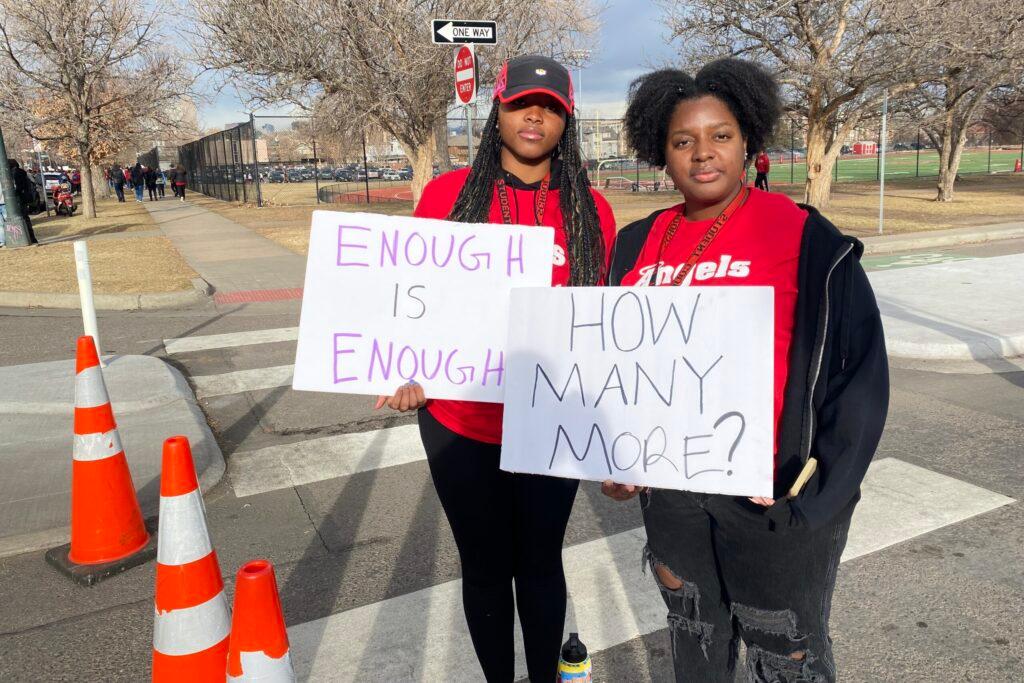

Hundreds of students marched outside Denver's East High School on March 3 to honor a fallen classmate, Luis Garcia.

He was shot recently just down the street from here and died two days earlier. He was 16 years old.

A huge bouquet of flowers sat outside at the entrance of the school as East Angel students wore T-shirts in red and white, the school colors, reading Angels Against Gun Violence.

The students soon marched to the Capitol, where they brought their message to lawmakers.

Alaijah Sims stood with a friend and held a handmade sign that read “How Many More?” The sign alluded to the fact that kids have been suffering at the hands of gun violence all over the country.

“But especially in DPS, we’ve had a lot of kids that have been injured due to gun violence,” Sims said.

It’s no secret that gun violence is an ongoing issue in America — lives have been taken through suicide, homicide, domestic violence, random shootings and mass shootings.

Johnnie Williams, executive director of a Denver youth program called GRASP, the Gang Rescue and Support Project, said he’d like to see more resources go to mental health for kids who are impacted by gun violence.

“I think the social impact of how and why these youth decide to carry these guns need to be addressed," Williams said. “How safe are they feeling in their social circles, how safe are they feeling in their neighborhoods or in the schools that they're attending.”

Beyond high-profile mass shootings, gun deaths have risen in Colorado steadily since 2008, according to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. State leaders and community advocates have worked to combat the issue for at least a decade.

Now Colorado is trying something new — a public health approach to gun violence prevention.

A new way

In a first-of-its-kind partnership, the Office of Gun Violence Prevention within the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment is teaming up with researchers from the Injury and Violence Prevention Center in the Colorado School of Public Health. They’ll create and maintain a resource bank of regularly updated and accurate materials regarding gun violence in Colorado.

In addition to the resource bank, officials at the new office also developed a grant program to fund evidence-and-community-based gun violence prevention initiatives. Grant applications opened in January and closed in February, according to Jonathan McMillan, director of the Office of Gun Violence Prevention. The grant program is awarding a total of $450,000.

More than 30 organizations applied in less than a month, McMillan said. Public health leaders said the partnership is merely the beginning of what they hope will lead to new community partnerships and access to resources.

McMillan said he believes this is a great time to initiate a project of this kind, as federal funding for gun violence research was previously limited due to the Dickey Amendment. For years it restricted the use of federal funds to advocate for or promote gun control. Congress has since clarified the bill to state that it does not prohibit federal funding.

“Now that it isn’t as big of an obstacle to funding research, we're going to be able to explore a lot of different techniques, methods, strategies and tactics towards reducing gun violence and in a way that is tangible,” McMillan said.

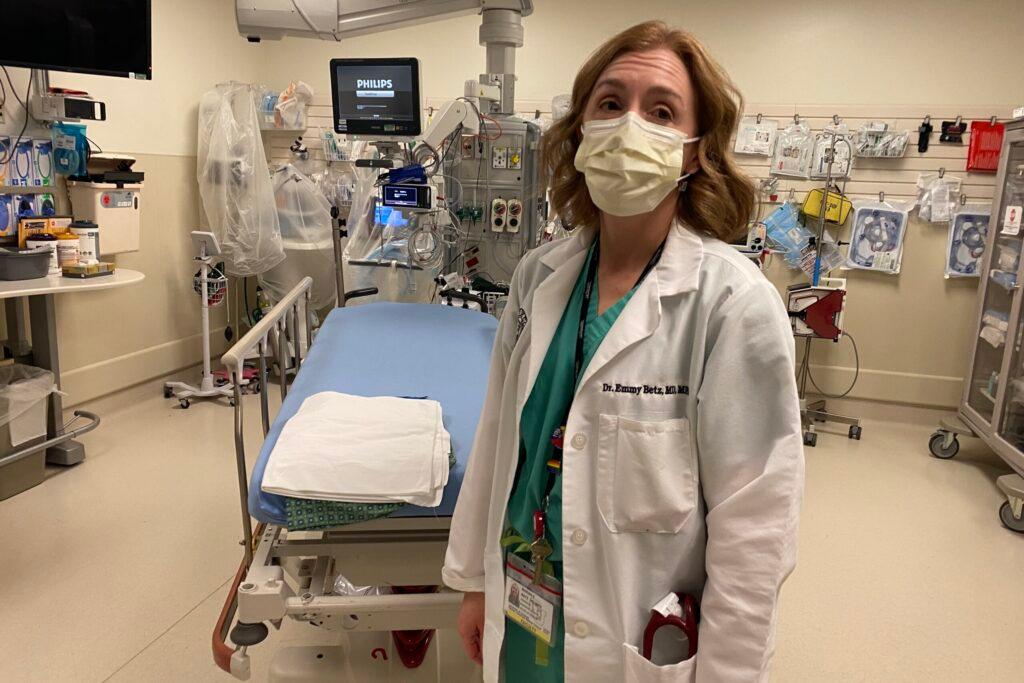

Dr. Emmy Betz, deputy director of the Injury and Violence Prevention Center at the Colorado School of Public Health, echoed the sentiments.

“When I was early in my research career, I had very well-meaning mentors say, ‘Don't do gun work, you're never gonna get funded,’” Betz said. “President Obama issued a memo clarifying that federal agencies could fund research. Since then, there's been additional targeted funding for firearm-related research from NIH and CDC.”

Public health officials said they hope to have the resource bank ready for a soft launch by late spring or early summer.

Impact of gun violence hits home

McMillan, 50, grew up in Northeast Denver in the 1980s and 1990s, and looking back, he remembers an increase in gun violence in urban neighborhoods that impacted young men of color. He said his lived experiences — witnessing gun violence and being incarcerated himself at one point has helped inform the work he does today.

“We were labeled as an endangered species, which meant we were less likely to graduate from high school, more likely to go to prison than college, and more likely to be dead by the age of 25,” McMillan said.

It was a wake-up call, but it was also the best thing that ever happened to him, he said, because he began making better decisions. He said he’s spent the last 22 years of his life working to help provide different opportunities for young people who don’t have access to certain resources.

McMillan said a friend of his was shot and killed in Denver while riding his bike.

He said that experience provided “evidence that life out here, as you know, at that time as a young Black man, was a vulnerable place, a dangerous place to be.

“That incident really is something that's going to impact them for years to come, and probably future generations who vicariously identify with that young man, with that young lady, with the mother,” McMillan said. “And then it becomes a community issue because everyone's grieving.”

As an ER doctor with UCHealth Emergency Care on Aurora’s Anschutz Medical Campus, Betz said she and her colleagues typically see a gunshot victim or two every day.

In 2012, the hospital treated victims after the Aurora theater shooting.

Betz said every type of shooting can leave lasting scars, visible and invisible.

“I don't wanna underestimate the emotional and psychological trauma, particularly for individuals who live in communities with this daily level of violence,” Betz said. “The psychological trauma from that is significant.”

Envisioning the work

So what does a public health approach to gun violence prevention actually look like?

According to Betz, it’s all about using the tools that are available.

“It’s such a big, horrible, messy problem and there's not one solution to it, which is really why we need a public health approach, which is grounded in understanding trends and then identifying at-risk populations, and then identifying what works to prevent injuries and deaths in those populations,” Betz said.

For example, some groups host gun lock giveaways to help prevent kids from getting into guns, Betz said.

“But how do we identify and assist at-risk teens and really jump in and make sure that they get into a better environment and how do we think about suicide prevention in older adults? There are all these different pockets that are gonna take different approaches, and that's what we're hoping to help the state figure out how to do,” she added.

McMillan commended Betz and her team for engaging stakeholders from all over the state to find out what the resource bank should and could be.

“We're going to be building a repository of all data that relates to gun violence in the state of Colorado that will have the data and the information about where we are seeing gun violence most often, what are the demographics which are most impacted.”

He said they plan to assess risk factors that are unique to certain demographics, too.

McMillan said he envisions the resource bank will be like the “Google of gun violence prevention” for the state of Colorado. Officials hope it will be a place where researchers, lawmakers and even the common individual can learn about what's happening in the state.

“If practical and if possible, it'd also be a place where people can convene to have productive conversations about gun violence and make those connections, collaborations and partnerships,” McMillan said.

At a recent meeting at the state health department building, McMillan fielded questions from community members about applying for grants to jump-start new programs.

Antonia Garza, a school social worker with the Denver Center for 21st Century Learning, said many students cope with gun violence every day. Others have posted images of firearms on social media, “posing with them. And so we're really trying to figure out what are some best ways we can support addressing this with our students.”

She’s optimistic about the new push.

“I think a hundred percent it can make a difference because we know that guns are going to be in our community,” Garza said. “And so we really need to work to educate our students, our families, and the community on how do we safely access them? How do we safely store them? How do we safely educate our students around them?”

Dominique Zimmerman is with a nonprofit startup called TenFour. It’s working with kids in Five Points, a historically Black neighborhood near Denver’s downtown. She said guns are readily available.

“It's a terrifying thought to think that the kids in these areas have access to things like that,” she said.

She said both the new data and grant money will be valuable to groups like hers.

“I've worked in public service for a while and having access to those resources really can make or break a situation,” Zimmerman said.