Denver’s controversial decade-long embrace of school choice and accountability led to some of the largest academic improvements in education research history, according to a University of Colorado Denver study.

The authors of the study argue that the results imply it is possible to improve public education on a large scale using the reform strategy adopted by Colorado’s largest district from 2008 to 2019 — a strategy they say relied on school choice and competition, closing low-performing schools, empowering educators, and holding everyone accountable for test results.

“Did the reforms launched by Denver Public Schools improve student achievement district-wide, for the average DPS student? The answer is unequivocally yes,” said Parker Baxter, director of CU Denver’s Center for Education Policy analysis.

The study was funded by Arnold Ventures, which invests in evidence-based research and solutions in the areas of criminal justice, education, health and public finance.

It shows that DPS, despite having a larger population with much higher needs than other districts, improved at a much faster rate than other large districts and other low-performing districts in Colorado.

High school graduation rates went up 14 percentage points, and between 2008 and 2019, DPS students received about 1 to 1.5 years of additional schooling compared to students at other large and low-performing districts.

“These results are so large that it is hard to not be surprised by them,” Baxter said. “We simply do not have examples of educational interventions that have achieved this level of impact.”

Other cities — Los Angeles, Hartford, Connecticut, and Indianapolis, among others — have tried elements of the “portfolio strategy,” but none, other than perhaps New Orleans, was as comprehensive and long-lasting as Denver’s strategy.

What did DPS’s reform strategy entail?

In the traditional school district model, students are assigned to schools based on where they live. The system is organized in a centralized way, and teachers are paid on a standardized scale.

The DPS strategy prioritized school choice, empowering educators and accountability for outcomes, according to the researchers.

What does that mean?

How schools were governed changed. Today more than half the schools in Denver are district-authorized charter schools or innovation schools, which have greater control over time, budgets, hiring, and can waive elements of the teacher’s union contracts.

“It was the first time in American history that an elected school board voluntarily relinquished the authority to operate schools within its boundaries without giving up the authority to govern all of them under the district structure,” said Baxter.

During the study period, the district opened 65 new schools, and closed, replaced, and restarted 35 others. DPS developed its own school performance framework — a report card of the school's academic growth and achievement. School performance, largely based on test scores, was evaluated annually. Low-performing schools were closed. New schools were opened or restarted with new partners, or “turned around” which meant additional support and hiring new teachers.

DPS developed a “pay-for-performance” system, meant to reward good teachers with extra pay. It developed a teacher leadership model that allows exemplary teachers to coach and grow other teachers in their schools. DPS developed its own teacher evaluation system called LEAP that is aimed at recruiting, evaluating, and retaining strong classroom teachers. It set clear performance expectations and accountability for teachers.

The system relied on a single, common application for families to apply to any school in the district, and student-based budgeting, where some funding was allocated based on student need.

What were DPS schools like before these reforms started in 2008-2009?

In 2007, a fourth of school-age children in Denver didn’t attend the city’s public schools. Among white students, a quarter were going to private schools, according to an analysis by the Rocky Mountain News and the nonprofit Piton Foundation. The district had 31,000 empty seats with a capacity for 98,000.

DPS’s then-superintendent Michael Bennet, desperate to draw students back to the district, began ramping up the speed of reforms, in what the CU Denver report called one of the nation’s most comprehensive efforts to restructure how education was delivered.

In 2008, DPS was among the bottom 10 districts for scores on math and English state tests — that’s the 5th percentile. The graduation rate was 43 percent in 2008.

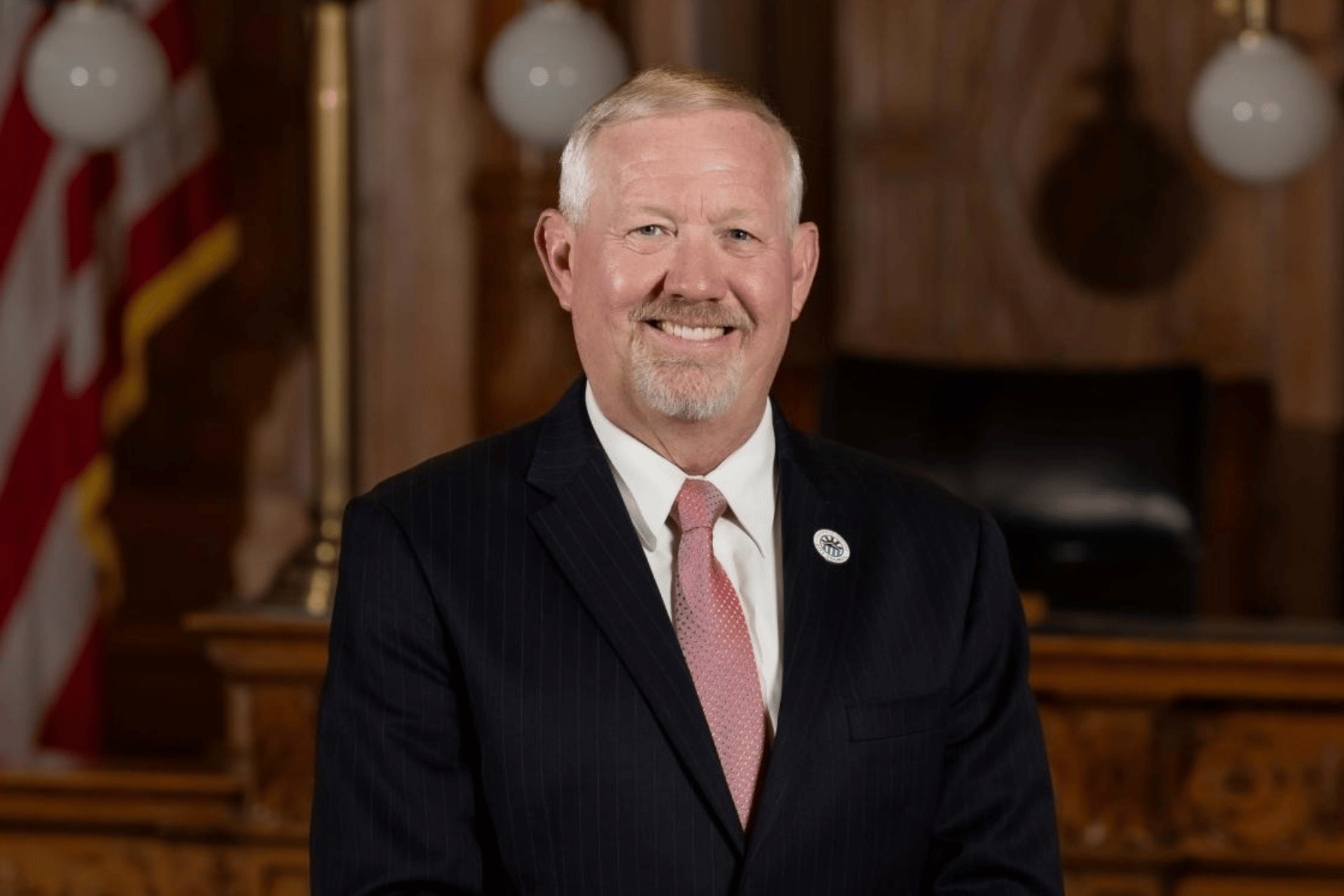

When Tom Boasberg took over as superintendent in 2009, he catapulted Denver into the national spotlight as the district that embraced school choice and autonomy, with an intense focus on raising standardized test scores. The transformation of the district was seen as a moral imperative.

What did the study find 11 years later?

By 2018-19, the study shows DPS had risen from the 5th percentile to the 60th among districts in English and the 63rd percentile of districts in math.

The study calculates that students enrolled in DPS during the 11 years of reforms received at least nine months and as much as 14 months of additional schooling than students in comparable Colorado districts.

Graduation rates also increased by 14.6 percentage points over the period. The four-year high school graduation rate climbed from 43 percent in 2008 to 71 percent in 2019. The study estimates if things had stayed the same without reforms, the graduation rate would have remained below 60 percent.

All demographic groups, Black, white, Hispanic, Asian Pacific Islander, English learners and special education students, saw improvements. However, because Denver’s minority populations are so large compared to other districts, statistically, the study couldn’t tie sub-group results specifically to the reforms.

But there was consistent improvement over the 11 years in terms of poverty, race and English language learner status.

“These reforms caused improvement among precisely the population that our society often assumes is not capable of success,” said Baxter. “Currently Denver is performing at approximately the state average and that is remarkable considering the needs of Denver students.”

Seventy-five percent of DPS students are students of color and more than 60 percent qualified for free or reduced-price meals.

Because all demographic groups improved, it also means achievement gaps remain, “so it raises the question of what in fact would be necessary to close gaps?”

The authors say the way the study was conducted allowed them to determine whether gains were due to DPS reforms specifically or reflective of academic growth across the state due to other measures. The study asserts that the improvements were not due to changes in demographics (enrollment grew by 25 percent) or factors like gentrification.

The controversial reform strategy wasn’t without costs.

Many observers would describe the reform years as turbulent, marked by turmoil and turnover at the school level, disruptions and community pushback. Long-time neighborhood schools, pillars of the community, were closed abruptly. Principals were frequently moved. Sudden policy changes calling for charter schools to co-locate in district-run schools caused uproars.

The district was extremely divided, often simplistically, between those who were pro-charter schools and those who supported neighborhood schools and teachers’ unions.

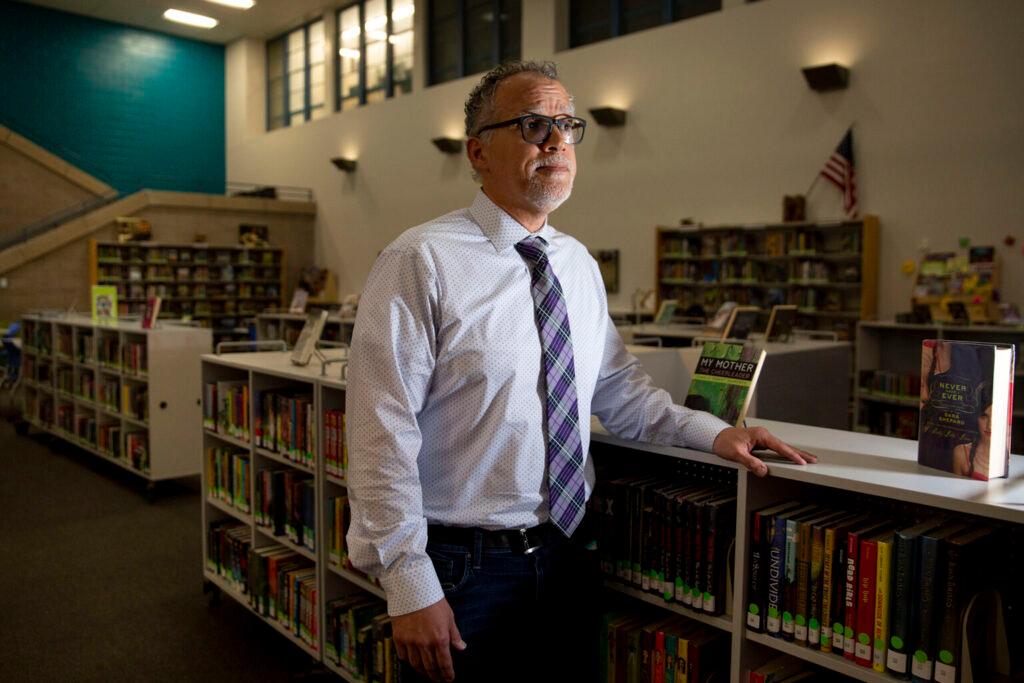

For several years at the end of the school year, a “do not rehire” policy left hundreds of educators blacklisted from working in the district. In some cases, those teachers’ students had performed above average or higher on state tests and were strongly supported by families. Many teachers complained that the intense focus on test scores and accountability stripped classrooms of freedom and creativity, and in some charter schools in the early years, ignored students’ cultural identities.

The teacher evaluation system became a work in progress, with pitched battles between the district and the teacher’s union over its implementation and fairness. Teachers resented being evaluated largely on a test score that students had no incentive to try on. They also became disenchanted with the pay-for-performance system that began in 2005, so much so that it became a major issue in a teacher’s strike.

“These results in no way indicate that these reforms benefited everyone,” said Baxter. “It is true that the reforms have harmed individual students, families, educators, but what this research shows is that although there are many people who experienced the reforms as a harm, many more benefited from them.”

While some educators perceived the reforms as an attack on the teaching profession, others jumped at the opportunity to start new innovation schools with more freedoms and fewer bureaucratic barriers. Many children in northeast Denver who previously had to bus hours a day to attend a school, now could walk or ride a bike to new schools in their neighborhoods, often charter or innovation schools. Thousands of students gained access to a school their parents believed better met their needs, giving many a chance to become the first in their families to attend college.

Despite the complexities and tradeoffs in ushering large-scale change, Baxter hopes the study’s facts help school district leaders.

“Those facts are not the only story, but they are most certainly a critical part of it that must be considered as we consider how to proceed in the future.”

DPS has rolled back some of the Boasberg-era reforms and is now grappling with the fallout of rapidly opening so many schools over the past decade just prior to major demographic decline in school-aged children.