Whenever high school senior William Schimberg saw his grandfather, he said they would “wrench” on something.

“Whether it be a lawnmower or his truck, we always found something to take apart and put back together,” he said.

Classmate Caden Mallett’s grandfather owned a trucking company and was a firefighter, “So he was big into the diesel truck.” As a child, Mallett amassed little models of diesel trucks, became a NASCAR fan and has always had this goal: to be a diesel mechanic.

Both boys found a place where they can unleash their passions for tinkering on motors, diagnosing mechanical problems, testing brakes and aligning steering systems, and even learning how electric vehicles function, all while applying the science they learn in their regular high school classes.

These Cherry Creek School District students hope to be part of a new generation of auto mechanics who know their way around an electric battery as well as they do the internal combustion engine.

“It means a lot to me that I get to come here every other day for three hours and work with my hands,” said Mallett, looking around the clean, spacious, modern automotive technology facility that is his part-time high school, the Cherry Creek Innovation Campus in Centennial, a stand-alone, state-of-the-art campus in the Cherry Creek district.

“Walking through that door and seeing all this here really changes your perspective,” he said. “Instead of just walking into a classroom and seeing a bunch of desks and saying, ‘I got to sit through a lecture now.’”

The facility is providing the type of education thousands of Colorado students want and employers are asking for.

Cherry Creek students can enroll in one of seven pathways: business services, IT and STEAM, hospitality and tourism, infrastructure engineering, health and wellness, and aviation or automotive. They learn real-world technical skills part-time while continuing to take classes at their home high school. It also offers more than 30 nationally recognized industry certifications. The facility was paid for by a voter-approved bond.

Today students hover over a bright red car frame. Not just any car.

They’re strategizing on how to remove a lithium-ion battery out of an electric vehicle. They’re disassembling the whole car, in fact. Teacher Brian Manley, who oversees the automotive pathway, said this special program will make these students ready for good-paying jobs right when they graduate.

“They’re learning not just the wiring but also how the inverter works from high voltage to low voltage, the traction motor that they’re going to take out in a little bit… and then all the basic chassis structure, things they’ve already done, suspensions, steering, brakes and alignment,” he said.

Before they move to assembling and disassembling the car, another group of students is wiring relays, an electronically operated switch, on a circuit board.

“We’re looking at the more in-depth electrical systems and just basically being able to see what electricity makes up for compared to a combustion car,” Rufino Trujillo said.

The electric vehicle is a new experience for the students. There are few moving parts — around 20 in the average electric vehicle versus 2,000 in a gas-powered car. Electric vehicles need far less maintenance and repair than conventional combustion engines. Brake systems last longer. There are no mufflers, radiators or exhaust systems. Their batteries are projected to last between 100,000 and 200,000 miles.

California projects nearly 32,000 auto mechanics jobs will be lost with the ban on new gasoline-powered cars by 2035. But student Mallett said electric vehicles will still need repairs.

“You still have your brakes, your tires, your tire rod ends, all that mechanical stuff that has to do with the steering, that’s still involved within the car,” he said.

There’s different tools and training required, including reprogramming computers on the car. Right now, there are only about 73,000 registered electric vehicles in Colorado. Gov. Jared Polis has a goal of 940,000 EVs on the road by 2030.

“With us having this experience in this class, we’re already getting a jump start on other technicians that haven’t worked on electric vehicles and they don’t know the schematics,” Mallett said.

In addition, it will take a long time before internal combustion engines are off the road.

“These guys have to keep our fleet going for the next 20, 30, 40 years,” Manley said.

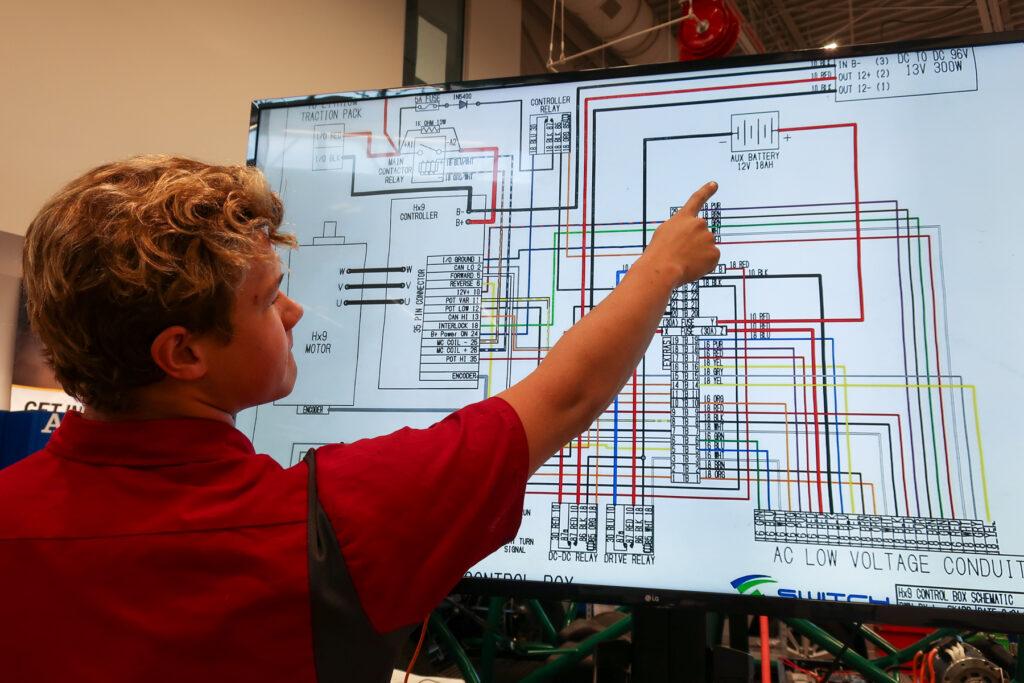

In this class, students first master gas-powered cars then they move to hybrids and finally all-electric vehicles. They first learn off a schematic, a complex spaghetti-like drawing of color-coded wires that student William Schimberg seems to know like the back of his hand.

He explains the red, black, yellow and green wires — which are for grounding, which are for power.

“It all slowly starts to piece itself together when you work around it enough.”

Schimberg said this innovation center, which allows students to shadow industry partners, opened up possibilities for him. He’s said he sees 12th graders go to college and still have no idea what they want to do.

“I feel like people can come in here and before they go to college or they decide on trade school, they can decide if they want to do this for the rest of their life. This is a huge eye-opener rather than just learning about an experience through the classroom,” he said.

Schimberg also likes the opportunity to work at his own pace, unlike in a regular classroom. Students can switch pathways if they decide one is not the right fit. Some students will go straight into a well-paying job after graduating. Others will go to college. Schimberg wants to study mechanical engineering after he graduates and work in the automotive sector.

“I can use my knowledge of taking cars apart to know how to better design them,” he said.

Thousands of Colorado students prefer learning through doing.

But not every high school or district has the resources to give kids the skills so many want and are in such high demand by employers.

For Beau Martin regular high school classes were always hard, especially history and English. He struggled to retain what he read.

“I was always, like, in the class, the quiet someone who just didn't know what he was doing in class and came here, I found my friends and got to work.”

Not all students learn the same way. And Martin, as he puts on brake calipers, explained that learning hands-on through failure is what makes it stick.

“Mr. Manley’s a great teacher. He’ll let us fail and then try again. It’s through trial and error. That's how I prefer to learn. I feel like it's like once you get it after failing so many times it'll stick with you longer.”

Manley recalls after a project where students building cardboard hydraulic lifts out of syringes, a student turned to him and said, “’It makes sense to me the science that I learned about hydraulics and the principles of fluid transfer, Pasqual’s law.’”

“So those little ‘aha moments’, those little light bulb moments, they happen a lot around here,” Manley said. “Especially with science and physics. They get to see it, touch it, feel it, hear it, smell it. We smell that now with the chemistry of combustion with the engines we've been starting up. You can smell if it's running rich, you can feel what it does when you tune it a different way.”

Manley stands back and lets the kids work, struggle, learn, figure out problems on their own before he steps in.

“I don't think parents (and) the business community, they don't get to see the side of teenagers, they don't get to see how amazing teenagers are as students that can do that and have the skills to work together in a group effectively.”

And when students do argue — there’s a disagreement going on right now over wrenching the right part of the car — resolving that conflict is an invaluable skill, one that employers want.

“That's gold,” Manley said. “Any manufacturer, shop owner's going to pay that student to fix the cars, to be a service manager, to perform customer service skills, to sell their business, to grow their business.”