Joslynn Lee first discovered science as a little girl growing up on the Navajo Nation. Her nalí, her grandma, would point out the different plants as they herded goats. Lee remembers that knowledge getting her curious, excited to learn more. She would eventually fall in love with chemistry. She now teaches it at Fort Lewis College, which sits high on a hill above Durango, a small city in the Rocky Mountains.

When she hears her lab students teasing each other in Diné, her native language, she encourages it.

Lee wants to “welcome that that's a safe space for them to be able to use some of their vocabulary from their own Indigenous language to then be able to be themselves in lab,” she said.

When Lee was at the same school in the mid 2000s, she never was able to experience that kind of camaraderie in her science classes. There just weren’t many fellow Native students in them. But Indigenous enrollment has been increasing at Fort Lewis. At the same time, the country has been going through a reckoning of how it used education as a weapon against Native people.

The federal government is in the middle of an investigation into the more than 400 Native American boarding schools that operated in the U.S. for a century and a half. Many students were sent to them against the will of their families as part of the government's policy of assimilating Native people into white culture.

Unmarked graves have been found at more than 50 schools. Historians have called it “cultural genocide.”

Now, at some institutions like Fort Lewis, there’s a push to confront this violent past — and take back education for Native people. Fort Lewis actually operated as an Indian boarding school from 1891 to 1910. It was later a high school and a two-year-college before becoming a four-year college in the 1960s. Since 1911, Colorado has been offering Native people free tuition at Fort Lewis as part of an agreement with the federal government — which had forced Native people from these lands.

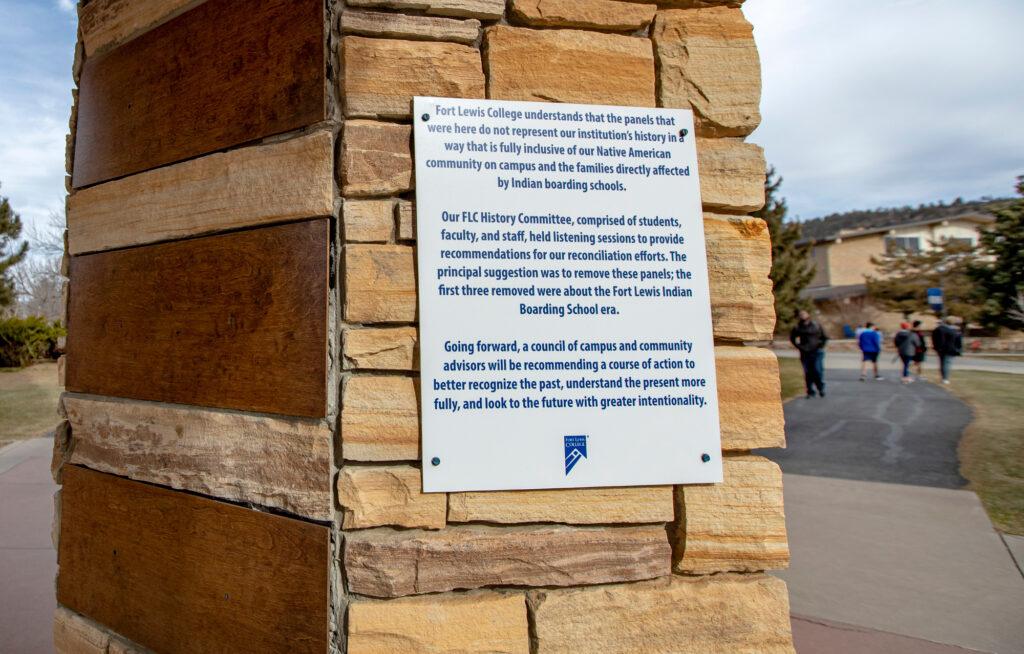

For years, this history was whitewashed on historical markers on a clocktower in the heart of campus. The markers described the boarding school as a place where Native people “developed excellent skills.”

Lee remembers walking past the inscriptions as an undergraduate here. When she returned to become the chemistry department’s first Native professor, she was shocked they were still up.

“I was thinking of how I would feel as a student seeing these images and what they depicted,” she said, “and yeah, I don't want another student to see that.”

The administration ultimately agreed. After Lee wrote the college’s president and the school held more than a year of listening sessions, the markers were removed.

The history of Native American boarding schools still hangs over the U.S. education system, however. Fort Lewis’ Majel Boxer says one of her grandfathers actually escaped from one of those schools in Montana.

“Just as a family, we're proud of him,” she said with a laugh. “You know, we're glad that he had that spirit, that he didn't want to stay at boarding school. And so he left.”

But Boxer, an associate professor of Native American and Indigenous Studies, knows most Native children were not that lucky. She said all her Native students are likely descendants of boarding school survivors. In order for them to succeed, Boxer explained, they need to feel comfortable bringing their whole selves to college, “where they don't feel like they have to live in two worlds the way former boarding school students had to do.”

For Boxer, an enrolled citizen of the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes, teaching helped inspire her to start sewing traditional ribbon skirts, with layers of colorful ribbons stretching around them. She wears one every day to class.

“I do think that that matters, and it helps our students be more comfortable,” she said. “If a professor's wearing her ribbon skirt as part of her daily wear, then why couldn't they?”

She’s happy to see more students wearing their ribbons skirts on campus.

While almost half of Fort Lewis’ undergrads are Indigenous, only about six percent of the faculty are. But Boxer explained that they’re working to indigenize instruction, from drawing on their students’ own Native knowledge to allowing them more absences to go home for ceremonies and family matters.

“Today, as contemporary Native peoples, we need to see education not through that adversarial lens, but to see education as a tool, and the tool is for our own goals,” she said.

And many Native students at Fort Lewis have the same goal: to return home to help their community.

In the school’s parking lot, Justin Dash was twirling a lasso around him, the rope slapping the ground in the figure-eight pattern. Over and over, he practiced roping a plastic, bright orange steer, smiling when he got it right.

Dash, who says he learned to ride a horse before he could walk, started the school’s rodeo club. He’s studying to be a physical therapist and dreams of returning to his hometown on the Navajo reservation, Tuba City, Arizona.

“Recently, we had our Navajo Nation Fair and there [were] only two EMTs parked there,” he said, describing “lots of injuries” from the bullriding. “So I'd love to go back and help with all of that.”

He thinks money is one of the biggest things keeping Indigenous people from a degree.

He saw people grow up “in shacks, sheds, broken down trailers.” Some of his friends who did make it to college had to drop out to help their families. Dash thinks that maybe more scholarships will help dismantle the mentality he felt surrounded by growing up: that just because you grew up poor, without family who went to college, you’d have to stay that way.

A first-generation college student, Dash smiled as he described how his father helped motivate him to get good grades and go far in his education. One day Dash was helping his dad, a traveling welder, work in the hot Arizona sun.

“And he said, ‘Do you really want to be doing this for the rest of your life?’”

Dash remembers replying with a “no.” He feels blessed that his family can help pay his way through school.

But many young Native people don’t have that support. That’s what Byron Tsabetsaye sees as the director of the Fort Lewis’ Student Involvement Center. In addition to Fort Lewis, a growing number of universities now give free tuition to Native students, but Tsabetsaye knows that’s only part of the equation.

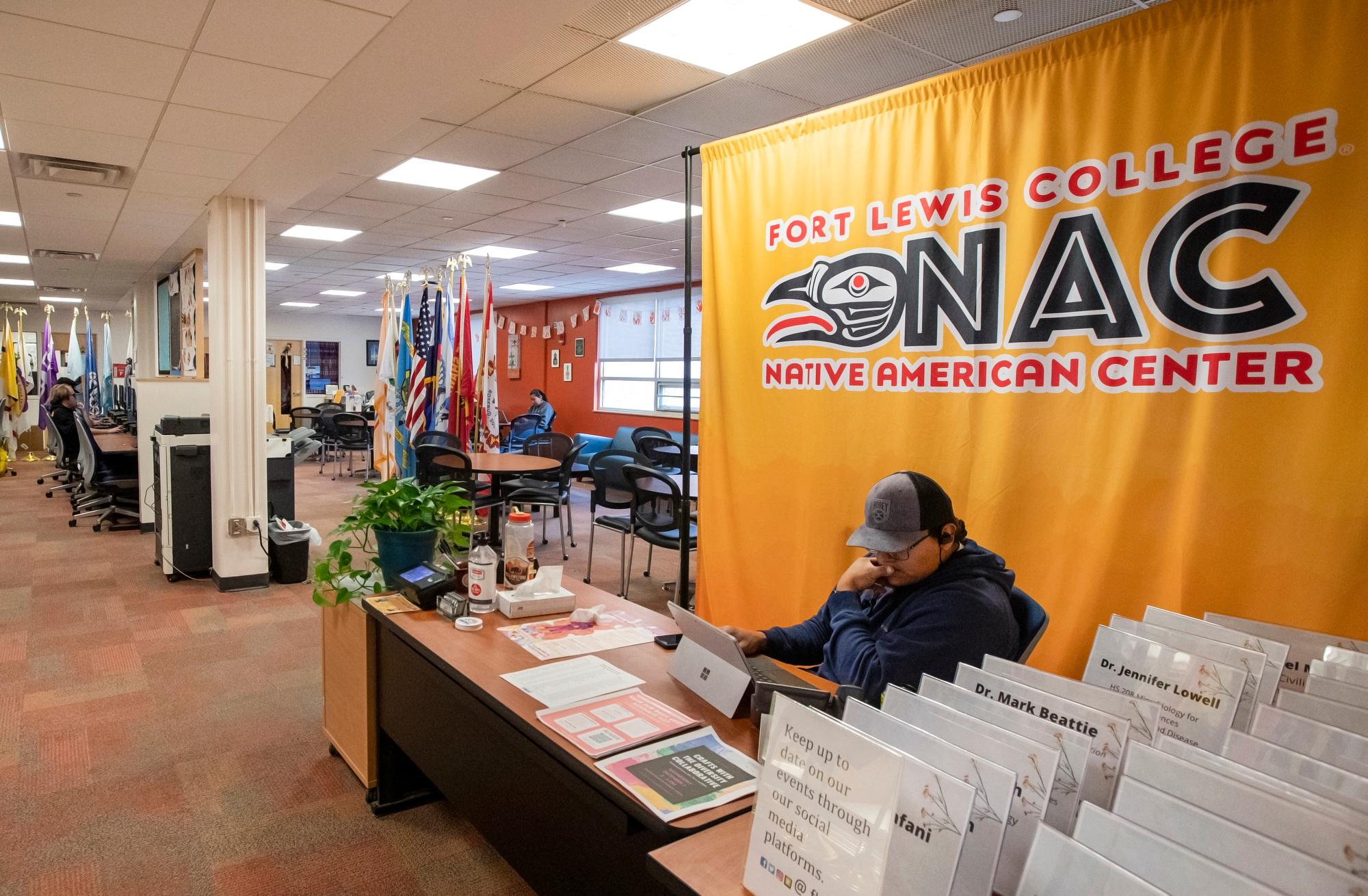

“To offer a Native American tuition waiver, that's one thing,” he said. “To provide the cultural sustenance that Indigenous students need in higher education, in college, is another thing.”

The first in his family to graduate college, he didn’t feel prepared to continue school growing up on the Navajo Nation and applied to Fort Lewis on a whim. Tsabetsaye thinks universities need to reach out more to prospective Native students — and that once they’re on campus, they need to be supported and embraced for who they are.

“If you’re going to make a commitment to serving Indigenous students, it doesn’t stop at enrollment,” he said.

It also takes acknowledging the painful past at places like the Fort Lewis Indian School, which eventually grew into Fort Lewis College. Its original buildings still stand on about 6,000 lonely acres outside of Durango. In warmer months, classes are held there and produce is harvested. Cows roam the site year-round.

As Heather Shotton, Fort Lewis’ new vice president of diversity affairs, stepped onto the snowy grounds, she felt sadness for what happened here. But not just that.

“With many of our programs and with our college today, I feel a sense of hope in the reclamation that I see happening,” she said.

It’s the reclamation of an educational system that once tried to erase the identity of an entire people, including Shotton’s people. She’s a citizen of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes and a Kiowa and Cheyenne descendant.

Her aunts, uncle and grandparents were boarding school survivors.

“I think about them all the time,” she said, her voice breaking just a bit.

They give her strength as she works within higher education to heal the past and look toward the future — a process that she says may never be finished.