Bill after bill, hour after hour, a small group of public servants huddle together in a nondescript bunker just north of downtown Denver to sort through thousands of dollars in cash.

These are the foot soldiers of the Regional Transportation District’s treasury, who sift and count every nickel that passengers feed into train ticket machines and toss into bus fare boxes.

“Typically, it could be anywhere from $4,000 to $12,000 in coin [in a day],” said Gene Byron, RTD’s treasury supervisor.

That’s on top of $30,000 to $60,000 in bills that transit passengers deposit each day. The cash, most of which comes from bus customers, totaled roughly $12 million of the nearly $80 million in fares RTD collected in 2021.

RTD’s fares have been in the spotlight in recent months. The state government sponsored free transit rides across Colorado in August to boost ridership. And some on RTD’s board of directors have questioned whether it’s worth it to continue collecting them.

“I'm curious as to how much it costs us to actually collect those fares?” board member Bob Broom asked at a September meeting. “[Do costs] eat up half of that fare revenue that we get?”

Perhaps, Broom suggested, RTD would be better off offering free rides and seeking new funding to offset the cost.

“When the state looks at ways of cutting greenhouse gasses, this may be one of the most cost-effective ways for them to do it … to pay RTD to haul people around free,” he said.

While we now know that the August free fare experiment led to a significant bump in transit ridership, RTD’s final report did not quantify its impact on air quality or climate emissions. And RTD staff also couldn’t tell Broom and other board members another key data point: just how much it costs to process fares.

So CPR News asked RTD to run the numbers.

Read on for RTD’s analysis. But first, let’s get back to the cash room

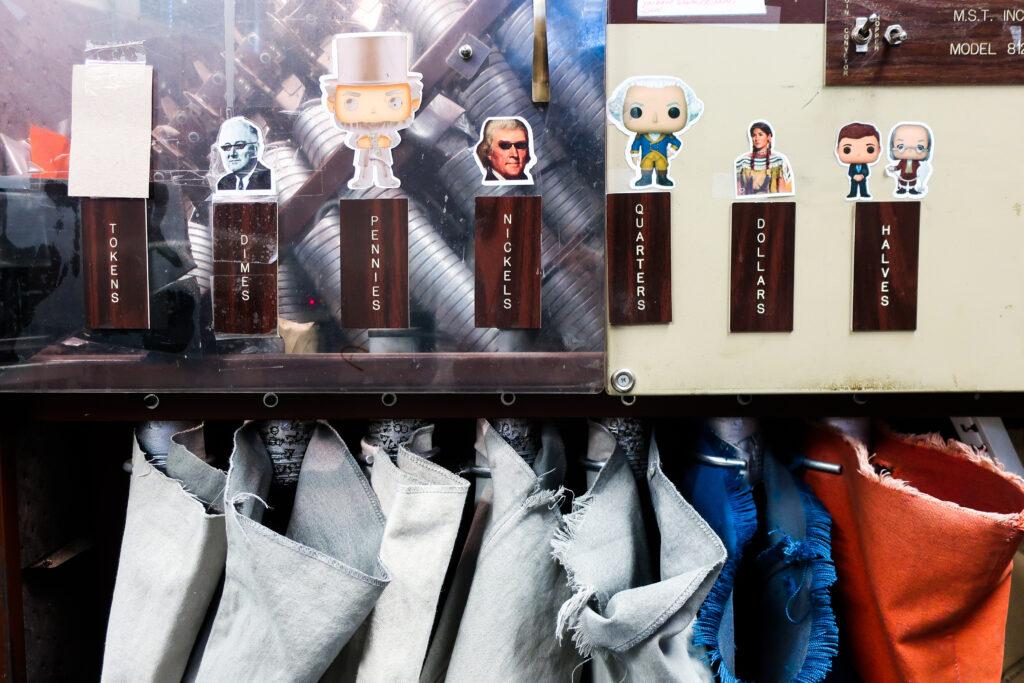

Cash comes into the treasury facility from all over the sprawling Denver metro in orange metal boxes about the size of a home oven. Workers use rakes to pull bills out and into gray plastic tubs, which are then dumped onto cubicle desks.

“This is the most labor-intensive thing that we do here,” Byron said. “My people spend about two-thirds of the day sitting and sorting dollars.”

They weed out paper fare tickets, counterfeit bills — usually finding a handful every day — and tightly stack the real currency in small plastic tubs. The bills are then fed into an automatic sorting machine.

Coins are much easier to handle. They are fed into a counting machine that uses a magnet to pull out foreign currency, metal washers, Chuck E. Cheese tokens, and whatever else passengers drop into fare boxes.

“We've had people call us and say, ‘Can you find my house key for me? I can't get in tonight,’ “ Byron said. “And we’ve actually found it for them.”

During recent down times, like the initial pandemic shutdown and the August free-fare month, Byron kept busy by selling off hundreds of pounds in “junk coin” — mostly Canadian coins.

“I got well over a thousand dollars for that,” Byron said with a grin.

Even some torn dollar bills can be sent to a federal agency in Washington, D.C., in exchange for credit. Byron recently did that, and hopes to get back more than a thousand dollars. “I’m still waiting to hear from them,” he says.

The work is monotonous, Byron admitted. But he said cash-counting is a desirable position in the company — it’s less stressful than driving a bus and workers still get union protections and other benefits.

“We have very little turnover,” he said. “People like working here.”

CPR News couldn’t interview the workers or photograph their faces for security reasons; RTD doesn’t want to publicize who has access to all of this money every day. The workers all wear smocks or coveralls with pockets sewn shut.

More than a dozen cameras record “every possible square foot” of the counting room, though Byron said there hasn’t been a single security incident since he started working there a decade ago.

OK, cool. But is collecting fares worth the cost?

Financially speaking, yes. Don Young, senior manager of RTD’s treasury, said a recent staff analysis found that the agency spends between 10 percent and 15 percent of the fares it collects to process them.

“That’s pretty standard across the industry,” Young said.

That ratio applies to the sum of all fares, an RTD spokeswoman said — including cash and credit card transactions. So the agency would need to find nearly $70 million to break even if it were to drop fares completely.

RTD CEO and General Manager Debra Johnson has not publicly supported dropping fares, though the agency is rounding the corner on a years-long fare study that will likely lower prices. Young believes the agency should continue to charge passengers.

“People want to pay,” Young said. “They're honest about it and they feel that quality service is worth something.”

Byron agreed, adding that fares are also a way for the agency to control who rides public transportation.

“A lot of people get on the bus that wouldn't normally ride, and they set up camp,” Byron said. “I'm not judging. I'm not saying that we shouldn't do something about helping these people … But I'm just saying, this is something that we'd have to deal with.”

RTD’s own recent experience casts doubt on that assertion, though. The agency found “no widespread impacts to operations … as a result of non-destination individuals” and little change in crime reports during free-fare August.

RTD won’t stop accepting cash fares either, Byron said, because it’s the most accessible form of payment for its neediest passengers. And as long as it does, there’ll be a crew in Denver making sure the numbers add up.