Inside a nondescript suburban office building in a south Denver suburb, a woman named Alex Trebino stands on a blue balance board. Across from her is physical therapist Dan Stoot, who holds tennis balls in his hands.

“When you catch it with your right hand, I want you to tell me a musician,” he says, “when you catch it with your left hand, I want you to tell me a president.”

This is a brain game. He starts bouncing balls her way.

“Taylor Swift!” Trebino says with a quick giggle. “And George Washington.”

The first time Trebino tried this exercise, it was hard because for many months Trebino had suffered from a severe case of long COVID. It’s defined by the CDC as symptoms lasting three or more months after first contracting the virus, and that weren’t present prior to a COVID-19 infection.

“The first time we did this, there was not multiple hands with categories or multiple balls,” she said. “It was one ball at a time, and just throw it back.”

Trebino first caught COVID-19 early in the pandemic. She had fatigue, migraines and relentless brain fog, bad enough that she eventually resigned from her job as a management consultant. Then last year, a second bout of COVID set the 30-year-old Denver resident back even further.

“I had full-body tremors. I was shaking so bad. I couldn't walk, my spouse had to help me walk. I couldn't bathe myself,” she recalled. “I couldn't cook anymore. I couldn't do any household chores anymore. I was bedridden.”

“And I never got better. It's like, it knocked me down to a new baseline and that's just how I had to live my life,” Trebino said.

Doctors struggled to figure out how to treat Trebino, who said she has made progress through this type of physical therapy. And she’s part of a University of Denver study, one of countless efforts globally to understand and treat long COVID.

Long COVID is one big question

Even as that work ramps up, no one can say just how many Coloradans suffer from it.

“I think it's very large numbers,” said Dr. Sarah Jolley, a researcher with CU Anshutz and medical director of the UCHealth Post-COVID Clinic, one site of a national study looking at recovery after COVID.

The RECOVER study aims to understand how people recover from a COVID infection, and why some people do not fully recover and develop long COVID. With 17,000 subjects, including 300 recruited locally, “it’ll be definitely the largest observational study of recovery after COVID to date,” said Jolley.

The study will follow participants over four years. They’ll be followed continually to see how things are changing over that four-year period. They'll participate in surveys and then additional testing based on their ongoing symptoms, which will be tailored to those symptoms.

| How common is long COVID? |

|---|

| - Overall, 1 in 13 adults in the U.S. (7.5 percent) have “long COVID” symptoms, defined as symptoms lasting three or more months after first contracting the virus, and that they didn’t have prior to their COVID-19 infection. - Older adults are less likely to have long COVID than younger adults. Nearly three times as many adults ages 50-59 currently have long COVID than those age 80 and older. - Women are more likely than men to currently have long COVID (9.4 percent vs. 5.5 percent). - Nearly 9 percent of Hispanic adults currently have long COVID, higher than non-Hispanic White (7.5 percent) and Black (6.8 percent) adults, and over twice the percentage of non-Hispanic Asian adults (3.7 percent). |

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

Questions abound about the condition. Among them: How long will symptoms last? Once gone might they return? What treatments could work? Who is most susceptible? What can be done to prevent it in the first place? What determines if a case is mild versus moderate versus severe?

“I don't think we fully understand yet the science behind why some people get one extreme versus the other,” Jolley said.

Emerging research aims to help society cope with what some have called the next public health disaster.

“Thinking about how this is going to impact the workforce, how this is impacting patients, families, caregivers, all across the nation is incredibly important,” Jolley said.

National estimates for long COVID vary widely. One U.S. survey released in June found one in five who catch the virus develop long COVID; more than 40 percent of adults in the United States reported having COVID-19 in the past.

New research published last month raised additional concerns about risks from reinfection. A study published in the journal Nature suggested the risk of death, hospitalization and other serious health issues due to COVID-19 grew sharply with reinfection, compared with a first infection with the virus, regardless of vaccination status.

On its dashboard, the state has reported 1.7 million COVID-19 cases in total to date. That doesn’t include most home rapid tests. So potentially, “you're looking at half a million or more Coloradans that could be experiencing symptoms after COVID that are prolonged,” said Jolley, assistant professor of Pulmonary Sciences & Critical Care Medicine at the CU School of Medicine.

But no one seems to know for sure. Not health systems, and not the state, which is not compiling data on long COVID.

State epidemiologist Dr. Rachel Herlihy said it’s much more challenging to track than individual cases, identified by a positive test result. Plus, she said there is no universally agreed-upon definition of long-haul COVID.

“With long COVID, there's much more complexity in diagnosing it,” she said.

Colorado researchers zero in on brain

Once it’s diagnosed, how can patients be treated? Colorado researchers are zeroing in on one part of the puzzle: the brain.

At DU, Bradley Davidson directs the human dynamics lab, where they measure human movement and explore how people move and why.

When the pandemic hit, Davidson and his colleagues had an “ah-ha” moment. It seemed like a constellation of familiar long COVID symptoms, things related to sleep, fatigue, memory and emotions, resembled those of a high-profile kind of injury.

“We had that, ‘Whoa, this looks very similar to concussion,’” he said, defined as a traumatic brain injury that affects brain function.

Davidson and his team wondered if they could examine how motor control, motor skills and movement are affected by COVID-19. And maybe they could find promising ways to help patients.

“So if having COVID and now having long COVID is like having a chronic brain injury,” Davidson said, they then hypothesized, “we could treat long COVID the same way that we treat post-concussive syndrome.”

That involves studying eye movement and tracking, along with head movement, which he says, traditionally could indicate a problem with the brain, which his team has found is treatable by rehabilitation therapy.

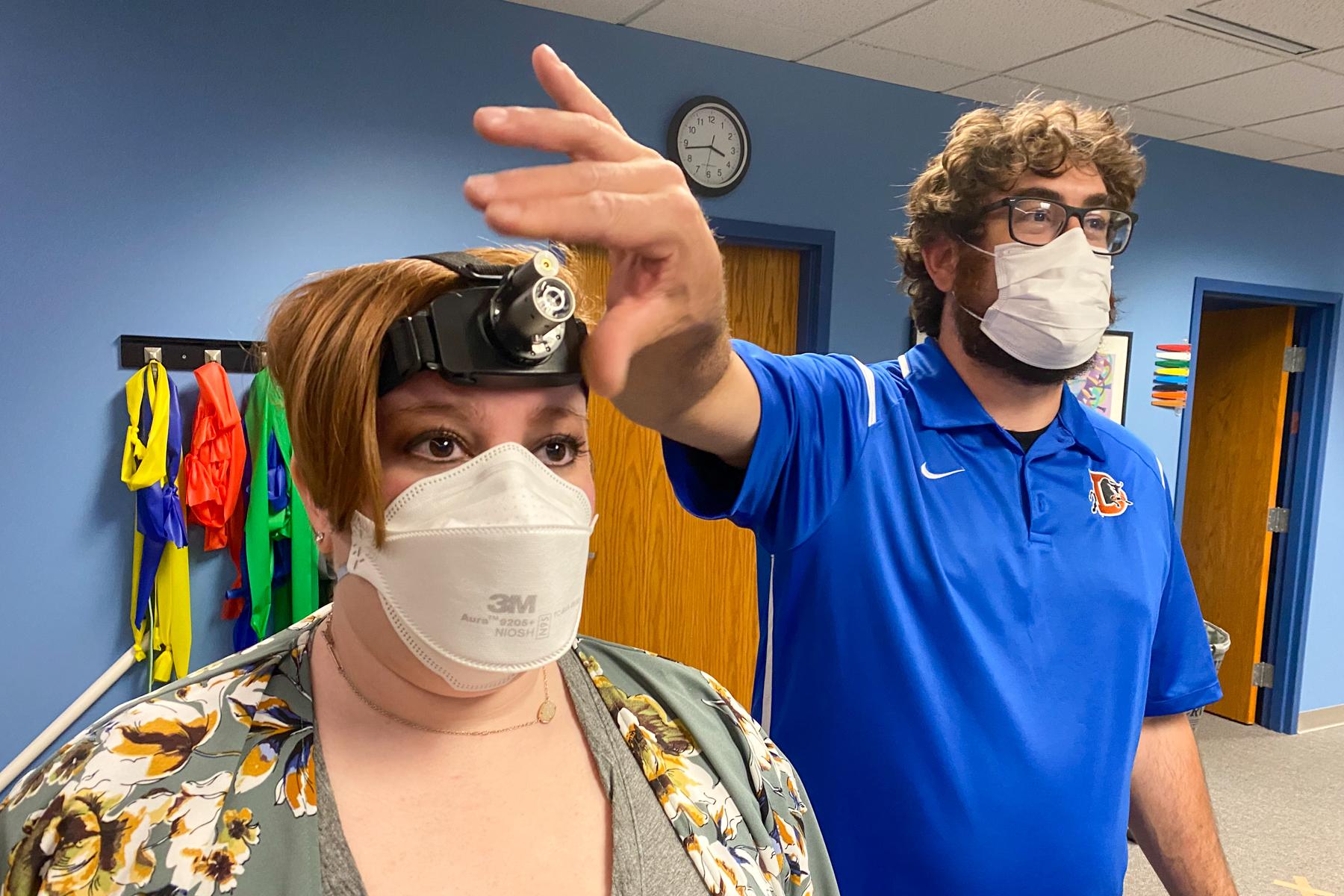

Back in the physical therapy clinic, Dan Stoot worked with Alex Trebino on another brain game, this time using a pair of handheld lasers and one on a headlamp to guide the light through an intestine-looking maze on the wall.

Trebino has worked on these sorts of brain games, involving things like balance, movement, memory and tracking objects with your eyes, for months now.

And she is seeing progress.

“It’s definitely gotten easier to do, I’ll say that,” Trebino said.

Stoot, the clinic director and owner of High Definition Physical Therapy, said so far their research shows some brain games seem to help. So he can tell patients: “There's actually some things you can be working on that should have good functional outcomes for you.”

That’s given hope to Trebino, who has yet to return to work and has submitted a federal disability application due to long COVID. She said that it was denied, and she has appealed.

But she said the work she’s doing in physical therapy is encouraging.

“I would say at my lowest, I was 5 percent on a good day. I'd say now I'm somewhere between 25 and 30 percent. So there's been dramatic improvements. There's still a long way to go.”

Others with long COVID learning to live with it

And there’s still a long way to go for many other Coloradans, like Ana Rodriguez, from Thornton, and Clarence Troutman of Denver. I met them on a cool, cloudy day in a park in northwest Denver.

They didn’t know each other before COVID-19 hit.

“Well, we bonded, I feel like we bonded just through our experiences,” Rodriguez said.

“We're in touch,” Troutman said. “Definitely, we're in touch.”

Both caught it and were sick enough to be hospitalized. They became friends through a support group after they were released. That’s helped them cope. Rodriguez said more than two years later her post-covid symptoms include fatigue, brain fog, depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

But the worst symptom is in her hands and feet.

“They feel like they're on fire,” said Rodriguez, a mom of three adult kids, describing neuropathy, a weakness, numbness or pain from nerve damage.

Clarence Troutman, of Denver, and Ana Rodriguez, from Thornton, have both struggled with physical changes brought on by long COVID. They became friends through a support group after they were released from the hospital after getting sick from COVID-19.

She says her skin can feel like it might burst.

“If you look at them, my hands aren't swollen, but they feel so swollen that they hurt,” she said.

So far, she hasn’t found any satisfying treatment for that pain.

For Troutman, some physical therapy helped him deal with a shortness of breath and get back some stamina. But he still grapples with persistent brain fog and difficulty concentrating.

“I have a lot of trouble reading now, especially anything that's an article longer than maybe a paragraph,” said Troutman. He added he does some word games, like word search and crossword puzzles, “just to try to build back up,” those mental skills.

Troutman was a broadband technician with CenturyLink for 37 years. He caught the virus at the start of the pandemic, was hospitalized and on a ventilator for a time, and ended up staying two months.

More than two years later, the fight, both he and Rodriguez said, goes on. They hope future breakthroughs in research and treatment will bring some relief.

“Just to live with pain every day is a struggle,” said Rodriguez. “It's gotten better, but it's still there. So I have to learn how to deal with it. This is a new norm.”

For many long-haulers, they’re learning how to live with it, and hoping emerging studies could help others figure out how to avoid coming down with a case of long COVID, or how to treat it if they do.

“It's real. Once you're out of the hospital, it's not over,” Troutman said. “You're still dealing with a lot of things over a long period of time.”

And with the pandemic grinding on, the number of Coloradans coping with long-covid just keeps growing.