About five years ago, Fort Carson army soldier Bradley Benson was sent to the Arkansas Valley Correctional Facility near La Junta in southeastern Colorado. Benson, 20 at the time, was sentenced to 29 years in prison for assault.

“Going from the Army to this, I thought I had found my purpose,” Benson said. “So now I’m in prison and it seemed hopeless, right?”

Benson said his first few years in prison he felt like he could only focus on survival. For the last year, he says his situation has been much different.

More than half a million individuals enter prison each year in the U.S. The vast majority of those people, 95 percent of them, will eventually be released back into society.

In an effort to reduce recidivism and keep young people out of the criminal justice system, Colorado is one of six states experimenting with a new program that focuses on rehabilitation and mentorship. The initiative, dubbed Restoring Promise, recently marked the one-year anniversary of its Restoring Promises Unit at Arkansas Valley.

The program is based around older, experienced inmates — often serving life sentences — acting as mentors to younger ones like Bradley Benson.

Terry Gay is one of those experienced inmates at Arkansas Valley’s Restoring Promises Unit. The 40-year-old has now served 18 years of a life sentence for murder and attempted murder. He, and about a dozen other mentors accepted into the program, completed 10 weeks of training to prepare them to provide guidance and support to those in their care.

“I never thought I’d be part of something like this. This right here is amazing,” Gay said.

The New York-based Vera Institute of Justice — in tandem with the MILPA Collective — developed Restoring Promise after taking cues from similar successful programs in Germany and Norway. Gay and the other mentors work out with the younger inmates, help them through classes and certification programs, and hold group discussions daily.

“I want to add value to these young men so they can be of value to their loved ones,” Gay said. “Someone had to teach me that and I feel like now I'm ready for that.”

The mentors live together with the young inmates in a single cell block, which the group calls “Changemaker Village.” The unit looks completely different from any other at the prison. A big screen TV hangs on one of the bright, multicolored walls. Packed bookcases snake through the main gathering space next to lounge furniture and a kitchen complete with a microwave.

Gay said he hopes his involvement with the program could one day lead to him earning his freedom once again, despite his life sentence. If that does not happen, he said the program is nevertheless providing his life with some meaning and — for the first time in a long time — a sense of safety.

“I can sleep with my door open. I would never do that in prison, I can really do that here. Sometimes I forget to close my door at night,” Gay said.

Ryan Shanahan, director of the Restoring Promise initiative at the Vera Institute, said the program specifically targets the rehabilitation of 18- to 25-year-old inmates because of their typical status as among the most violent and challenging age groups to work with. They are also more likely to end up back in prison once released, so Shanahan said there’s a potentially high return on investment for every individual the program can straighten out.

“Frankly the staff morale on Restoring Promise housing units is significantly higher [as well],” she said. “So, in a place like Colorado that's having staffing shortages, might this be part of the solution?”

Colorado Springs pastor Howie Close, who works with the Restoring Promises Unit at Arkansas Valley, recently spoke to the inmates at a one-year anniversary celebration of the project. He said he was counting on the young men taking advantage of the opportunity being provided.

“The hope is that this program creates better citizens and not better convicts,” Close said.

Close, a former Arkansas Valley inmate himself, said he believes the mentors accepted into the program are genuinely sorry for their crimes. While these men may never breathe free air again, they can work toward the success of this program.

“When you're sitting here and you're contemplating your future, knowing this could be your last stop on earth, every human wants to have an impact. They want to have a legacy,” he said.

The Restoring Promises Unit is just one experimental cell block of about 60 men in the state’s entire prison system. State officials say they are still evaluating its success before deciding whether or not to expand the program. The Colorado Department of Corrections said extra costs to run the program above the costs to run a typical unit at the prison are limited to the extra amenities in the Changemaker Village. They said the Vera Institute covered the cost to retrain staff and inmates.

Despite the program’s nascent status, Shanahan said she believes up to about half of the state’s prison population could succeed in a program similar to Restoring Promise.

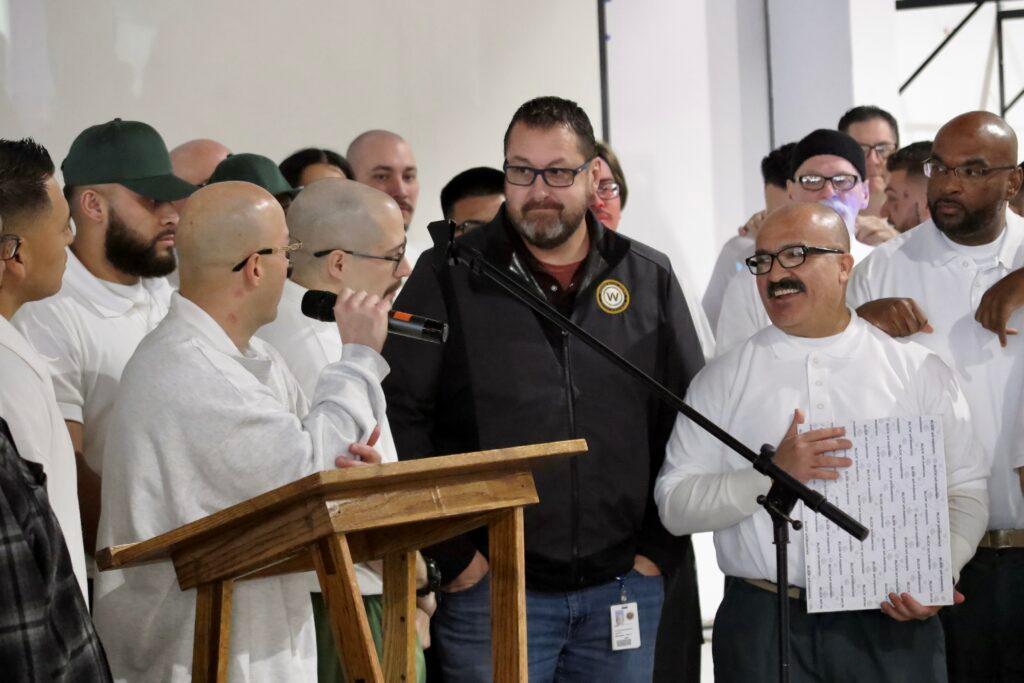

At the one year anniversary celebration, nearly 200 people sat at white folding tables in an open gymnasium across the prison grounds from Changemaker Village. Unshackled inmates, in white polo shirts and green pants, sat with family members watching cultural performances, videos and speeches.

Bradley Benson sat with his parents, Jennifer and Gerry Benson. Bradley Benson is likely facing at least 10 more years before he is eligible for parole. He is currently obtaining a certification as a personal trainer, a career he wants to one day pursue outside the prison walls. Until that time, he’s hoping to eventually move into one of the Restoring Promise mentor roles.

“Having a child in prison is devastating and heartbreaking,” Jennifer Benson said. “I never thought we would go from proud army parents to prison parents.”

But since her son moved into the Restoring Promises Unit a year ago, she said she and her husband have been finding more joy at home.

“This last year has made us more comfortable in our own lives knowing that he's doing better. And if he's doing better than we're doing better because we are serving his entire sentence with him,” she said.

This story has been corrected to include who started the Restoring Promise Initiative.