At Jill and Greg Svenson’s house in Castle Pines, the dogs rule. Indy, Hugo, Mario, plus, “Monty and Molly, the two white ones,” Jill explains.

That pair was an unexpected inheritance.

They joined the pack two years ago after Jill’s mom, Trude, died in December 2020 at 80.

Trude had “at least 10 years left in her, if it weren't for COVID,” said Svenson

In her kitchen, Svenson showed off mementos of Trude Bershof’s life: a high school portrait, family photos, writings and framed newspaper clippings. She said her mom was active and healthy, beloved by friends, kids and grandkids.

“They absolutely just adored her. Just adored her. So she was very spunky,” Svenson said. “And she just had a great heart.”

In November 2020, Bershof tested positive for COVID-19. She was in and out of the hospital, where the ICU was packed and stress shone in the eyes of medical providers.

“They were so overworked and exhausted,” she said.

A few weeks after she first got sick, Trude’s oxygen levels plunged. She was ventilated. An X-ray showed lungs like crepe paper. Jill was overcome with fear.

”I remember sitting in my car, and I was hyperventilating. I just couldn't believe this was happening. I couldn't move,” she said. “I did not want to go up there and say goodbye to her.”

Just weeks before she would have been eligible for a vaccine, Bershof shared a final text with Jill, expressing gratitude. She’d later print out a framed version to hang on her wall.

“Everything that you would wanna hear from your mom before she died. And she sent it in a text not knowing that she wasn't gonna be here the next day,” Svenson said.

Trude Bershof died Dec. 2, 2020, one of 65 Coloradans to die that day, near the peak for the entire pandemic. She’s one of nearly 15,000 Colorado lives lost to COVID-19, more than 1.5 times the capacity of the Red Rocks Amphitheater.

(Officially, as of Jan. 25, the number stood at 14,727 deaths due to COVID-19 on the state’s data dashboard.)

“I think they've been forgotten. And it breaks my heart,” said Svenson. “I feel like we've all moved on.”

Svenson wishes there was some community memorial, someplace, something to mark that gaping void the pandemic left for so many families.

“It's just become a controversy,” she said. “I think it would honor so many people and their families. I would love something like that.”

An early pandemic memorial

Arvada resident Mary Eisenbeis did create something a bit like that in the early months, on a fence in her front yard.

“I thought it would be a way for people to see. And so what I did was I posted the numbers every day,” she said.

Eisenbeis strung up hand-made paper figures updating the national death toll as it climbed into the hundreds of thousands. One neighbor stopped by to tell Mary how she’d first lost her father, then her husband.

“Her mother and she both were now widows, and in this isolation of COVID,” she said.

The neighbor was moved by the words Eisenbeis also hung up: Their Lives Matter.

“She said that was touching to her, that this mattered. It mattered in the bigger picture and, and that other people cared.”

A few months later though, the public debate was getting heated. Then the ferocious winds that fueled the Marshall Fire in 2021 blew Mary’s signs down the street. She decided at least for the time being that it was time to stop.

Not every historic event is memorialized, certainly, but some memorials in the state are fairly permanent, like at the state Capitol.

I wanted to find out who is memorialized in Colorado and whether anyone had given thought to mark the lives lost to COVID. At the state Capitol, I met Nicki Gonzales, a Regis University history professor and former state historian.

West of the building, an old statue is now gone. “It used to be the pedestal that held the Civil War soldier,” she noted. It’s being replaced with a sculpture of an American Indian woman mourning the atrocities of the Sand Creek Massacre.

Nearby we find a plaque with the text to the Gettysburg Address. Down the hill, there's a replica of the Liberty Bell. Directly across from the Capitol, there’s a prominent obelisk next to a stone and concrete monument to Coloradans who died in World War I, World War II and other prominent conflicts in Korea, Vietnam, the Persian Gulf and Afghanistan.

Around Colorado you can find memorials to prominent citizens and sports heroes, victims of 9-11, fires, floods, mine disasters, and mass shootings.

Is there any memorial anywhere in Colorado to the pandemic? “Not that I know of,” Gonzales said. “So, I've asked my historian friends if they knew of any public memorial and, and we couldn't come up with anything.”

This despite the coronavirus pandemic claiming more Colorado lives than the flu pandemic a century ago (for which she also knew of no public memorial), more than any other historic event we know about.

Why?

“Well, I think we're still in the pandemic, and so it's hard to memorialize something that you're still in the midst of,” said Gonzales, who is chairing the governor's commission on renaming geographical features in Colorado. “I think it's been such a politically divisive pandemic period that we haven't really grappled with it enough yet.”

What do we know about these 15,000 lives?

Just who were those 15,000 lives lost to the coronavirus? We don’t really know that much about them.

One group at the eye of the storm was Colorado frontline health providers. But no one seems to have even a reliable count of how many of them died due to the virus.

The first year of the pandemic, more than 3,600 health care workers died in the U.S., including 33 in Colorado, according to an investigative report by the Guardian and Kaiser Health News. The total pandemic number may be in the hundreds, but it’s impossible to know.

The state does track the occupations and industries of those who died, but the categories are broad (healthcare practitioners and technical occupation, healthcare support occupations) and reflect the occupation/industry at the time of death. Also, the health department points out that recording a specific occupation/industry is not intended to imply a connection between that occupation/industry and cause or timing of death.

At one time, the Colorado Nurses Association explored a way to honor those lost, said the group’s Colleen Casper, in an email, but it never came to fruition.

“It was always, and still is, a balance of tackling the ongoing critical shortages of frontline nurses and other staff, with honoring those we lost,” she wrote.

The Colorado Medical Society, the state’s largest doctor’s organization, also said it didn’t know how many physicians died due to COVID-19. A representative said there is one national online memorial for physicians, with just a few names (none from Colorado) and another voluntary site for health care workers, which was last updated in June 2021.

The loss of colleagues still weighs heavily, said Dr. Michelle Barron, an infectious disease physician at UCHealth on the campus of CU Anschutz, which cared for more COVID-19 patients than any other location in the state.

It was easy to ask, “could we have done something different? There's a lot of guilt,” she said. “It's like being at war, you lose people in your squad. It's a big deal. Like when you lose that member of your team, it hurts to the core and it takes a long time to recover, even if everything was done right.”

She said had things played out differently the death toll could have been higher. She said she likes the notion of finding a way to memorialize those who’ve died.

“It's a good idea. It's something that we might need to think about because all of us were impacted. I don't know anyone that doesn't know someone that didn't die from this,” said Barron. She noted she also lost an aunt and uncle, who she grew up next to in Laredo, Texas.

Essential workers, including immigrants, are also thought to perhaps make up a large share of Colorado’s coronavirus victims, but there seems to be no exact figure.

“Just in general, COVID has hit marginalized communities a lot more and so I would assume that because of that we've had a lot of the deaths,” said Bianey Bermudez of the Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition. “A lot of the time for undocumented folks in our community, you just kind of become invisible, and so there's no data on this.”

She said that anecdotally the coalition was aware of many “older folk who were just working through the pandemic and then it was just like one day to another, just passed away because of COVID.”

Many didn’t have health care or a regular doctor to visit.

She said many people were mourned during annual Day of the Dead events.

“Death was so prevalent,” she said, “We had more people to mourn.”

Thoughts on how to memorialize

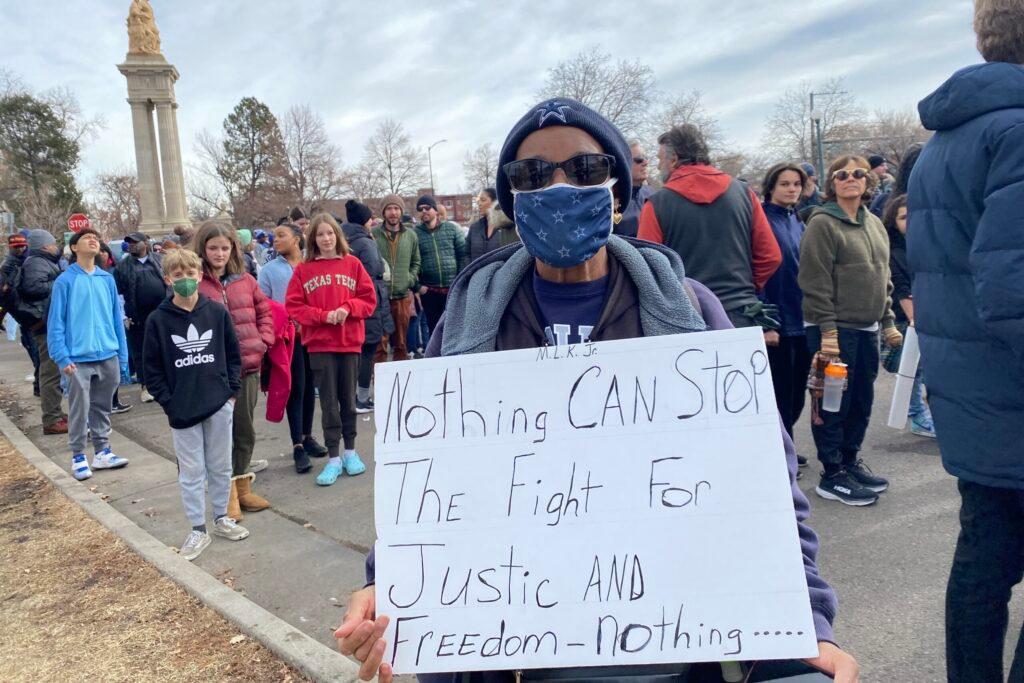

Thousands turned out recently to honor a person who is memorialized in Denver: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose statue fills a prominent space in City Park.

Sixty-nine-year-old Berda Steen was there, wearing a facial mask, one with the stars of the Dallas Cowboys, a bold move in Bronco Country.

She said she’d lost someone to COVID.

“I had an auntie, my daddy’s side, in Victoria, Texas, passed away in a nursing home.”

She emphatically endorsed the idea of properly remembering those who are gone.

“Yeah! We all, every state, need to remember the people that passed away with COVID, you know, they, they didn't know. A lot of people didn't know they had it.”

Up the street, dozens marched with a banner for Servicios De La Raza, a social services organization. One of them was Dr. Ricardo Gonzales, no relation to the historian I talked to earlier. He said the pandemic has hit the Latino community hard. “Death, illness, long COVID. You see a lot of people who are suffering the consequences of the virus that cannot work,” he said.

He’s a bit skeptical about a COVID-19 memorial. Gonzales doubted it would change anything but said perhaps it could serve as a cautionary reminder to try to prevent these things from happening again.

Pandemic amnesia

It seems the farther the pandemic has extended, the less often tribute is paid to people on the frontlines as well as the mounting numbers of those who died.

Long gone are the days of most people saluting health care workers with the evening howl or by putting up signs in yards or businesses.

After the U.S. passed the 500,000 death threshold, President Joe Biden pulled back on marking grim milestones as the numbers climbed higher, now well beyond a million.

Gov. Jared Polis has followed a similar course.

Early in 2021, with the pandemic nearly a year old, Polis made the crisis a centerpiece of his State of the State address. He told Coloradans “many of you are facing some of the toughest times in your lives.”

“Tragically, as we know, not everyone has made it through,” he said. “As of today, Colorado has lost 5,655 people to COVID-19. Each loss seared into the soul of our state.”

The total number of Coloradans who’ve died is now almost three times more than it was when Gov. Polis delivered the 2021 speech.

But in this year’s state of the state, after winning reelection, the governor focused on housing and barely talked about the pandemic, the crisis that dominated his first term. It earned a sole reference: “We’ve gone through a lot these last four years, Colorado. COVID-19. Shootings. Devastating wildfires. Record inflation. Spiraling hate speech.”

A place to remember

On a cold, windy late afternoon, Jill Svenson and her husband, Greg, went to Denver’s Fairmount Cemetery to visit the grave of Jill’s mom.

The couple walked slowly up to the gravesite.

Trude Bershof. Born March 28, 1940. Died Dec. 2, 2020.

On the headstone, there’s a star of David, a rose, and an inscription, describing Trude as an embodiment of light and love.

“It's really hard. This is where we had the funeral. It was sad,” she said.

Due to strict protocols at the time, Jill Svenson said there was hardly anybody there to say goodbye.

She thinks many Colorado families also long for a way to process their trauma.

“I think just having something to represent all of them would be amazing,” Sveson said. “A place, somewhere people could go and say, you know, ‘that was my uncle, my mom, my dad.’”

She wonders if it’s time for Colorado to not just count the lives lost, but fully remember them, too.

Correction: A previous version of this story misspelled Trude Bershof’s name.