John Fielder has an artist’s eye for spotting Colorado’s most beautiful landscapes. And he has the left-brain ability to turn those scenes into well-executed photographs.

He also has a shed filled with skis, rafts, boots, climbing ropes and backpacks—the all-important equipment that has helped him get to every remote corner of the state to capture Colorado’s most gorgeous scenery.

That shed is where Colorado Matters senior host Ryan Warner’s recent visit with Colorado’s best-known photographer began.

Fielder’s outdoor gear shows that it has not been easy to reach every square mile of Colorado to take the more than 200,000 photographs that have become the iconic catalog of the Centennial State’s beauty.

The 72-year-old Fielder is now donating a gift of the best of those photographs to the state he has called home for nearly half a century. He is giving his life’s work to History Colorado and thus to the people of Colorado. It will be free for anyone who wants to see Fielder’s work digitally. It will also be part of rotating displays at History Colorado.

Fielder’s gift includes more than 5,000 photos he selected from his vast trove. It also includes reams of narratives that are part of his 50 books, along with oral narratives explaining what it took to capture some of those photos and Fielder’s thoughts on what drew him to special places. Some of the equipment it took to get there, as well as some of his photography apparatus, will also be part of the display.

At his remote home up a four-wheel-drive road above Silverthorne where Fielder welcomed Warner, the walls are decorated with some of his well-known images. But it is the view of the Gore Range and its Eagles Nest wilderness peaks outside his windows that draw Fielder’s attention.

At times, when the light is just right and the beauty is too much not to capture it for others to see, Fielder will point his camera out this window. He has a hard time ignoring a good photo opportunity.

For the past 15 years, this home has been Fielder’s hermitage where he can escape people and indulge his predilection for being alone. He refers to himself as “half hermit.”

This is where he spent much of the past couple years scrolling through his photos and memorabilia — a chore that enabled him to mentally revisit all the places he has been over decades.

“Loving nature drove the success of my photography,” is how Fielder explains his vast legacy that is as visually iconic to Colorado as the late John Denver’s musical tributes.

It also gave him the chance to be a bit philosophical about what he is able to give to Colorado — a gift he notes would normally come after one’s death.

Fielder didn’t want to wait. He is a healthy and hearty septuagenarian who has plans to keep hitting the trails and rivers with his two titanium knees and one titanium hip, but he found a good fit for a ‘living donor’ agreement with History Colorado.

“I am far from having a foot in the grave, but I didn’t want to put the onus of having to deal with my life’s work on my kids,” Fielder said. “Working with History Colorado, I was able to whittle the best of my photo collection down to 5,000. I also have an emotional connection to History Colorado because I’ve been a history buff for as long as I’ve been a photographer. I have always been fascinated by the history of landscapes I am exploring.”

The passing off of his life’s work also gives him another reflection.

“I’ve always believed that on our deathbeds, you have to ask yourself, ‘Was I a net gain or a loss for the planet?” he said.

For Fielder, part of the net gain has been a longstanding commitment to conservation. Early in his career, he realized that his photographs might be drawing more people to the backcountry so they could see for themselves what they were viewing in his photos. That was a good thing because he wanted others to experience nature’s beauty with all their senses, as he always has. But too many people without proper respect for nature, could create problems.

He committed to make conservation as much a part of his work as making pictures.

He helped push through the passage of the 1992 Great Outdoors Colorado Trust Fund Initiative that invests a part of Colorado Lottery proceeds to help fund conservation and recreation projects. He also was a champion for Congress’s Colorado Wilderness Act of 1993, working with former Sen. Tim Wirth to produce pictures that would help legislators see what was so worth saving in Colorado.

At that time, his goal was to preserve the best of the state’s natural areas. He has a new goal today: to give future generations a baseline image of the natural world as he captured it from 1973 to 2022.

He hopes scientists will use his images to “understand that planet Earth is changing faster and exponentially more than we ever thought it would change because of climate change and global warming.”

“I hope people in a decade will look at what happened from my day to their day — look at it and extrapolate and ask ‘How do we change to protect this place we love?’”

Fielder’s love for Colorado blossomed when he was in middle school. He grew up in various parts of the east coast. He attended a private school where his life was inextricably linked to an unforgettable teacher.

Just talking about Dolly Hickman, makes Fielder a little misty.

“Dolly Hickman was unique on planet Earth,” he told Warner.

She would take a group of kids on five-week tours each summer that looped around North America. Fielder went along on two of those trips, snapping pictures along the way with his Brownie Hawkeye camera.

The little band of travelers, with parental permission slips, packed into a van with Mrs. Hickman and traversed the continent from southern Mexico to northern Canada.

A stop in Rocky Mountain National Park was the highlight for Fielder. It was where he declared to Mrs. Hickman that he was going to live in Colorado someday.

First, he had to graduate from Duke University with an accounting degree. That would lead him to jobs with May D&F and Denver Dry Goods stores in Denver.

When he wasn’t working in the stores, he was exploring the backcountry to revel in the scenery and to bring it back to the city with him in film images.

Fielder says his business background was instrumental in his success as a photographer. He knew how to keep accounts, market, sell, and judicially use loans to get him through lean times. It didn’t take him long before he was a full time professional photographer who also happened to have a head for numbers to go with his eye for beauty.

He has also always been something of a science geek — another talent that has helped with his success as a photographer.

“I’ve had to be something of a physicist to understand the quality of light and color and the intensity of light,” he explained.

He is a topographic-map master, too.

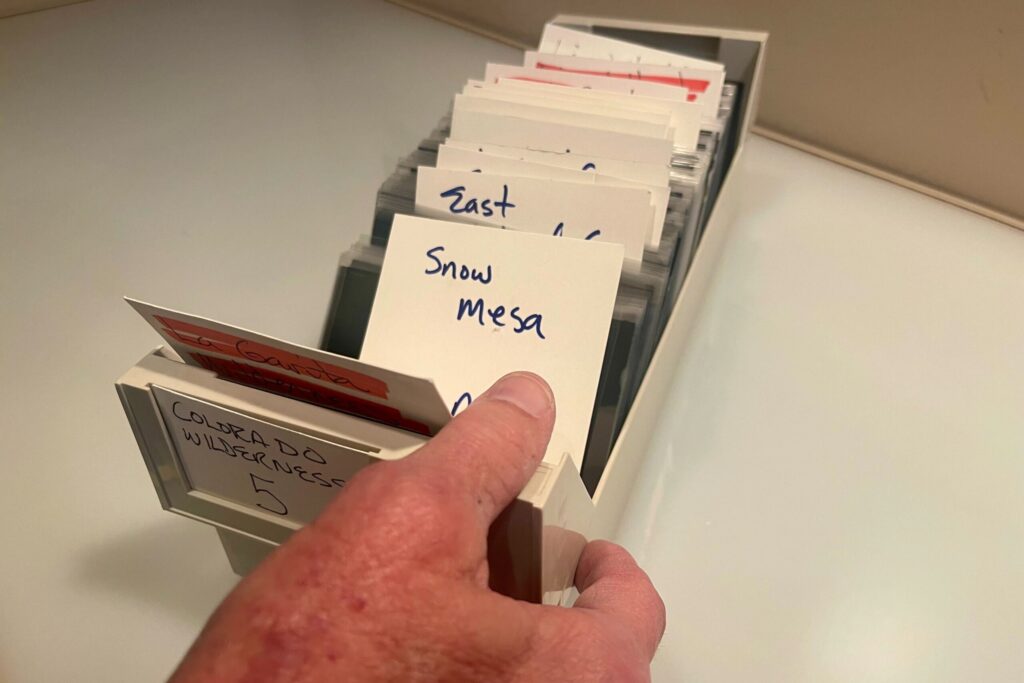

He eschews Google Earth and other digital mapping devices. Fielder uses topo maps obsessively to figure out exactly where he should be at exactly what time of morning or evening to capture the best light on a peak or other feature. He said that helps overcome one of his foibles; he gets antsy waiting around for a photo opportunity to be just right.

Fielder also insists on overall planning for his photographic expeditions.

“You need a backup plan for your backup plan,” he said.

That has helped him out of some tough situations in the backcountry. He guesses he has had to self-rescue about 100 times. In one of his most recent escapades, a bear came into his Gore Range camp and scared his llamas so badly that they pulled up their stakes and took off. One reappeared the next day, but it took nine days to find the other one, half dead and stuck in a ravine. Fielder was able to save it.

Fielder had a more recent close call when he was skiing near Ashcroft above Aspen.

He stopped just below a ridge to turn around and snap a few shots of his friends who were traversing a slope behind him. He felt the vibration under his feet that signals an avalanche and skied as fast as he could to the shelter of trees as the avalanche covered his tracks.

Danger aside, Fielder is never more content than when he is days into the wilderness, often with llamas along to pack the up to 65 pounds of photography gear each trip requires. Since he started using llamas, he has been a little more indulgent with what he takes along. There is now room for a few beers and for plenty of ramen noodles with cream cheese and canned chicken.

That’s his favorite backpacking food. He shared some other favorites with Warner.

Favorite color: tundra green. Colorado wildlife: the bighorn sheep. Flower: columbine, of course. Tree: aspen. Smell: decaying aspen leaves. Nature photographers: Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter.

Fielder said one of his top backcountry loves is the drama of a thunderstorm above tree line, but he also savors the peace found in nature. That has helped him endure some personal tragedies. His wife Gigi died from early-onset Alzheimer’s in 2005. His oldest son TJ died by suicide a year later.

“Those losses are a part of my life. They define me,” he said. “It creates perspective for appreciating life for what you have — and what you don’t have.”

Those losses also propelled Fielder to turn his life’s work into a gift.

“If it weren’t for the losses in my life, I might not be doing what I am doing,” he said.

In his mind, the time was right. The planet needed his gift now. Colorado deserved it.

When the entirety of the gift is in place, Fielder will be back out in his favorite high-alpine tundra shooting more photos. He will be working on another book about some of his adventures in the field. He will also be visiting History Colorado to bask in some memories of a life centered on beauty.