Four years before a student shot and injured two administrators at East High and years before school safety was the No. 1 priority of parents, one Denver principal was raising the flag that something wasn’t right.

Before the 2019 school year had even started, Kimberly Grayson, the former principal of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Early College middle and high school, noticed students were already getting shot and killed in the community. It only got worse as the school year progressed.

She and her deans began compiling a list: shootings in nearby parks, school fights that faculty had to break up, guns at a homecoming dance, parents getting in a fight right outside the school office, teens from other schools entering the building and attempting to fight MLK students, students letting non-MLK students and gang members into the building, a student bringing a family member’s gun to school and passing it to other students, gang members from other DPS schools requesting to transfer into MLK, a drive-by shooting outside the school that hit a student.

“We cried, we begged, we pleaded for help,” she said last week as she shared a string of incidents that she said were ignored by district officials. “In fact, we asked for security to be stationed at the front door of our school because that's common at other high schools.”

She said the district, then headed by Susanna Cordova, refused. Grayson researched and requested a list of solutions such as security cameras and security wands. Most of them were denied. She felt alone and responsible to keep her students alive. She used money from the school’s budget to purchase 1,200 clear backpacks that were made mandatory for students. She paid for blinds for common area rooms with large glass windows.

“Safety and security was so lacking and we received no proactive support or preventive support,” she wrote in a 23-page document detailing multiple incidents of violence at her school. “I was trying to lead a building, provide safety in almost impossible conditions, and navigate traumatic events daily.”

Fast forward to this school year. The string of shootings at or near East High School brought attention that Grayson never got: the mayor, the superintendent, and the media — even the New York Times — attending press conferences on school violence. But breakdowns in security and flare-ups of violence in DPS go back years, with dozens of incidents happening at other Denver schools that don’t get the same kind of attention. Other school leaders and teachers, besides Grayson, have issued warnings as well.

“Some things could have been in place to prevent this mess (incidents at East High) from happening had people listened when we brought it up back in 2019. Because everything that East is going through, MLK brought it up to the district,” said Grayson.

In 2020, seventeen principals of middle and high schools voiced opposition to DPS’s resolution to eliminate school resource officers, arguing instead for a revision of discipline policies and academic structures in order to eliminate racial injustice. Former East High principal John Youngquist raised concerns and warnings about school violence in 2021 and made recommendations that were ignored.

Now, pressure is coming from multiple fronts for Denver Public School leaders and board members to respond.

Actions and reactions after the most recent shooting at East are varied: Students are asking for gun control and more security; principals want more say in whether they enroll students with violent backgrounds; everyone wants more mental health support; a new parents group wants a new school board.

And many believe the problem of gun violence in schools is much bigger than any single school district can solve.

A new group called Resign DPS Board has formed and it is circulating a petition demanding the resignation of all seven Denver Public Schools board members. It claims the board has failed in its obligation to keep schools safe and ignored repeated warnings from school leaders about school safety, according to the group.

That effort comes on the heels of the union for DPS principals calling for changes to how the district handles discipline. A letter recently sent to school leaders and DPS superintendent Alex Marrero makes several requests. The union wants a role revising the district’s discipline matrix that spells out what’s supposed to happen for specific student conduct. The principal’s union also wants more mental health support and new policies for enrolling students who have previous safety concerns. Finally, it wants protection for school leaders who raise safety and security concerns.

A group called Denver Families for Public Schools has released recommendations for moving forward, including reviewing gaps in the district’s threat assessment teams, collaborating with public health agencies for mental health services, and partnering with more community-based gang violence prevention programs that have a track record of disrupting violence.

The district’s community-led committee that advises the board also released recommendations for the long-term school safety plan the district must present, including recommending that the conversation around the plan be community-led, not district or board led.

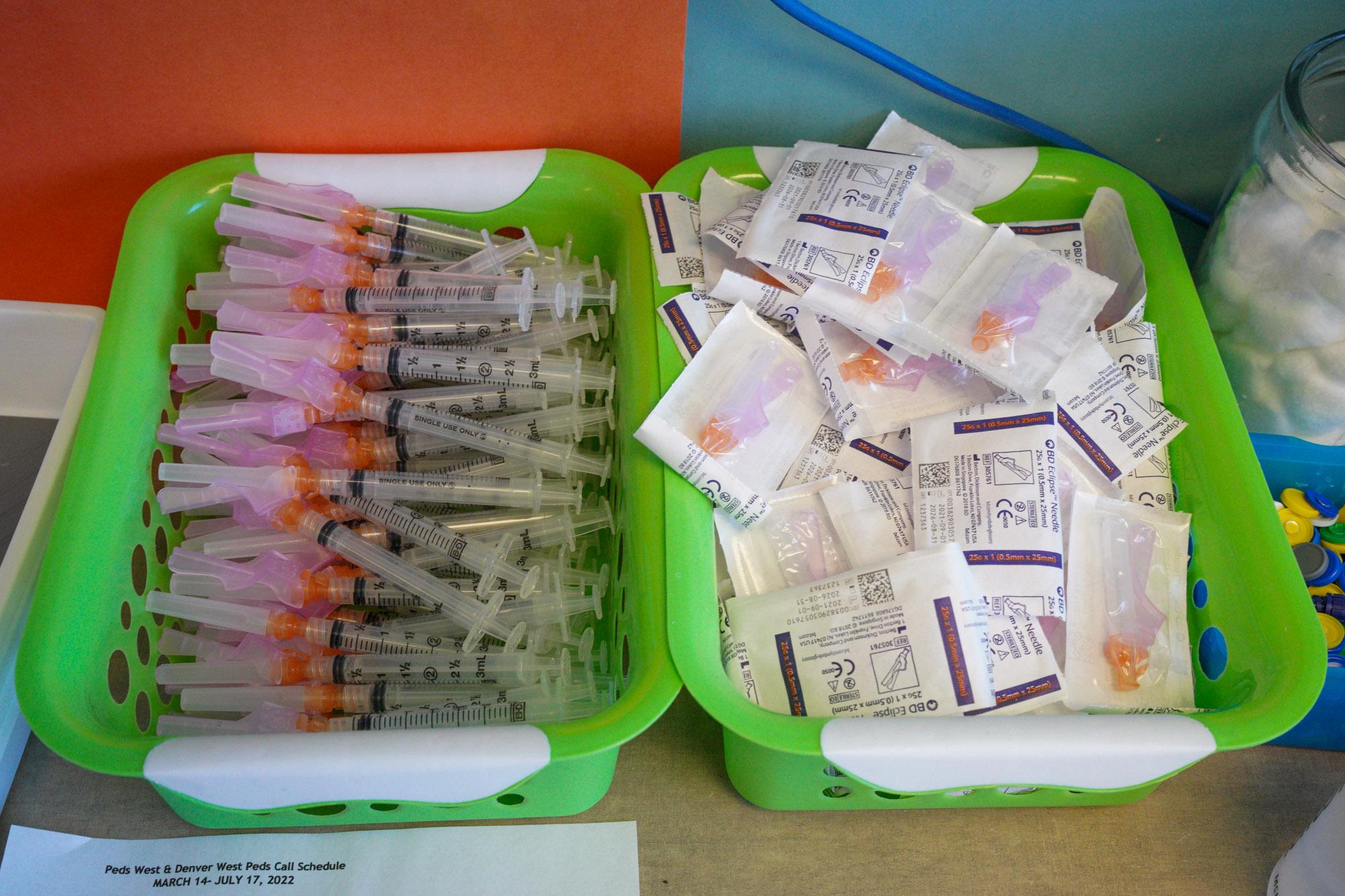

Superintendent Alex Marrero has until June 30 to present the plan. In the meantime, for the remainder of the year, DPS will be providing up to two armed officers and additional mental health staff in all high schools.

In a statement, Denver Public Schools said it will conduct a thorough review of board policies and other internal structures and behavioral standards.

“As a school district we are reviewing our disciplinary practices and looking for points of clarification and additional support we can provide to our students who may be struggling.”

The issue of why students are bringing weapons to school is complex and multifaceted.

It has roots in the collapse of systems of support, families, easy access to family weapons, social media trends — but also some argue, weak violence prevention systems at schools, including inadequate mental health and security support.

Some incidents in years past are consequences of well-intentioned efforts to break the school-to-prison pipeline. For years, data showed Black and Brown students were much more likely to be ticketed or arrested at school, eventually ending up in the criminal justice system. That led to the school board taking school resource officers out of DPS schools in 2020. But for years prior to that, schools have faced enormous pressure to keep disruptive or even violent students in school.

DPS places a huge emphasis on “disrupting bias and fighting disproportionality,” which means a child should be taken out of the classroom or school as a last resort, after receiving various interventions in the discipline ladder. The number of expulsions, classroom removals, and referrals to law enforcement have dropped compared to the 2010s, according to state data. Other incidents of violence are a result of spikes in gang activity and violence in surrounding neighborhoods.

More on the extraordinary pressure on schools to enroll students who some may see as potentially dangerous.

On Feb. 28, a student at Bruce Randolph High School reported to a school security officer that he had a gun, according to a police report. The 15-year-old said he was upset because he was being harassed online. When the officer tried to check his bag, the student ran. Surveillance video shows he stopped off in a room with a staff member whom he was close to. When the officer caught up to the student, the student didn’t have a gun on him. Later, the police returned to the school and a gun was found in the bag of Dante Quint, the school support staff member. The gun’s magazine was fully loaded. The man was arrested.

The student had served time in the Gilliam Youth Services Center and enrolled in Bruce Randolph earlier this year. He was on a safety plan, isolated in a room and provided with lessons there, according to school staff.

“They get searched when they're in the detention room,” said 10th-grade social studies teacher Doug Moehle. “They stay there all day, and they're not supposed to go to the restroom unescorted, but they're still in the building. And if the person who takes care of them that day isn't there, then it’s chaos figuring out, OK, now who's in charge of this student today?”

He said sometimes things fall through the cracks and a student goes where he’s not supposed to go. The student was back in school after the incident, which has some teachers on edge. When a student is found with a weapon, they’re supposed to be suspended for five days and then have an expulsion hearing.

“But there's nothing automatic anymore,” said Moehle. “It's like finding a loaded weapon is not enough to get a person expelled. And the way I understand it is when they're back in, or once the out-of-school suspension is over, then we are required to continue schooling them until the expulsion proceedings are finished.”

DPS hasn’t answered CPR’s questions about why certain students with criminal records are placed in certain schools. For students without disabilities, one former administrator said there is room for negotiation over students currently involved in a felony allegation that has not been fully adjudicated. They said a school can and should talk with the parents about what school might be the most appropriate. Another administrator said DPS central office pushed back if they tried to resist taking a student with a gun, assault, or rape charge.

Teachers say, behaviorally, this has been one of the hardest years ever.

Like the principal’s union, many teachers want the DPS discipline matrix to be reviewed. Following the matrix takes an extraordinary amount of interventions — each of which must be documented. Teachers are already overloaded and sometimes just give up. Several teachers have told CPR “there are no consequences” for students and students know that.

“We have nothing anymore that holds a student accountable,” said Moehle. “We don't have a dress code. We don't have after-school detention. If a student skips, all we have is a robocall that calls their family. And so students will skip a class, have no consequences, and they'll just keep doing it because nothing happens. Students run away from security and know that nothing's going to happen.”

Everyone agrees that the system — not just the school system — is not getting troubled kids the support they need before and after tragic incidents.

“Schools are not to blame for the increase in violence and cannot address the issue of gun violence and safety alone,” stated the DPS principal’s union.

It is also calling for legislation to keep weapons out of the hands of minors, increased funding for schools for mental health support and support for parents to minimize the impacts of trauma. DPS, for its part, says it is looking forward to building partnerships with the police department, mayor’s office and community groups in addressing gun violence.

Moehle however, believes more students are reporting what they see and hear.

“The fact that so many guns are getting found before something happens, I think that's a positive sign that the structures we have in place to report these are working.”

Funding for public media is at stake. Stand up and support what you value today.