When Minister Glenda Strong Robinson of Longmont skipped class in 1968 to march with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., there were many things that she couldn’t have foreseen: That the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike she was supporting would become iconic in civil rights history. That Dr. King would be assassinated within days. And that 55 years later, she would receive a lifetime achievement award in his honor.

Robinson, a minister at Second Baptist Church of Boulder, was selected by the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Colorado Holiday Commission to receive this year’s lifetime achievement award. Her work in civil rights stretches back to her student days at Memphis State University.

“At that time I was just a 19-year-old junior trying to get through school, and I must tell you, the times were very tense, and it was scary,” Robinson told Colorado Matters as she reflected on more than five decades of activism.

Racial discrimination was omnipresent in Robinson’s life growing up in the Jim Crow South. Her father was called “boy” throughout his adult life. She remembers when she’d buy a candy bar after school, the store owner might immediately accuse her of stealing it. To this day, she said, she won’t leave a store without getting a receipt.

When Robinson enrolled at Memphis State, the university was still highly segregated, and she was one of only a few Black students living in her dorm. One professor made it very clear that Black students wouldn’t get a fair shake in his class.

“There was me and Willie Johnson in that class,” she recounted. “And this professor says, ‘I know that you people are probably the best and the brightest from your schools. You probably were valedictorian, salutatorian, whatever. But I can just tell you this, the most you can make in my class is a C.’”

It was against this backdrop that Robinson watched the Memphis sanitation workers go on strike for better pay and working conditions in 1968.

“I remember the spring like it was yesterday. Sleet, cold, icy, rainy,” she said.

The weather only made things harder for the city’s sanitation workers, who endured unsafe working conditions and earned less than $2.00 an hour.

“The way they were treated was inhumane,” said Robinson.

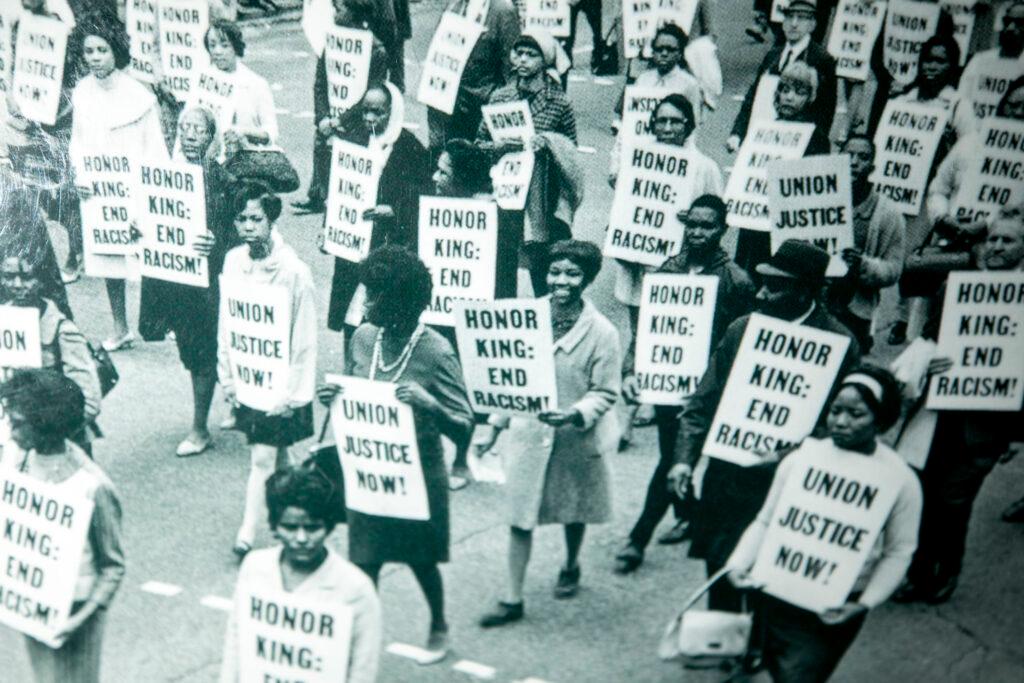

After two men were killed in a garbage truck compactor, the workers went on strike. On March 18, 1968, Dr. King offered his support in what became known as the “All Labor Has Dignity” speech. Ten days later, he led thousands of people, many wearing signs that read “I Am A Man,” through the Memphis streets. Robinson was one of thousands of students who skipped school to join.

As they walked, she sensed something ominous in the air.

“I just remember the rumblings. It seemed peaceful, and yet sometimes, you can have that eerie feeling that something is going on. I think everyone was a little bit nervous, because the mayor was threatening also,” she said.

Windows were smashed, the police moved in, and the day turned violent. Dr. King was rushed away.

“They started running up and down the halls cheering.” The day Dr. King was killed

A week later, Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis. Robinson heard the news from her white dorm-mates when she and her friends returned from dinner.

“They were just talking and laughing, and kind of cheering. And then, they came to us as we came into the door and said, ‘Y'all can have the TV.’ And we said, ‘Oh, what's going on?’ And then, they started running up and down the halls cheering, just screaming and just, ‘Yay.’ And then they said, ‘Martin Luther King has been shot and he's dead,’” Robinson said. “And then they said, ‘He got exactly what he deserved.’"

Days later, Robinson joined another march through the streets of Memphis, this time to memorialize Dr. King. She and others held signs that read “Honor King: End Racism.” A photograph of Robinson in that march hangs at the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

Since her days marching with Dr. King, Robinson has worked to promote civil rights. She serves on the executive committee of the NAACP of Boulder County, and conducts educational programs about Dr. King and civil rights. She’s currently advising the Museum of Boulder on an upcoming exhibit on Colorado’s Black history.

Robinson is only the second woman to serve as a minister at Second Baptist Church of Boulder. When asked how she remains hopeful in the face of ongoing racial injustice, she turned to a hymn.

“My hope is built on nothing less than Jesus' blood and righteousness. I dare not trust the sweetest frame, but wholly lean on Jesus' name. On Christ the solid rock I stand. All other ground is sinking sand," Robinson said.