Coloradans will soon see missing person alerts on their phones, local television stations and social media platforms specifically about Indigenous people.

The Colorado Bureau of Investigation is launching its first-ever Missing Indigenous Person Alert system on Dec. 30. The goal is to help solve more crimes in a community that sees a disproportionately high rate of missing people and homicide cases when compared to other racial or ethnic groups.

The new tool will look and function similarly to Amber alerts for missing children, as well as other existing alert programs for missing adults and senior citizens. The alerts will broadcast through the same state-run distribution system from CBI at the request of local law enforcement agencies.

Colorado is the second state in the country, after Washington, to launch this type of alert at the direction of legislation passed earlier this year.

Proponents say the system will draw more attention to time-sensitive cases that have historically fallen through the cracks due to poor communication between tribal, local and state law enforcement. A lack of media attention to many cases also contributes to the problem.

“It just feels like we're always put on the back burner,” said Daisy Bluestar, a representative of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives Taskforce of Colorado and member of the Southern Ute tribe, who advocated in favor of the alert’s creation.

“In Indian country, we know each other all across the board,” she said. “If somebody goes missing in my community and we get a statewide alert out there, there’s a really high chance that everybody will kind of know which family they come from, which direction to look, where to send people.”

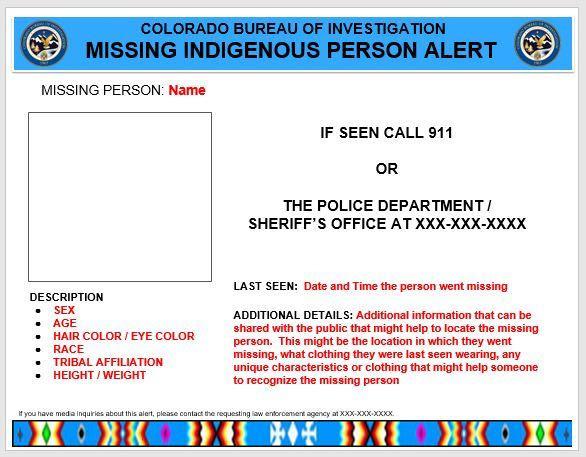

The alert bulletin will have a special title at the top and include identifying information about the missing person. The alert also features a traditional scroll design along the bottom border.

But the final structure of the system was adopted earlier this fall through a public hearing process.

How it works

The alert requires local law enforcement agencies in Colorado to notify CBI to request a statewide Missing Indigenous Person Alert within eight hours of a report of a missing adult or within two hours of a report of a missing child.

The bureau must then enter their case into a statewide database and independently confirm the missing person is “believed to be an Indigenous person or a member of a federally recognized tribe,” according to program rules.

After that, the bureau will enter information such as the missing person’s name, last known location and tribe affiliation into a special bulletin. It will then share that with media outlets in the state for publication, as well as other organizations within the Indigenous community that may want to share the alert.

That could include out-of-state law enforcement agencies or community organizations, said Audrey Simkins, an investigative analyst with the Colorado Department of Public Safety who oversees when alerts are issued.

“Some of our tribal communities are actually closer to an Albuquerque media outlet than they would be to the Denver outlet, for example,” Simkins said. “So we need to kind of think outside the box and make sure that we're reaching out to our partners who are in our neighboring states.”

Other outlets for the alerts could include digital highway billboards in Colorado or cell phone alerts to draw more public attention to the most serious missing person cases, Simkins said.

“It’s really one tool in the toolbox that highlights the need for community involvement,” she said.

A long time coming

Indigenous advocates fought hard for the creation of the program as part of a broader legislative package designed to devote more state funding to the issue. Some estimates put the murder rate in some of the country’s Indigenous communities as 10 times higher than the rate for other racial and ethnic groups.

The problem stems from a number of factors, including the nation’s treatment of Native communities throughout history and high rates of domestic violence. Women are particularly at risk.

The Colorado bill, which got some pushback from the Polis administration, also created a new state office with a half-a-million-dollar budget dedicated to solving more of the Indigenous community’s cold cases.

The office recently hired its first-ever director and is rolling out sensitivity training programs for law enforcement across the state, among other efforts.

“It’s important that we take every step we can to bring some resolution to these cases,” said Arron Julian, director of Colorado’s Office of Liaison for Missing or Murdered Indigenous Relatives.

“This was a grassroots idea brought up by the Native community and advocates,” Julian said. “(The alert) is a great idea to bring awareness to the whole state of Colorado.”

Native advocates have also requested more input into the state’s efforts. During the public rulemaking this fall, advocates pushed for the alert to be named after Marie Ann Blee, a 15-year-old Ojibwe girl who went missing from Craig in 1979.

The name hasn’t been adopted. But a spokeswoman for CBI said officials are aware of the suggestion, and a discussion on a specific name will likely take place at a later date.

“I’m happy the alert’s coming out regardless,” said Raven Payment, a member of a grassroots MMIR task force that shared public comments about the new system.

It’s unclear how often the new system will get activated. So far in 2022, CBI issued 4 Amber alerts and 27 Endangered Missing Person alerts for the general population, which is on par with recent years.

Comprehensive data on the number of missing or murdered Indigenous people in Colorado isn’t widely available. But at least six missing person cases in Colorado this year — including an Ignacio woman who was murdered in November — could have benefited from the new Indigenous-focused alert, Payment said.

“We lost time in the search for her not having an alert system in place,” she said. “We’re a small community. We recognize names. And this will speed things up.”

Promising results in Washington

The system in Washington state resulted in more than two dozen resolved missing person’s cases in roughly six months, according to local law enforcement.

“It’s been extremely effective because you can’t find someone unless you know they are missing,” said Patti Gosch, a tribal liaison with the Washington State Patrol, which operates the system.

Washington’s alert runs similarly to how Colorado’s will — with local law enforcement requesting the state’s help in cases. State Patrol agents have found the streamlined request process cuts down the time it takes to issue a statewide alert by roughly 12 hours.

“Before we would have to call and contact everyone ourselves and hinge between all these different groups to get information,” Gosch said. “It wasn’t a straight line.”

The patrol instead blasts out Amber-style alerts with specific missing Indigenous person language to phones in a specific geographic area. Residents can also subscribe to receive all alerts directly by text or email.

An updated list of all missing Indigenous people is now published online every other week as a part of the program, too, said Gosch.

“That’s finding people, too, because sometimes a community member may not know that they’re missing,” she said.

Colorado’s first test of the system will likely come after the New Year, once the latest rules go into effect on Dec. 30. Advocates and families in the state’s Indigenous communities are hopeful it makes a difference, said Bluestar, the Southern Ute resident and advocate.

“I think there's a good history of people just forgetting who we as Native people are,” Bluestar said. “But we’re not going to be silenced or forgotten anymore.”