The border between the United States and Mexico used to run through what is now Colorado. After it waged war with Mexico in the 1840s, the U.S. took over large parts of what is now considered the West and Southwest regions of the country.

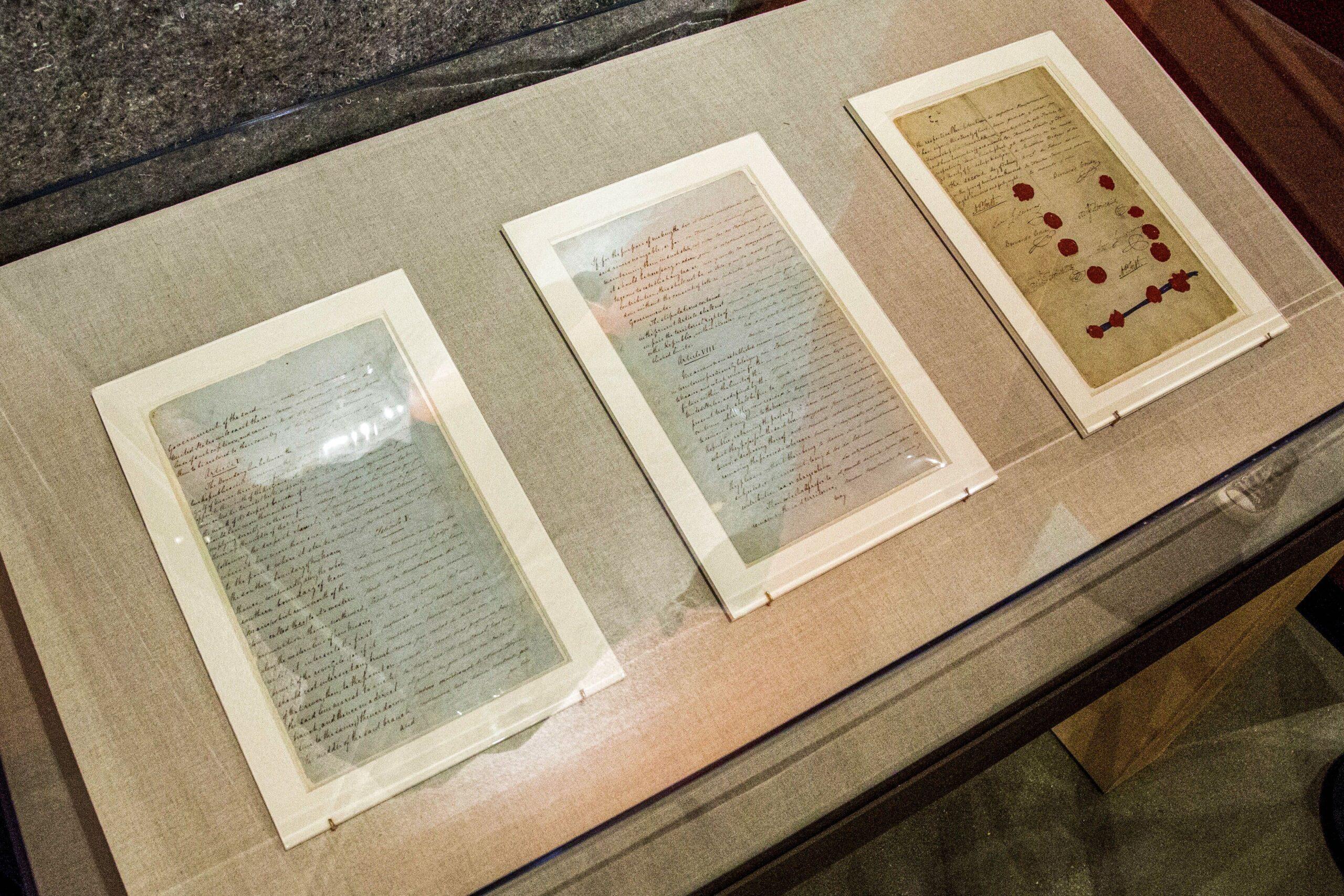

The war ended when the two countries signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, named after the Mexican city where it was signed. Pages from that treaty are on display now at History Colorado Center in Denver, through May 22, 2023. They are being loaned from the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

The treaty marked a huge turning point for America. Colorado wasn’t a state at the time, but as a result of the treaty, the land that is today southern and western Colorado became part of the U.S., along with California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona and part of New Mexico.

Historians Nicki Gonzales and Nick Saenz discussed the treaty and why it matters with Colorado Matters host Chandra Thomas Whitfield. Gonzales is a former state historian and a vice provost at Regis University. Saenz is a professor at Adams State University.

This interview has been edited and shortened for clarity.

Chandra Thomas Whitfield: What should we know about the Mexican-American War, which led to the U.S. getting the entire southwestern U.S.?

Nicki Gonzales: A lot of historians describe it as a war of conquest. Put in the context of American history at the time – the 1830s and 1840s – that was a time of Manifest Destiny, when the United States was an expanding nation. It was expanding westward with the belief that they had some God-given right to conquer those lands, which they defined as “virgin” lands, or lands ready to be “civilized.” So this was a war that was provoked with Mexico over a border dispute. U.S. President James K. Polk certainly knew what he was doing. One of the things that he really wanted was the ports of California, which were incredibly valuable at the time, to open up trade with the Pacific. And so it was a war for the conquest of some very valuable territory.

CTW: Nick, what did the signing of the treaty and the ending of the war mean for people who were suddenly living on U.S. territory?

Nick Saenz: This time period is one in which we actually started to see settlement of the San Luis Valley. So there were attempts in the 1830s and the 1840s to lay claim to land grants in the San Luis Valley. And the war really marked a turning point. The treaty that was hammered out included Article 10, which guaranteed the status of land grants. But ultimately, when the treaty went up for ratification in the U.S. Senate, Article 10 was stripped out, and there was no federal protection for those land grants. So in the San Luis Valley in the years after the war, we saw a process of adjudication that in time led to the dispossession of a lot of those original land grants.

CTW: So could people hold onto their land after the treaty was signed in 1848?

NG: It became increasingly difficult because of the striking of Article 10 from the treaty. Speculators moved into the territory and claimed land rights, according to American land law. As a result we saw a real struggle, and I would say the majority of people lost land because of the land theft that occurred. The treaty really wasn't there to provide any protection of those land rights. It became a separate process, where the U.S. Congress would have to validate or legitimate the land grants through an entirely different process, because the U.S. government did not want to relinquish control over those lands. The separate process meant the U.S. could deny the validity of land grants and thus open it up to American settlement. The result was lots of litigation and lots of struggle.

CTW: What did the treaty mean for Indigenous peoples, specifically, who lived in the areas that became part of the U.S.?

NG: They didn't have representation in the final drafting of the treaty. We’re talking about Comanche, Kyowa, Ute, Apache, and so on. Leading up to the treaty, there were hostilities and conflicts among all groups – the Americans, the Mexicans, and the Indigenous peoples. For them, the treaty meant further dispossession of their lands. All of a sudden they were under the American regime, and so they would lose their lands, and eventually be put onto reservations. It really determined so much of what would come for those Indigenous groups.

CTW: Colorado was not a state when the U.S. took control over these lands. Can you explain what state or states was the land the U.S. got from Mexico part of, and how did it eventually become part of Colorado?

NS: The territory of Colorado appeared on maps for the first time in 1861, and Colorado became a state in 1876. (We're the Centennial State for that reason.) So for the first decade-plus that this part of the country is part of the United States, it's divided into four portions: the Nebraska Territory; the Kansas Territory, which included where Denver is today; Utah Territory, which included the Western Slope; and where I am in the San Luis Valley was part of New Mexico. So even though there was a transfer of the San Luis Valley from Mexican to U.S. hands, the Valley remained a part of the New Mexico Territory, and that influenced a lot of its culture and traditions.

One of the articles of the treaty guaranteed citizenship to people living in the Mexican succession territory, provided that they were part of a state.

CTW: In school, we often learn about the Louisiana Purchase as the big land acquisition that changed the course of the United States. Why do you think the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the Mexican-American War aren't more widely taught as part of US history?

NS: I think some of this depends on where you are in the country. Colorado is getting better at telling some of this story.

But like the Louisiana Purchase, this is a pretty large land transfer: The loss of what was the Mexican North amounted to 55 percent of Mexican territory. I think because in U.S. history, in some ways, we continue this narrative of Manifest Destiny, we see the acquisition of the West as sort of inevitable. We don't pause often enough to reflect on the fact that things weren't so inevitable in real time, and that this was a process that was tremendously fraught for the persons who lived through it.

Editor’s Note: History Colorado financially supports Colorado Public Radio.