The last time Robin Farris walked free in early 1991, most cell phones were the size of sub sandwiches. The world wide web was in its infancy. George Bush — the first one — was the U.S. president. The Soviet Union still existed.

The year before, Farris had killed her former lover during a quarrel and was sentenced to life in prison with no chance for parole for at least 40 years.

But just before Christmas last year, Gov. Jared Polis gave her a shot at parole about eight years early, granting her a commutation because of all the changes she had made while locked up, along with her acceptance of responsibility for killing Beatrice King.

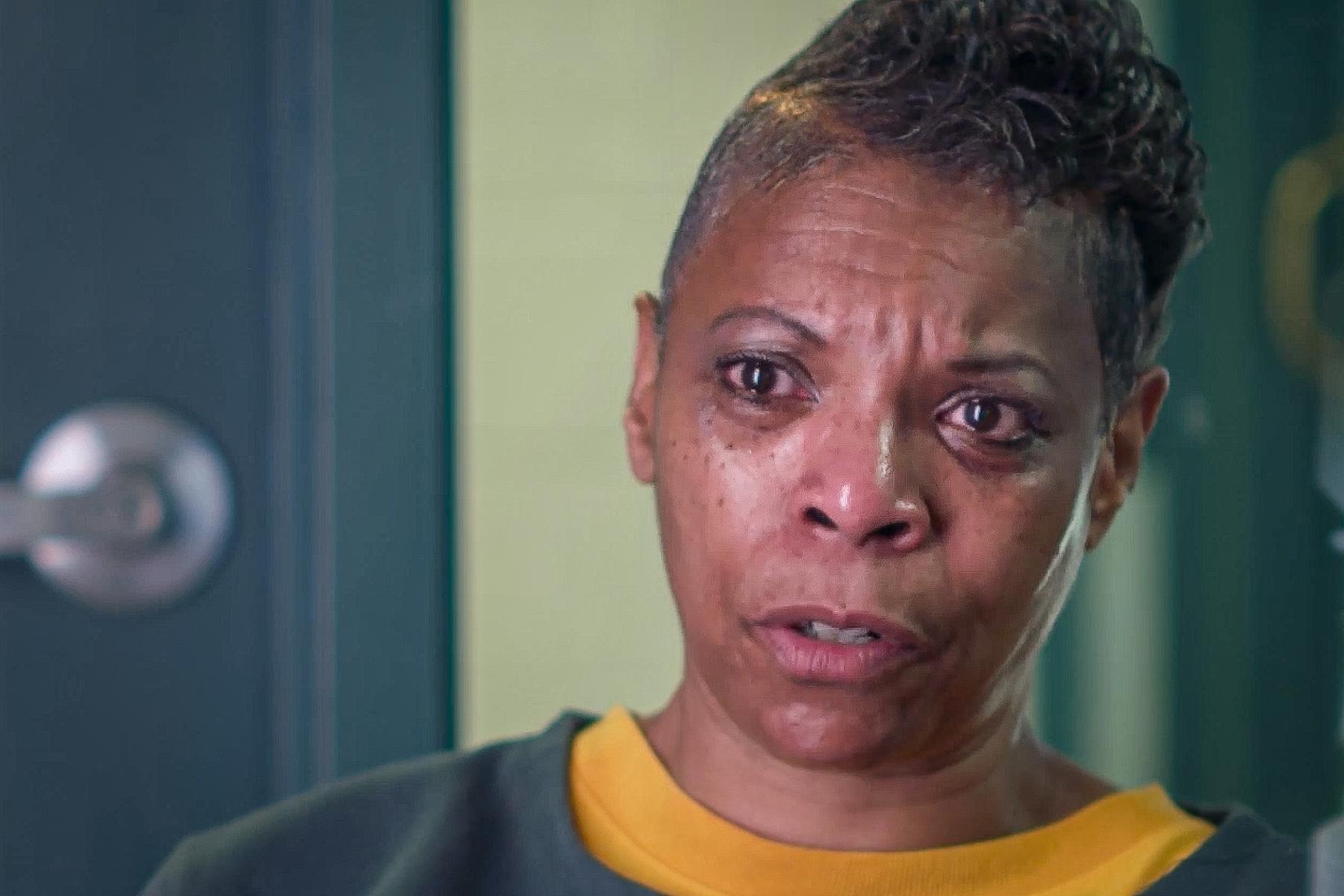

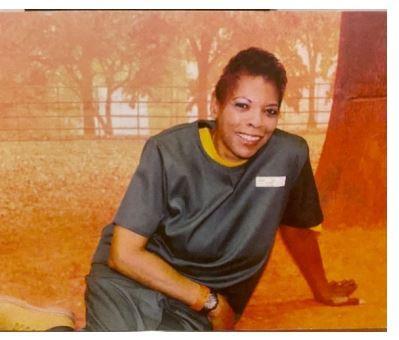

“It was surreal,” said Farris, 61, during an hour-long phone interview from Denver Women’s Correctional Facility, conducted in the presence of her lawyers on Thursday.

She said that late last month, she was told on a Tuesday that she’d have a call with the governor’s office the following Thursday at 9:30 a.m. During a virtual meeting, she heard from Polis’ staffers, who gave her the news.

“There was a lot of crying; there was a lot of joy,” Farris said. “A lot of tears. Tears of joy.”

She immediately called family members based in Pueblo and Aurora, who knew about the 9:30 call, and they were elated.

“It was a feeling of relief, of thankfulness — extreme thankfulness,” Farris said. “Probably some joyful screams that happened as well. It was phenomenal.”

Early release is not a sure thing. She still has to persuade the nine-member parole board she has earned it, and is a good candidate for redemption. She is one of 24 people to whom Gov. Jared Polis granted some form of clemency on Dec. 22.

Farris was the only one on that list to receive what’s called “immediate parole eligibility.”

Of the 23 other recipients of Polis’ clemency grants in 2022, 19 received pardons; one received a commutation and a pardon; and three were granted parole. That makes Farris the only recipient to have to sit before a parole board.

She is unique in other ways also: she is the only Black woman granted a form of clemency from a Colorado governor in more than 30 years. She is also the third-longest-serving woman in the Colorado prison system.

The crime

The murder happened almost 33 years ago. Robin Farris, who grew up in Pueblo, was convicted of first-degree felony murder for the February 19, 1990 shooting of her former lover, Beatrice King, at King’s apartment in Aurora. She was arrested early the following morning.

CPR was unable to locate any of King’s relatives to comment on Farris’s clemency. The governor’s office declined to release documents related to the clemency, so it is unknown whether they were contacted before Polis made his decision.

The memories of that night have never left Farris.

“What happened in 1990 was devastating. It was traumatic for Bea’s family as well as mine. And it definitely should have never happened. I have always since that day taken accountability and responsibility for the death of Bea,” Farris said. “There's a family out there that’s still grieving, and so I’m very mindful of that.”

If released, she said, she will not be allowed to contact King’s family, but if they reached out to her she would welcome it.

“I would definitely want them to know how regretful I am that I took somebody that they loved from them,” Farris said. “How my actions certainly devastated them, changed the dynamic of their family unit. And for that, I am so, so, so sorry. So sorry.”

At the time, Farris was 28 years old and the mother of a six-year-old daughter. After growing up in Pueblo, she moved to New Orleans, where she experienced a violent sexual assault that she didn’t talk about until five years ago.

“Having been the victim of a sexual assault, a violent sexual assault, has had a lasting effect,” she said. “Back in the 1980s when this happened, the narrative around something like this happening didn’t give an opportunity for a woman to discuss it.”

So she didn’t.

“I didn’t tell anybody. Nobody knew anything about it. So I carried this around with me for a long, long, long, long time,” Farris said. Rather than open up, she began to carry a gun so she would feel safe in the world, what she called a “dysfunctional survival skill.” Then she moved back to Colorado, this time setting up in Aurora, where she had family.

She then got into, and was close to the end of, a relationship with King, to whose apartment she arrived carrying the gun. After a quarrel related to their break-up, Farris shot and killed King.

“There were dysfunctions in our relationship, but that in no way justifies my actions or my behaviors that night,” Farris said.

The charge

Farris was not only charged with murder, but also with burglary.

At the time, the burglary charge, when combined with the murder, turned the crime into felony murder, allowing for the long sentence after conviction. Felony murder is when a murder happens during the course of another crime, even if it was not committed after deliberation. Examples of it would include a person driving the get-away car to a robbery where someone ended up shot and killed could be convicted of murder under felony murder rules.

In 2021, the Colorado legislature changed the law. Now, a murder without deliberation committed during another crime will be charged as second-degree murder. That change was among the reasons Polis cited in his letter to grant Farris a chance at parole.

The clemency application

Since her sentence, which Farris began serving in a facility in Cañon City until Denver Women’s was built, Farris has made petitions for post-conviction relief which were all denied, but she didn’t give up hope.

“It started with the direct appeal after trial, and then every single appeal after that. Every appeal was unsuccessful,” Farris recalled. “It was long; it was arduous, and it was unsuccessful.”

That left clemency as the only option to shorten the mandatory 40 years her life sentence required she serve.

In 2014, though a lawyer, she made an application for clemency, but it was denied by Gov. John Hickenlooper in 2019.

In 2020, she made another one on her own, and her new lawyers, Risa Wolf-Smith and Kristen Nelson, wrote a “Supplement to Executive Clemency Reconsideration Packet and Video” to support it in June 2021.

Neither attorney was an expert on clemency. Wolf-Smith, a partner at the firm Holland & Hart, where she has worked 35 years, specialized in bankruptcy and restructuring. The firm allowed her to use some of her time there to work on Farris’ case.

Nelson is currently Executive Director of the Spero Justice Center, a small Colorado-based non-profit that fights excessive sentencing practices in the US. Before that, she worked as an attorney with the Colorado public defender’s office from 2011 until 2018.

In her new role, she decided to write a Law Review article about the work she was doing. She sought voices from inmates. An abstract of the article circulated through correctional spaces and it got into Farris’ hands. She wrote Nelson, sharing her story without asking for legal help.

“I found her writing really persuasive,” Nelson said. It led her to learn Farris had been convicted of felony murder, which Nelson had heard through the legal grapevine might soon be sentenced as second-degree murder. Nelson was also acquainted with Wolf-Smith, and knew she was looking for a more people-focused case to take on pro-bono.

“When trying to match-make and find Risa a client, I thought of Robin,” Nelson said. She went to meet her in prison and, after several hours, she was onboard. “She had a lot going for her in terms of clemency, and had not been successful so far.”

Working a combined 1,000 hours without pay, they argued in the clemency petition that if Farris were sentenced today, she would have been eligible for parole 10 years ago due to the changes in sentencing around felony murder.

The lawyers also argued that Farris had been an exemplary prisoner who used her time behind bars to help and counsel other inmates, to get a college degree, and to learn to be a counselor, which took about 2,000 hours. In the video accompanying the 15-page supplement, several women who were incarcerated with Farris, and have already been released, talked about the value of the emotional support they received from Farris. Several former inmates, as well as Farris’ uncle, based in Pueblo, said they had a place to stay set up for her, and would be able to help her to quickly find work.

Farris already has that settled. Her written parole plan has her moving in upon her potential release with her eldest brother in Aurora. Her cousin has a consulting business in Denver and has offered her a job doing office work to get her started. From there, Farris hopes to strike out on her own, perhaps working in the counseling field she was trained for in prison, helping youth make healthy decisions that would keep them from incarceration.

“Having been incarcerated for decades, coming out of a prison environment, I have to explain to some degree why I have been out of the workforce for so long,” she said. “I’m gonna have to navigate this area and put myself in the best light possible, given the fact that I am a felon, to still be a viable candidate for employment.”

She’s covered when it comes to transportation as well: Her father, who, like her mom, died during her incarceration, kept his car for her, and it’s waiting for her in her brother’s garage.

“He’s treated it like it was pretty much his baby and never drove it,” she said. “He would always say to me, ‘Robin, you are going to need a vehicle when you get out.’”

Her parents also took care of her daughter, bringing her to the prison for weekend visits until she became an adult. Now in her thirties, the daughter, whom Farris called a “strong, strong individual,” is the person with whom Farris is most looking forward to reconnecting.

“Certainly there’s a lot of work to be done between her and I to build our relationship back to a place where it can heal the two of us together,” she said. She anticipates a time when her daughter can speak freely about what it was like to grow up without her. “I want her to have the freedom to tell me whatever, whatever, whatever is in her heart, because she has the right to do that if she’s angry.”

Farris talked about looking forward to being able to get current on the technology she couldn’t experience behind bars. She said she has never surfed the web, looked at social media, or used a smartphone.

“My primary objective is to learn the world the way that it exists today, and to navigate myself through the technological things that I have to learn and know,” Farris said. That includes job applications which were done on paper before her incarceration. “You have to fill applications out online — and of course, never done that.”

The future

Whether early release will come, and what it will look like from there, remains to be seen. In advance of the Jan. 31 parole-eligibility date is a Jan. 25 meeting with one as-yet-unidentified member of the parole board, according to Nelson. That conversation, which will occur virtually, might take about 15 minutes.

Sometime thereafter, the full parole board will meet behind closed doors, hear the member’s comments, and vote on whether to grant Farris parole. If it is granted, it’s unclear how soon she could get out.

“That's the piece that’s a little uncertain regarding the timing,” said Nelson. “We don’t know if there will be any special consideration for her since she was a clemency recipient. We have to wait for her to move up the list and be considered by the full board.”

Upon release, she could be assigned a parole officer, who may impose a curfew. From that point, her lawyers won’t need to serve in a legal capacity anymore, but their connection will go on. Wolf-Smith said Farris’ extended family has embraced them as their own, even inviting them to Farris’ uncle’s 90th birthday celebration in April.

“I want to be part of her life after this,” Wolf-Smith said. “This isn’t going to end for me, after our representation ends.”

And the decades-long ordeal won’t end for Farris either. She said incarceration, as difficult as it was, provided epiphanies and lessons.

“Prison, you know, is my consequence, understandably. But since I’ve been incarcerated, I have experienced so many profound discoveries — not only with who I am, but just witnessing the growth and the potential of so many women around me,” Farris said. “Prison is a place where you can’t hide. You can’t run. You have to face yourself. And I’m grateful, actually having an opportunity to be in a position where I could no longer run from myself.”

She has a lot of help learning to navigate the world upon her release.

“I'll just have to feel my way through and figure that out as I go along,” she said.

Whatever happens, she wants her future actions to counteract her past actions.

“I have authored devastation and been responsible for causing trauma. So I think it’s important that I also be the person that is instrumental in helping others,” she said. “I think it’s important to always create that perfect circle and that cycle and to give back. And so that’s what I want to do when I’m released.”

Editor's Note: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated when Robin Farris first applied for clemency, and the date of Polis's commutation grant.