Do you know the number of the state House district you live in? What about state Senate? Or Congressional?

I do, but then again, I’m a professional political nerd. That said, around election time, I can’t be the only one who has ever gazed at their ballot and wondered: “Why am I in this number district in particular? Who decided that?”

In fact, I know I’m not alone because a CPR fan after my own heart wrote in to ask: How do House districts get numbered? (Was it originally by population centers? Do all state capitals become district 1?) Was there any method of reasoning to the numbering?

The short answer is … there really isn’t an answer.

“Congress does have the power to regulate how congressional districts are structured. They don't have any law on how numbering works, and most states don't have laws on how numbering works either,” said Ben Williams, a redistricting policy expert at the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Some states do follow geographic conventions, either through law or tradition, like starting the numbers in one corner of the state and moving out from there. In California and Florida, the numbers increase as you go from north to south. New York takes the opposite approach — starting its numbering on Long Island and increasing as the districts move upstate.

(Despite the lack of a satisfying answer, Williams said he was glad anyone cares enough about this process to think to ask the question. Hear hear!)

As to whether state capitals automatically get to anchor the first district in each state, well, as logical as that would be, Colorado is actually the exception, not the rule.

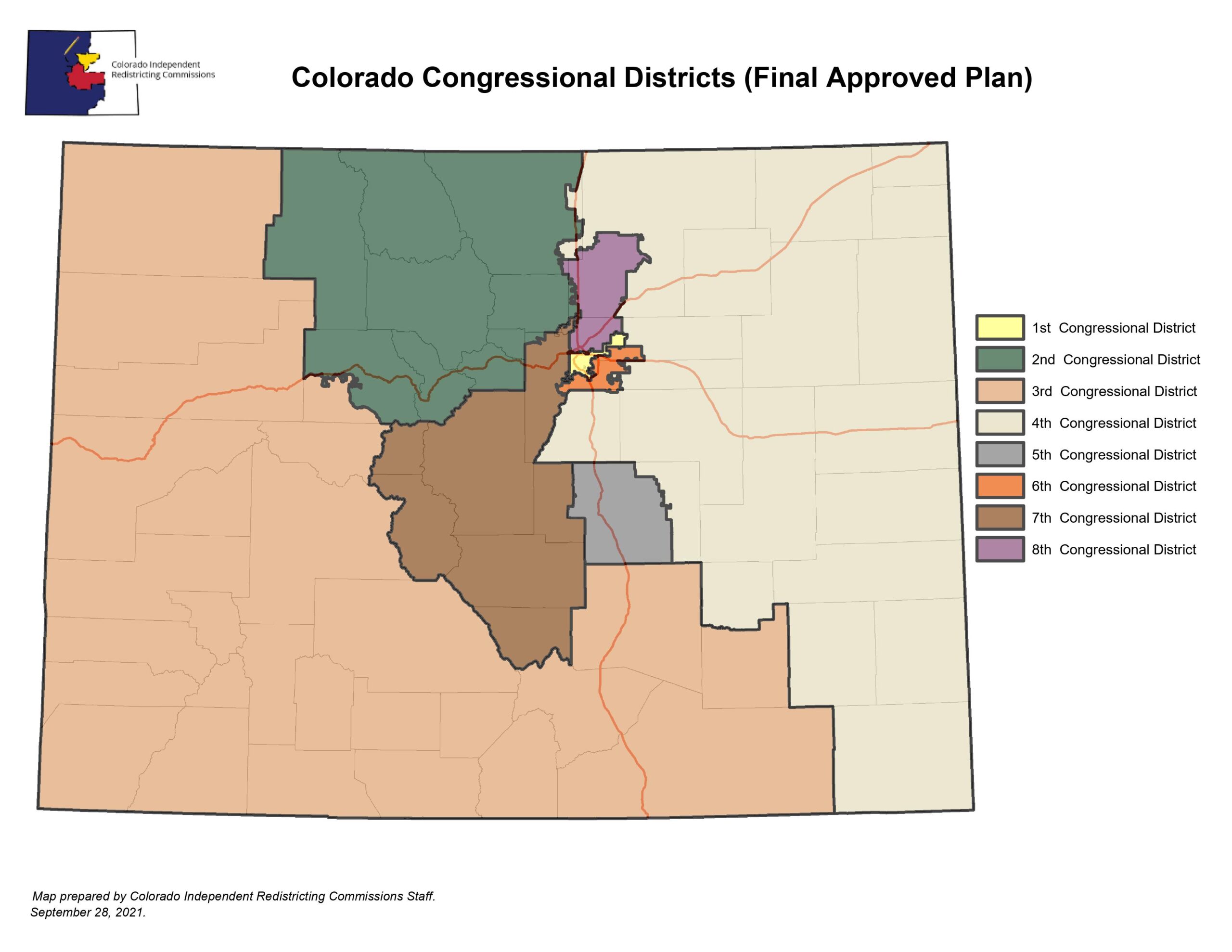

Yes, our first congressional district covers Denver. But just look to our neighbors: The First Congressional District in New Mexico spreads out from Albuquerque. Those in Kansas and Utah both curl around outside their capital cities. And Wyoming is just a single, statewide district.

Many states do appear to try to number their congressional districts somewhat sequentially though: Wherever you find the first district, expect to find the second next door, and then the third, etc.

But again, this is a place where Colorado breaks with a pack. The state has gained four congressional seats over the past six rounds of redistricting and has generally chosen to plop each new district (and its number) in its fastest-growing region, wherever that may be.

So when the 5th congressional district was created in 1971, it was anchored in Colorado Springs. Then when the 6th district came along a decade later, it went to Aurora and other southeastern metro suburbs.

At the statehouse, district numbers are a relatively new thing.

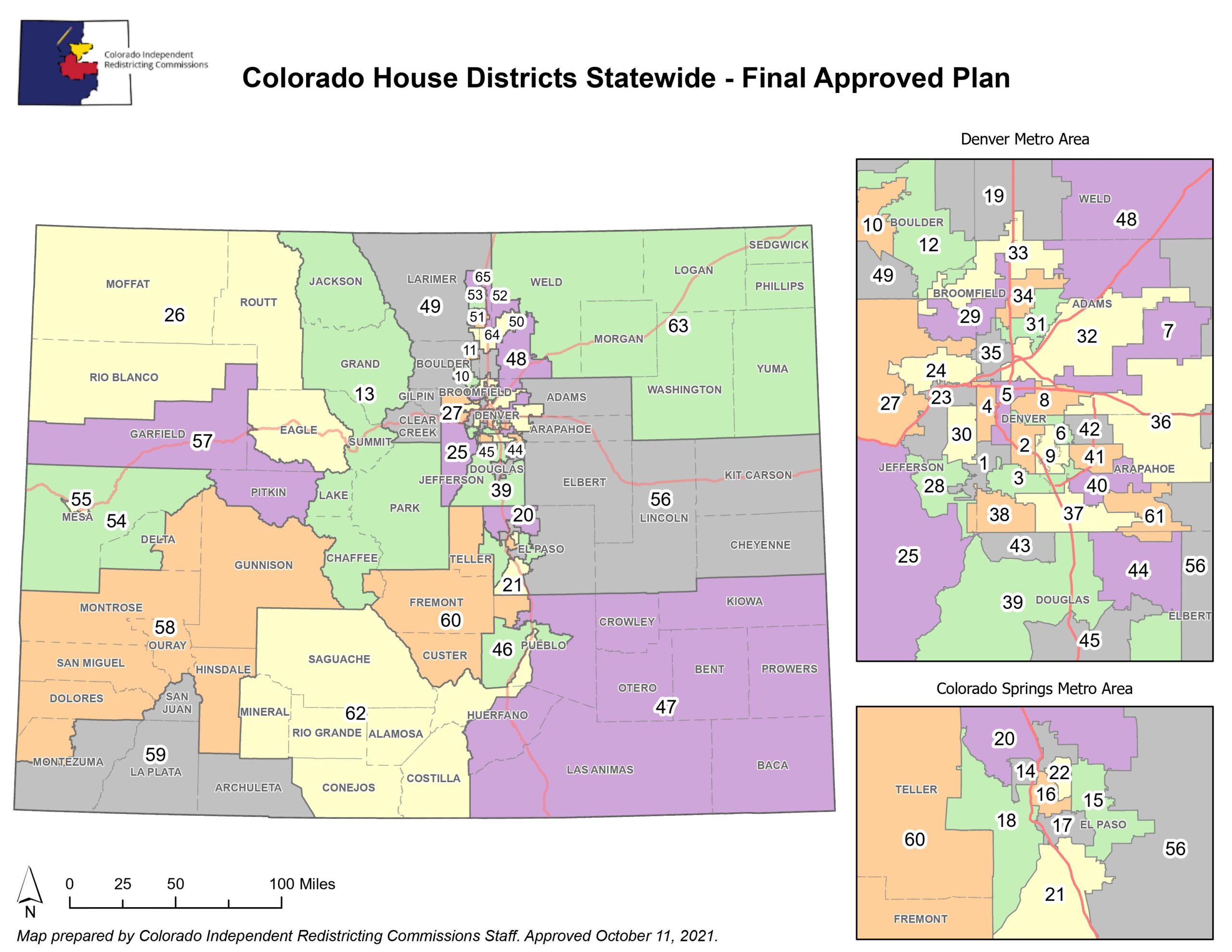

Colorado just went through its once-a-decade redistricting process in 2021, with two independent commissions tasked with redrawing the congressional and state legislative maps. When it came to numbering, they followed a don’t-rock-the-boat policy, agreeing to try to keep things as much the same as possible.

“We used an Excel sheet,” explained Julia Jackson, who served as a staff analyst for the independent redistricting commissions. “Our chair of the legislative commission was, like, a programmer math guy. So he came up with a formula that said, ‘If this much of the land area continues to another district, it keeps the same number.’”

For the most part, overlaying the new map on the old one works to keep things pretty similar, but not always. When they ran out of nearby numbers for House districts around the border between Boulder and Weld counties, the commission had to grab number 19 from El Paso County. And because the law doesn’t let the commissions think about the politicians who currently hold each seat, it also had weird effects for some individuals — like swapping the district numbers for two sitting state senators, Rhonda Fields and Janet Buckner, in Aurora.

But the keep-it-the-same system doesn’t explain why Colorado’s state legislative maps are such a mess, numerically. There are some general patterns — lower-numbered Senate districts tend to be on the outer edges of the state, while single-digit House districts are all in and around Denver. But there seem to be almost as many exceptions as rules.

In southwest Denver House District 1 rubs shoulders with HD-28 and HD-38. In northwestern Colorado, where you’ll find HD-26 sitting on top of HD-58. Why? The answer appears lost to the mists of time.

Speaking of the mists of time, though, until about sixty years ago, Colorado didn’t even use district numbers in the state House. Instead, counties just sent a designated number of representatives to the Capitol, based on their relative populations. It took a series of U.S. Supreme Court rulings in the 1960s to force Colorado to divvy itself up into state legislative districts, and to reliably update those boundaries every decade.

“We think of redistricting as something you do every 10 years consistently after the census,” Jackson said. “But that didn't happen until the sixties. Before that it was much more of a free for all.”

Jackson was kind enough to go back and look through old documents to try to find some answers, but said they were woefully bare of any rationale about how the districts ended up with their numbers.

(If you really want to nerd out on this kind of stuff, check out Jackson’s deep dive into Colorado’s redistricting and reapportionment history — which also explains why the process for redrawing political lines is ‘redistricting’ when it comes to congressional seats and ‘reapportionment’ for state legislative ones.)

What if a lawmaker ever wanted a specific number?

Finally, I wanted to know if lawmakers ever tried to exert pressure to get a certain district number; (After all, the human love of low numbers shaped the design of our license plates for decades.)

Jackson assured me that the Independent Redistricting Commissions were very careful not to take any consideration of incumbents into account. But she also acknowledged that lawmakers do get attached to their district numbers.

“Because they make yard signs and the yard sign has their district number on it and they have them all in their garage and they don't want to have to come up with a new yard sign for their next re-election,” she explained. “So yes, absolutely, they care very deeply about that. We didn't hear any complaints in the Redistricting Commission. They largely stayed out of it, but I can only assume that they did care.”

Whatever lawmakers may think of the number they landed with after the 2021 redistricting, term limits mean they won’t be around next time to worry about them shifting again. And as for Jackson, while she claims she’s always up for talking about redistricting history, she’s also been happy to get back to her day job on the legislature’s nonpartisan staff.

“I really liked redistricting before I actually worked on it,” she said.