particularly high risk of rejected ballots for signature mismatch, in part because their signatures tend to shift as they reach adulthood.

Whether voters with mismatched signatures are getting promptly notified of the error is another question

One of the plaintiffs, Amanda Ireton, 26, attempted to vote in Denver in the 2020 general election. Her ballot was rejected because of a signature mismatch. She doesn’t recall getting a notice that it was rejected.

“Although Ms. Ireton acknowledges that her signatures may have some natural variations because she often signs things quickly,” reads the lawsuit. “She does not know why someone may have perceived her signature to be non-matching in this instance, particularly because she had registered to vote shortly before casting her ballot.”

Nearly half of Colorado voters are not signed up for the ballot tracking system, and may not get a timely notice that their vote was rejected, according to the lawsuit:

“For example, one Colorado voter reported in 2016 that her general election ballot was wrongly flagged for a signature mismatch, and she was not informed until a campaign volunteer knocked on her door almost a week after Election Day.”

And Colorado’s eight-day post-election deadline for curing signature mismatch is “significantly shorter” than Washington, 21 days, and Oregon, 14 days.

In short, the lawsuit asks for injunctive relief, claiming that the risks of uncounted votes vastly outweigh the risk of fraud: “Signature verification offers paltry security benefits at enormous costs to voters in part because signatures can and do vary for many reasons.”

The case has been assigned to Judge J. Eric Elliff, and a review is scheduled two months from now, on Feb. 8.