This story was originally published by Chalkbeat. Sign up for their newsletters at ckbe.at/newsletters.

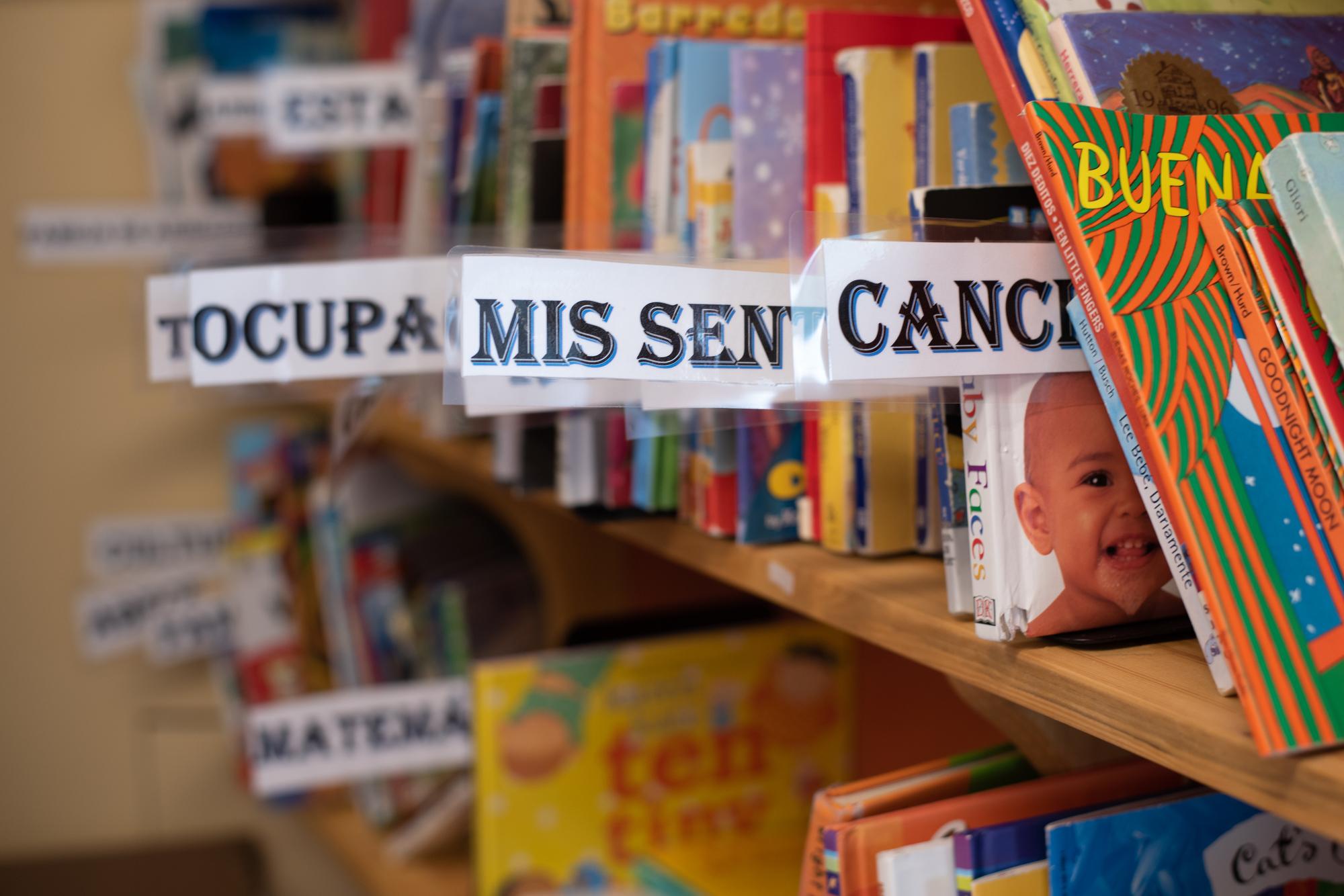

Every morning, students in the Early Excellence Program in north Denver start their day with a song in Spanish and English. Story time and reading circles also happen in the two languages. Kids are encouraged, but never forced, to speak both.

These are some of the ways teachers at this highly-rated preschool try to give students a strong foundation in their home language as they prepare for school — something researchers agree is helpful for young bilingual learners.

As the state prepares to roll out universal preschool, a new taxpayer-funded program starting in the next school year that offers preschool hours for free to all 4-year-olds and some younger children, officials have given priority to children who don’t speak English at home. The state will offer those children more hours of tuition-free preschool and is promising — for the first time — that programs will need to use teaching strategies proven to help multilingual learners.

But with the launch just months away, big questions still remain about whether enough is being done to get the word out, what programming will look like, and what help providers will get to improve their offerings.

Early Excellence leader Jennifer Rodriguez-Luke says the families she works with are confused about how to apply or if they qualify. She has assigned a staff member to help them through the process, but has had limited success in getting new applicants.

So far, the only preschoolers that appear will match to her program are the ones it already serves, who they have helped walk through the application.

“For a level 5 in the heart of Denver, we were hoping to at least have 10 new students,” Rodriguez-Luke said.

She’s worried it means vulnerable families across Colorado may not be applying for universal pre-K — and may miss out on learning that has been shown to set children on the path to educational success.

Under Colorado law, 4-year-olds identified as English learners are eligible for additional hours of preschool. The additional hours — 30 instead of 15 — are dependent on state funding. The state first has to make sure it can cover the cost of some preschool for all 4-year-olds who apply. Three-year-old multilingual learners can qualify for 10 hours per week of free preschool.

English language learners are among the children who could most benefit from preschool, which is one of the reasons these students are eligible for more preschool hours.

But in the current school year, only 29 preschool students statewide are currently identified as English language learners, according to data provided by the Colorado Department of Education.

Although it’s unclear what the new system will look like this fall, creating a process to identify multilingual learners and establishing standards for how they are taught will be a benefit for students, even if it’s still a work in progress, researchers say.

“You’re trying to create a system that I don’t even know is there,” said Guadalupe Díaz Lara, assistant professor in the Department of Child and Adolescent Studies at California State University. “If we’re thinking of these investments, why don’t we do it in the way that’s the most high quality for kids?”

Colorado leaders have rushed to set up new universal pre-K, which will replace a smaller state-funded preschool program for children from low-income families or who have other risk factors.

But even as applications opened in January, critical parts of the program are still not in place.

The law that created universal preschool also directs the new state department to establish quality standards that participating preschool providers will have to meet. Those will include standards on identifying, testing, and serving students who are dual language learners. But those standards haven’t been created yet.

Previously, under various state and federal programs for preschool age children, providers followed different rules for educating the youngest English learner students. Preschool, unlike K-12, has had no consistent requirements for identifying children in need of language support and no standards for how they should be taught.

The state’s new department overseeing the rollout of universal preschool has not been able to provide numbers on how many children so far enrolled for the fall checked the box indicating limited English proficiency. Officials say they are asking each provider to speak to families to verify that parents correctly checked those boxes.

A different way to screen students may be required eventually. It’s one of the requirements the law lays out for universal preschool.

When families, including those who indicate their child has limited proficiency in English, apply for universal free preschool, they can search providers and list their top choices. They can also search providers and learn which have bilingual staff or programs. The online application is available in three languages: English, Spanish, and Arabic.

The matching process will prioritize a family’s preference, regardless of whether that program has bilingual staff or programs. That means providers who have not previously been expecting to serve this population of children could end up with students enrolled identified as English learners. Depending on what standards are created, they may have further to go to meet the children’s needs.

State leaders say preschool providers will not be allowed to deny a child a spot because of language proficiency, but recognize that some won’t be prepared right away.

While much of the system is still being created, the infrastructure for English language learner students is furthest behind because research, standards, and practices have previously been limited.

Dawn Odean, the state’s universal pre-K director, said the state creating a system from nearly nothing represents opportunity.

“We do have a unique opportunity here to make more significant gains in the multilingual environment,” Odean said. She wants the department to help providers, she said, and won’t penalize them for not immediately meeting the standards.

“We can make it an act of compliance but that’s not what’s going to serve students well,” Odean said.

Instead, Odean said, the department will focus on helping all providers improve.

Ana Paola Burrola Bustillos has two kids in Jeffco, including a 4-year-old enrolled in preschool at Foster Dual Language PK-8. She said she didn’t know the state was rolling out free universal preschool, and thinks it’s a good thing even though her daughter, who is moving on to kindergarten this fall, won’t benefit.

Burrola Bustillos said she likes Foster for her children because she believes they’ll benefit from being bilingual.

“I feel that if they can learn in both languages they’ll be better off when they’re older, in everything, in communicating with other people, in their jobs, in everyday life,” Burrola Bustillos said.

Patricia Lepiani, president of The Idea Marketing, said her group was contracted in January to market universal preschool, just days before the application opened.

Lepiani said that 25 percent of the $527,000 marketing budget is dedicated to reaching non-English speaking families — a larger percent than most projects would allocate, she said. In Colorado, Lepiani estimates, 21 percent of the state population speaks Spanish, though not all are monolingual.

The fastest thing to set up, she said, were social media ads, and later some banners that were set up at local dentist offices and shops such as the Carniceria/Mercado Los Dos Toros in Denver, the Panaderia Contreras in Denver, and Ay Wey Snack in Aurora.

The large banners say “Medio día de preescolar gratis para todos los niños de Colorado” — “Free half-day preschool for all Colorado kids” — and include a QR code and a link to the state’s preschool homepage. A smaller Spanish-language poster notes that kids who start kindergarten unprepared tend to stay behind and urges parents to “make sure your kids are ready.”

The budget wasn’t enough to cover any radio or television ads, Lepiani said.

The larger campaign Idea Marketing has planned includes having community navigators and ambassadors trained to help get the word out and help families fill out the application. That part of the work launched mid-March. Among the organizations they’re partnering with are Latinos Unidos of Greeley, The Rocky Mountain Welcome Center, and Padres Adelante Family Services.

The focus is also on educating families on the importance of preschool.

“We have been doing everything we can as fast as we can, in the smallest amount of time,” Lepiani said. “The deployment of boots on the ground across the state takes a bit more time.”

Part of the work needs to be reaching out to community leaders to get the message to families about why preschool is important and about how their children can be supported, Díaz Lara said.

In California, many of the families Díaz Lara works with mistakenly think that putting their children into bilingual programs might confuse them and lead to developmental delays. But home language support can benefit students, she said, and preschool staff just need to know how to support that development.

At Early Excellence, where a staff member helps walk families through the application, some families think they won’t qualify because they think they make too much money or are already bilingual and don’t consider their children to have limited English proficiency. Some who are undocumented or have mixed immigration status are unsure if they are allowed to apply.

“It’s already scary to get on a website and give so much information,” Rodriguez-Luke said. “We just don’t want them to get lost in the system.”

So now, Rodriguez-Luke is working on also translating the school website into Spanish, hoping to put out more information, and offering an open invitation to help walk families though the application for free preschool.

More studies are necessary to identify the best strategies to teach multilingual preschool students, researchers say, but some things are clear.

“Being bilingual is not enough,” said Cristina Gillanders, associate professor in early childhood education at the University of Colorado Denver. “You have to have the preparation to teach these children. You have to understand bilingualism and how bilingual children learn languages.”

Some preschool providers that serve children who don’t speak English do focus primarily on having bilingual staff to help.

Joe Ziegler, education director at The Family Center/La Familia in Fort Collins, which serves a primarily Spanish-speaking population, said his program for children from six weeks old up to age 5, isn’t officially bilingual based on his curriculum, but he’s focused on hiring diverse and bilingual staff. About 50 to 70 percent of the young students start off only understanding Spanish.

When the program first started, he said, the school often had to rely on older siblings to help staff communicate with families. They’ve since been able to move away from that by hiring more bilingual staff, and now the focus is on making sure all staff understand inclusive best practices.

“We’re more intentional now,” Ziegler said. “There’s more of an emphasis now on understanding what a family and a child’s experience is.”

In Aurora Public Schools, preschools have long been using a test to identify how students progress in their acquisition of the English language. The district says 54 percent of the district’s 2,100 preschool students are English language learners.

Researchers say traditional tests used with older students are difficult to administer to 3- and 4-year-olds who may not be able to sit still long enough, use a computer, or hold a pencil.

Cynthia Cobb, the early childhood education director for the Aurora district, said the test teachers use in Aurora preschools aren’t sit-down tests. Teachers observe students in the classroom to track progress in many areas, including language skills.

“Young children are usually terrible test-takers. Their development is fluctuating all the time,” said researcher Gillanders. “In order to have a much more complete picture of the child’s development, you have to be with them for a longer period of time.”

That’s why teacher training to understand what they’re seeing in children is key.

Cobb said the Aurora district strongly believes that being able to identify and support students is a benefit. And, she said, students are more likely to eventually be proficient in English when they begin education in preschool.

While there may be changes preschool providers need to make, Cobb said it should all be for the best.

“It’s a learning process,” she said.

Ziegler knows the standards the state is likely to create for educating students like his will probably include additional training for staff, which he knows can be a good thing, but he said that accessing additional training for his staff has been a challenge.

He has partnered with the local school district to do some professional development for his teachers around supporting students who might not yet understand English. But when teachers seek out additional classes themselves, many are only offered in Denver, about a 90-minute drive away.

Other staff, who primarily speak Spanish, struggle to find classes offered in Spanish. Ziegler said his center is working with a community college to try to develop some classes for staff that can be offered in Spanish.

“In our community, I don’t really see those resources,” Ziegler said, who believes a universal pre-K program will eventually be beneficial. “But right now, it’s very stressful. We’re building the plane as we go.”

Yesenia Robles is a reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado covering K-12 school districts and multilingual education. Contact Yesenia at [email protected].

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.