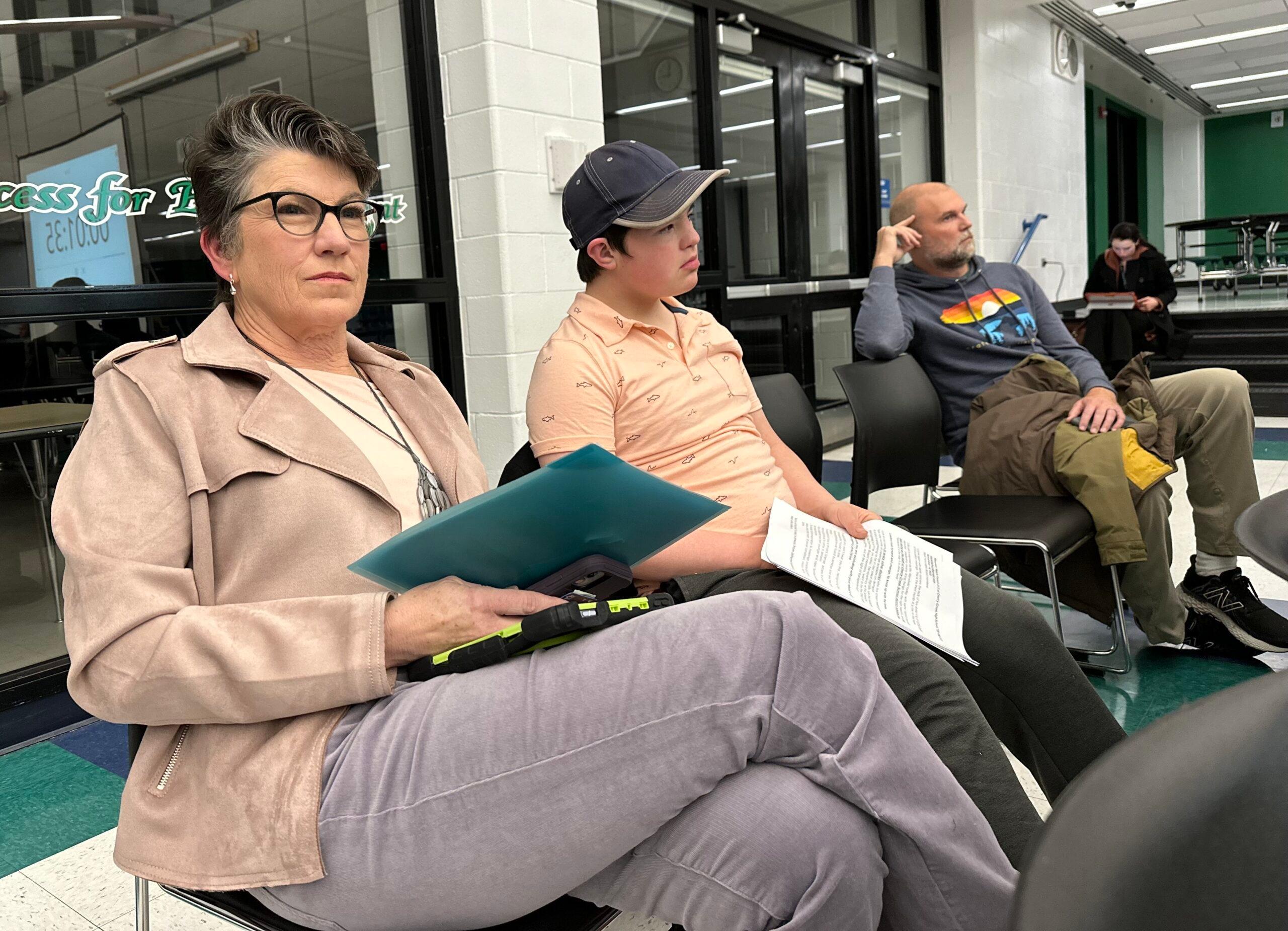

Maureen Welch has two children in Cherry Creek schools. As a former teacher, she likes to know what’s going on.

“I guess I'm kind of a meeting nerd. I like to go to a lot of meetings,” she laughed.

Rain or shine, she goes in person to the monthly school board meeting.

“I'm always interested in learning more about policy, curriculum, budgets.”

And not just the formal board meetings, she likes the study sessions. That’s where board members hash out policy. (Confession, I do too.)

“I'm always the only person from the public there, which is kind of interesting. I show up and I learn.”

Cherry Creek district holds its meetings at a different school every month. One Monday night, Welch realized she didn’t want to drive all the way across town to get to this particular meeting. She also has to find a sitter for one of her sons, who has a severe disability. So, she decided to watch it online.

“And then I was like, wait, they don't have it online,” she said. “This is crazy.”

Welch did some research. She discovered that Cherry Creek is the only major school district in Colorado that doesn’t live stream its school board meetings. Even many rural districts do.

Further, it didn’t post the audio on the district website, so people who couldn’t attend couldn’t listen or watch either. Most school districts post the video immediately after the meeting.

But many districts, including Cherry Creek, became experts at live-streaming meetings during the pandemic. They discovered teachers and parents like the convenience, not to mention the peace of live streaming because of the atmosphere in some board rooms. The vast majority of major districts, if they weren’t already streaming, decided to make it permanent — except Cherry Creek.

Colorado’s open meetings law doesn’t require school boards to live stream. The meeting just has to be open to the public. And the meeting has to be recorded, with no requirement to post it.

“But here we are in 2022, and one of the things we learned is we can use technology to bring government closer to the people,” said Jeff Roberts, executive director of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition, a watchdog for governmental transparency. “Why not continue providing that service to your community?”

Welch contacted Cherry Creek board members.

No answer. So, she spoke at a board meeting, challenging the board to open the process, “to make the tent bigger, to broadcast/live stream all of your public meetings.”

Welch came back the next month. No response. And the next month.

“I think it’s a bit of a travesty that only able-bodied, privileged people like myself who are able to get here are the ones who are able to listen to the meetings and speak to the board so I really urge the board in the name of equity to really consider this.”

Each time, she asks for the same thing.

“When a big district doesn’t do it, you wonder why not?” Roberts said.

The district declined an interview with CPR. But at a November school board meeting, board chair Kelly Bates explained that it’s been the tradition in the Cherry Creek district to hold meetings at schools in every area of the district. The board doesn’t have a permanent boardroom.

“We choose to go out into the community to meet families where they are,” Bates said. “This gives every family the opportunity to attend the meeting at a school that is close in proximity.”

The district argues that because it travels from school to school for its monthly meeting, it’s not able to live stream.

Welch doesn’t buy it.

“You know, 20 years ago that was great, and it was very cutting edge and revolutionary, but I think nowadays, people really would prefer to participate remotely,” she said.

There are a number of reasons people want new ways to access board meetings.

CPR reached out to parents and teachers in districts that have live streaming. They like it because it’s convenient and they don’t have time to wait three hours in person to give a two- or three-minute public comment.

“Weeknights are busy,” said parent Meg Furlow. “Getting home from work, dinner, after-school activities, and bedtime. Virtual meetings allow us to stay involved with what is going on. It makes elected officials more accessible and hopefully accountable to the public.”

Other parents can’t afford to go to meetings.

“It’s another way to temper privilege in our community,” said parent Tammy Overacker. “Some families simply cannot pay for a sitter for a school board meeting. Often these are our already marginalized groups. Giving the option to participate virtually allows for community-wide participation.”

Many of these districts, like Douglas County and Denver, even allow remote testimony during public comment. That’s a relief to some community members who find the rhetoric and emotions at some public comment sessions disturbing. It started over mask wearing and grew to other issues like learning about race in school.

The Douglas County School District director of security and safety sent a letter to community member and former county GOP officer Stephen Collier for exhibiting “threatening and intimidating behavior” at a board meeting last year. Video depicts him “aggressively” lunging toward another person in the audience, the letter stated.

“Everyone in the meeting plays an important part in modeling appropriate behavior and promoting an environment that is fair, safe and dignified,” the letter read. “At this time you are no longer permitted to attend future Board of Education meetings or forums in person.”

Some members of the public routinely attack school board members and district officials, who they’ve called “sociopaths, dictators and tyrants.”

One woman at Greeley Evans 6 school board meeting last week shouted at individual board members by name, calling them “disgusting” and claiming there’s a Satanic symbol in the district logo. Misinformation abounds, with another woman accusing the board of “letting porn and bestiality and incest and rape into our schools.”

Some audience members are disruptive. Board chair Michael Mathews eventually had to slam down his gavel and adjourn the meeting “because we have no sense of order from the participants.”

A month ago, the board even considered eliminating public comment, which is legal in the state.

“I feel for them not knowing what to do about that because they didn't used to have to deal with stuff like that. It’s awful. We have to find a way to do it civilly,” said Roberts of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition.

During District 49's school board meeting last week, a community member dressed as Santa performed a rap against teaching social-emotional learning (SEL), which enables teachers to weave into instruction skills like how to control emotions and how to be respectful to others.

But some parents mistakenly connect SEL to “CRT,” critical race theory, which is not taught in schools. Santa used the rap as a way to attack teachers.

"There are certain district teachers who will use that SEL, to indoctrinate our children into a living hell," she rapped.

It can be difficult for educators and parents or members of marginalized groups like LGBTQ to sit in a boardroom where they feel intimidated.

Members of a militia group showed up at a Cherry Creek board meeting last year. At a November meeting this year, the board room was packed — and divided. The district was giving an update on its equity policy. During public comment, an audience member filmed teachers who spoke in support of equity.

Shana Shaw first testified at a Cherry Creek School District board meeting back in the late 1980s when she was in middle school and the Ku Klux Klan was harassing Black students at her school.

Shaw, who runs a youth advocacy organization Compound of Compassion, testified in support of the district’s equity policy at the November meeting. She said as a Black woman in the U.S., she has had to adjust and endure in many hostile environments so testifying in person at the school board is no different. But it may be hard for others.

“You have a lot of DACA students who don’t want to ruffle any feathers for fear that their families would be attacked, they’re situations of people of color feeling intimidated and not feeling safe enough to allow their voice to be heard in a setting like that.”

Some teachers, parents and LGBTQ students say they’re uncomfortable speaking in person. One parent of a STEM school shooting survivor says she doesn’t feel safe going to DougCo board meetings in person, especially after comments made by the board president at a meeting on Dec. 13.

Board president Mike Peterson laid out the ground rules just before public comment period, stating that, “we’re going to do the First Amendment here.”

“We welcome all views here whether they’re controversial … we don’t fact check people up here whether they’re true or false. We’ve even had people wearing T-shirts that have accused board members of felonies. But we’re going to allow that because it’s the First Amendment and even hateful speech is protected.”

The comment about allowing hateful speech at a school board meeting is another reason many people say they feel safer listening and testifying from home.

Several months after Cherry Creek parent Maureen Welch began lobbying for live streaming and posting audio, the board president announced it would be making recordings of the meeting available to the public.

It’s a first step. But to Welch, it’s a far cry from live streaming and remote testimony. She’ll keep fighting that fight.

After listening to school board meetings for the past decade the most cogent, respectful, polite demographic group at school board meetings this reporter has witnessed are students. And that’s a ray of light.

“The students can set a good example for their parents,” Roberts said.