For decades William Richardson touched the lives of hundreds of young people in his close-knit Colorado community, but many of them had no idea that before then their longtime coach and mentor had already made his mark on Black history, American history and sports history.

For a time even his own children were unaware of all that he’d accomplished and the sacrifices he’d made in his young adult years to play the game he loved — baseball.

In honor of Black History Month, this never-before-told story chronicles Richardon’s journey from a pitcher in the Negro Baseball Leagues, sports leagues born out of America’s racial segregation era, to a Colorado community leader.

'You played for one reason — you loved baseball'

“He played all or parts of four seasons in the Negro Leagues and he kind of epitomized what Negro League baseball was all about,” said Dr. Layton Revel, founder of the Negro Southern League Museum in Birmingham, Alabama. “In the Negro Leagues, you didn't make a lot of money. You didn't play for endorsement contracts with a shoe company or to be a national celebrity or anything else. You played for one reason — you loved baseball.”

Dr. Revel says the Negro League helped form the foundation for Major League Baseball (MLB) today. Richardson would eventually bring what he’d learned in the sport to his work with children in Northeast Denver.

“He was a phenomenal role model for the kids that he coached and taught,” said Dr. Revel. “And he was what an athlete should be, whether they're playing in the major leagues today for the New York Yankees or they were playing for the Lynch Jewelers in Denver, Colorado.”

The Negro Leagues ran primarily between 1920 and the late 1940s, but many teams continued well into the 1950s, well before and even after Black baseball phenom Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in the sport in April of 1947.

“Major League Baseball had an unofficial gentleman's agreement, which says that no Black players will be allowed in white Major League Baseball during the term of Commissioner Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis,” said Larry Lester, co-founder of the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. “He was the commissioner of baseball and he banned Black people from playing in the white majors. He tried to ban all-Black teams from playing all-white teams.”

Lester, who has written, co-authored and edited nine books about the NBL, says establishing the League marked a major milestone for African Americans.

“Negro League Baseball was founded in 1920 and it gave opportunity to Black athletes who did not have the opportunity to play in the white major leagues; and so it filled that void,” Lester said. “Let's note Black ball players started playing ball all the way back to the Civil War, and now with the 1920s, we have the Harlem Renaissance, it's a new age, new dynamics among Black people, we're coming out of World War I and Black people are saying if they won't accept us in mainstream, let's start our own businesses, create our own institutions, haircare products, life insurance, restaurants, other businesses and one business was baseball. Let's start a baseball league — the Negro National League — which was founded by Rube Foster in 1920. They created opportunity where opportunity did not exist in the white mainstream.”

Richardson’s path to the NBL was a remarkable one

Born in 1934 in the small Alabama town of Vinesville, near Birmingham, he fell in love with sports as a kid. He especially enjoyed playing baseball and football. In his teenage years, he made a name for himself playing in the local amateur baseball leagues. Dr. Revel says Richardson wasn’t the only baseball standout in his community. He became close friends with a neighbor and fellow decorated athlete named Willie Mays.

“Willie Mays is a good example of the five greatest ball players of all time,” said Dr. Revel, who is also the founder and executive director for the Center for Negro League Baseball Research. “Everybody thinks about him with the San Francisco Giants, the New York Giants. He made the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Well, the reality was he started playing baseball in Fairfield, Alabama with the Fairfield Stars.”

In a videotaped interview with two of his sons and granddaughter at his Denver home in 2009, Richardson recalled the special relationship he shared with Mays, against whom he often competed while in high school.

“Willie grew up about two blocks from where I lived,” Richardson said in the recorded interview. “Early on, I was really impressed with him as an athlete and we became real good friends. In fact, we palled around together and I've always admired his athletic ability. I thought then, even as youngsters growing up, that he was the greatest athlete that I'd ever seen.”

Richardson himself had earned a solid reputation for being an exceptional baseball player, but as a young adult the chance to play another sport would eventually provide him with an opportunity to venture away from his hometown and receive a free education.

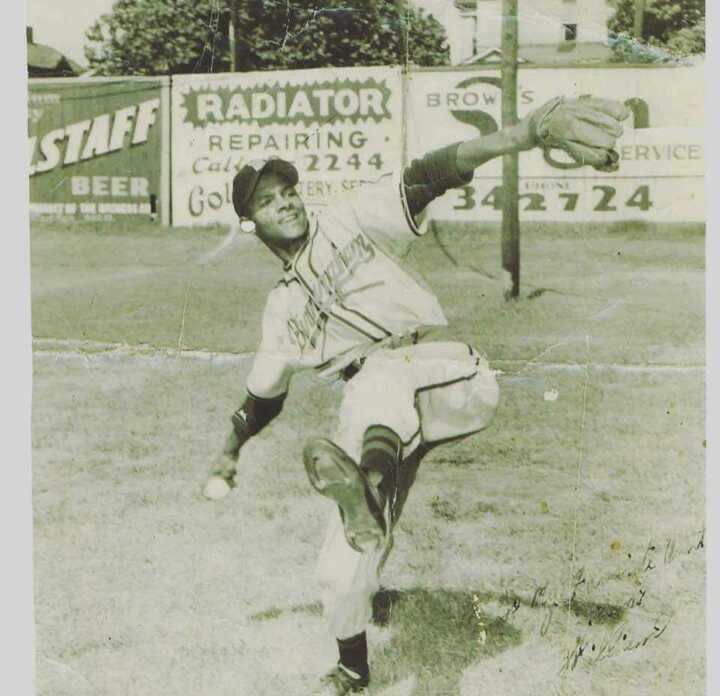

He accepted a football scholarship and played quarterback at historically Black Clark College, now known as Clark Atlanta University. He didn’t give up his baseball dreams altogether though. He tried out for and later signed a contract with the Negro Baseball League team, the Birmingham Black Barons.

“During the summers when he was out of school in '54 and '55, he played with the Birmingham Black Barons,” Dr. Revel said.

'The climate was contentious, somewhat overwhelming ... they had to be creative'

In the interview with his family, Richardson, whose baseball nickname was “Bay Bay,” remembered well the racial tension that was perpetually in play even at Negro League games.

“Race relations were very interesting during that particular time because of the fact that in each city, there was a Black team and a white team,” he said. “The thing that was very noticeable to me, even at a very young age, even before my career began, is that I noticed that at the white games, all the Black people sat way out in the bleachers and during our games that we had whites sat on the first base line and the third base line all the time.”

Baseball historian Lester says the Black NBL players faced rampant racism on and off the baseball field.

“The climate was contentious, somewhat overwhelming, when they're not accepted on the road to stay in hotels or eat in some restaurants; they had to be creative,” Lester said. “So, they would carry lunches on the bus with them, some players would carry a fishing pole in case they came by a stream, they would catch some fish, skin it, fry it, eat it. Then, of course, they had the Green Book, which would tell them what hotels they could stay at and they would use whatever means necessary to get from town to town to play either a minor league team or a major league team.”

However, Richardson and his fellow Negro League colleagues remained steadfast and determined to play the game that they loved. Their passion was largely fueled by the many memorable moments they shared on the baseball field. In his interview with his family, Richardson recalled his most memorable game: July 4, 1953, in Memphis, Tennessee.

“I came in and relieved in about the seventh or eighth inning and got the victory and it was extremely hot day that day, like 102,” Richardson recalled. “We was just chilling out, waiting for the second game to start in the double header and Horace Walker came up to me and said, ‘You’re starting that next game.’ Man, I was completely drained. The Memphis Red Sox, that was a team that was our opposition that particular day. The manager told them not to swing at any pitches, just let him wear himself out pitching. By the third inning, man, I was done. It's like I had lost about 15 or 20 pounds.”

Richardson's pitching ability eventually caught the attention of another NBL team; one much further from home in Detroit, Michigan.

“In 1957, he played with the Detroit Stars,” said Dr. Revel. “So, he played all or parts of four seasons in the Negro leagues with the Black Barons, the Detroit Stars.”

'He was a provider of hope'

Richardson and his buddy Mays had remained close for most of their youth, but his decision to date Mays’ cousin, Loretta Thomas, eventually drove a lifelong wedge between them as young adults. The couple married in January 1957 and immediately started their family.

Richardson graduated with his bachelor’s degree the same year, but remained in Atlanta while his wife completed her studies at the same college. At that time, he also launched his career off the baseball field taking a job working with young people at the Butler Street YMCA, a recreational center in Atlanta that served the Black community.

His work there eventually resulted in a big offer that led Richardson to relocate his young family to Colorado in 1962. Richardson accepted a job leading physical education at the Glenarm YMCA in Denver, one of the few recreational centers in Colorado at the time that was available to Black patrons.

One of his longtime mentees, Terry Patton, says he first met Richardson as a young child at the East Denver YMCA after Richardson had been promoted to the role of executive director, a position he would hold for nearly three decades. Patton, who referred to Richardson simply as “dad,” remembers him as an excellent role model who inspired many.

“He made so many things possible; he made it so that we did not have to be in those streets,” said Patton, now a personal trainer in Arizona. “He kept us employed to keep us out of trouble. He made us understand that anything was possible in this life, but it had to be earned. It was not gonna be given. It's like, man, if he made it, I can make it too. He was a provider of hope.”

Richardson continued working with young people at the East Denver YMCA and even with an ever-expanding family, still found time to play baseball recreationally. Then came what arguably sounded like the offer of a lifetime. Dr. Revel says in his in-person interview with Richardson in the early 2000s, Richardson told him while in Denver he was offered the opportunity to play for the Pittsburgh Pirates, a white team in Major League Baseball.

“I can remember talking to him about it, and it really was very meaningful to me because a chance to get a contract is every young baseball player's dream, because you've got to get signed in order to play in the minor leagues, hoping to make it to the major leagues,” said Dr. Revel. “And what William was concerned with is he had what he considered his dream job working with the YMCA.”

Dr. Revel says he was surprised to learn that Richardson turned down the offer.

“I asked him. I said, ‘Well, was that hard to give up?’ And he said, well, God had blessed him with a lot of skills, athletically, good enough football player to [receive] a college scholarship and get a good education,” he said. “He was a good enough baseball player to play professionally in the Negro Leagues and he recognized the importance that sports had played in his life, and he felt it was his responsibility to give back. The best way for him to do that was working with young people and no better place than the YMCA.”

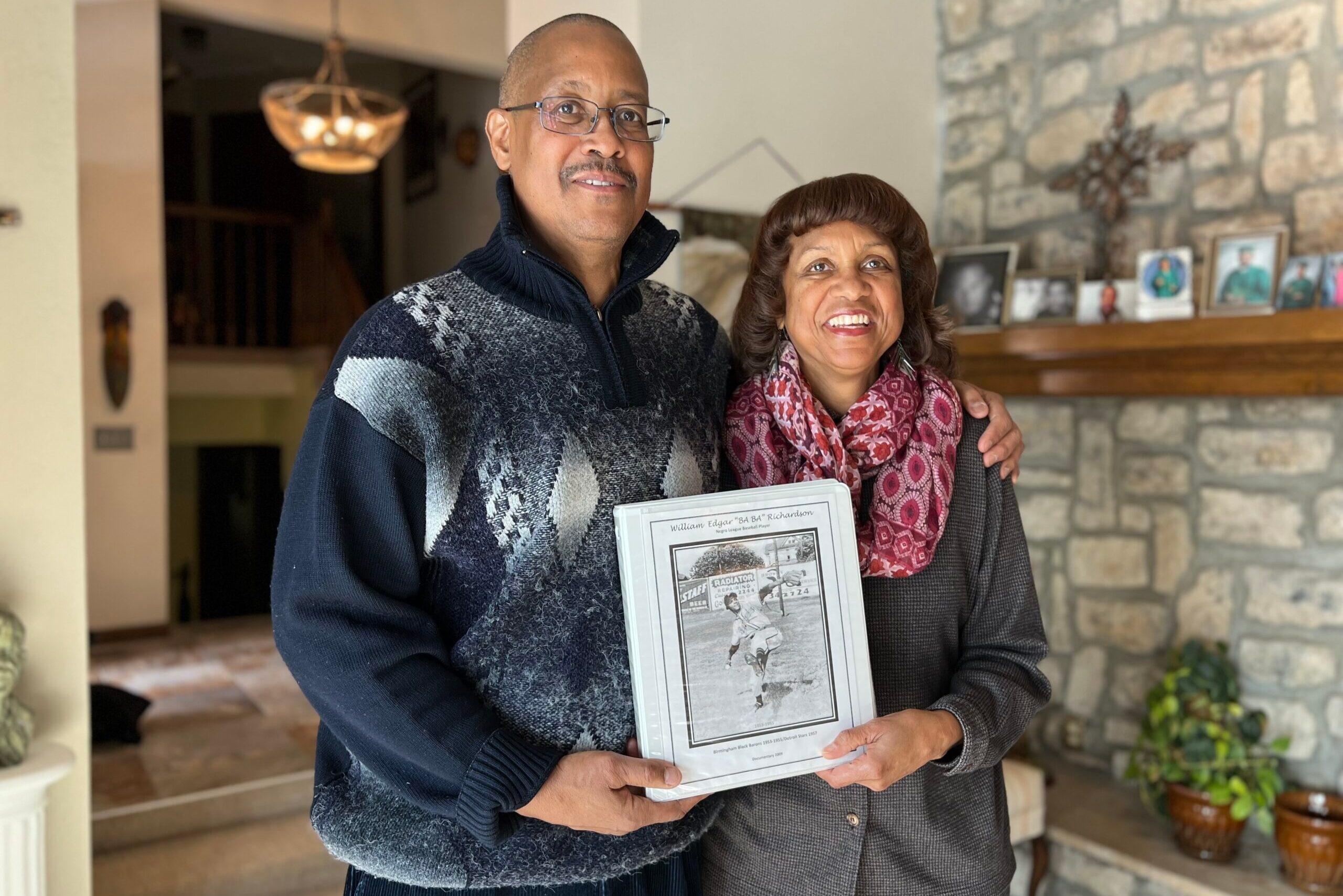

Richardson remained at the East Denver YMCA for more than two decades. Two of the six children he shared with his wife Loretta, Dr. Terri Richardson and Marcus Richardson, both of metro Denver, say that under his leadership the Black kids growing up at the East Denver YMCA learned to swim in an Olympic-sized pool and trained and played in a brand new gymnasium, all of which Richardson had lobbied and fought for.

For many years Richardson also coached the Little League football team. After training with the Toastmasters organization early in his career, he also earned a reputation as a dynamic public speaker who led many fundraising efforts. Later in life he was named “Man of the Year” for his community work.

Mentee Patton says his impact on the children growing up in Northeast Denver in the 1970s through the mid-1980s was so much bigger than coaching them in sports.

“A lot of us came from single-parent homes [and] here's a man and his wife and his children and they're all good people,” said Patton. “We should all endeavor to have that. That's, that's the way you do it, the way that Mr. Richardson is doing it. He instilled that in us.”

'He ended up just where he wanted to be'

Richardson and Loretta divorced in 1991. He later remarried in 1999. Richardson officially retired in 1993 after 34 years with the YMCA organization. The East Denver YMCA officially closed in 2004. In retirement, Richardson took on a third act, working 15 years for the JC Penney store inside the Town Center Mall in Aurora.

His son Marcus Richardson says about four years ago, his dad finally began receiving some compensation for his years playing in the NBL, an effort led in part by scholar Lester who advocated for the MLB to give all living NBL players who’d played at least four years in the league retroactive pensions. He also brokered a deal for many of the players to receive a portion of the money the MLB earned from a popular NBL apparel line.

Richardson died at a care facility in metro Denver on July 13, 2022, at the age of 87. A small private funeral was held a few weeks later.

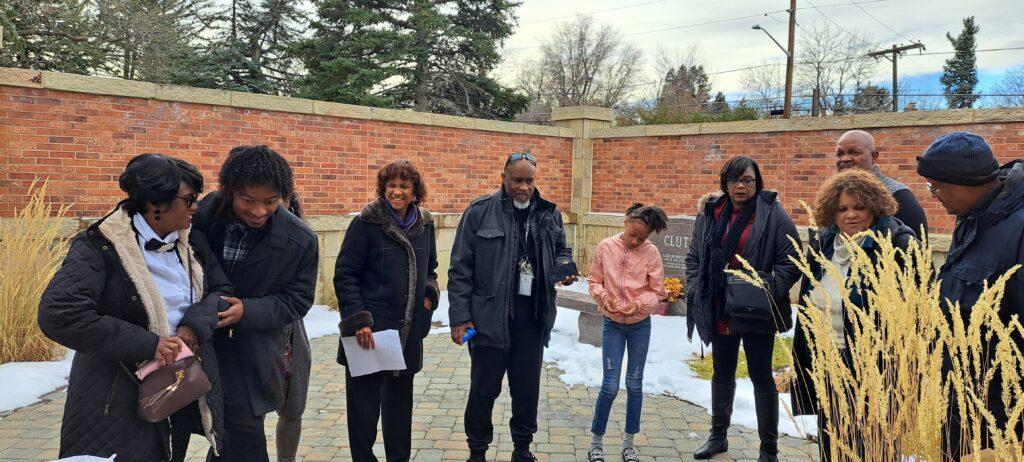

In November 2022, just before Thanksgiving, his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren gathered for another private memorial at Fairmount Cemetery in Denver. They shared personal memories of Richardson and unveiled a memorial bench featuring his name alongside his birth and death dates.

“We can go visit it anytime; it's in a great location; to me it just really honored him even more than a headstone,” said daughter Dr. Terri Richardson. “Something about a bench; you think [of] a baseball player and a bench.”

Dr. Revel says looking back at Richardson’s remarkable life and career, reinforces the widespread sentiment that Richardson made the right choice for his life and career by choosing to remain in Colorado working with youth.

“He ended up just where he wanted to be,” said Dr. Revel, who features a baseball signed by Richardson at his museum in Birmingham, Alabama. “You could look at the look on his face when he was telling you the story about being able to give back to kids — being able to work with the youth of today — and not just teaching them sports, but teaching them how to present themselves to be the best possible person that they could be.”