Unite for Colorado, one of many groups spending “dark money” to influence Colorado elections, has won one of its legal battles with Secretary of State Jena Griswold’s office.

The state office is trying to force Unite for Colorado to pay fines and reveal the identities of its donors. But a judge ruled that it has not run afoul of the state’s transparency laws.

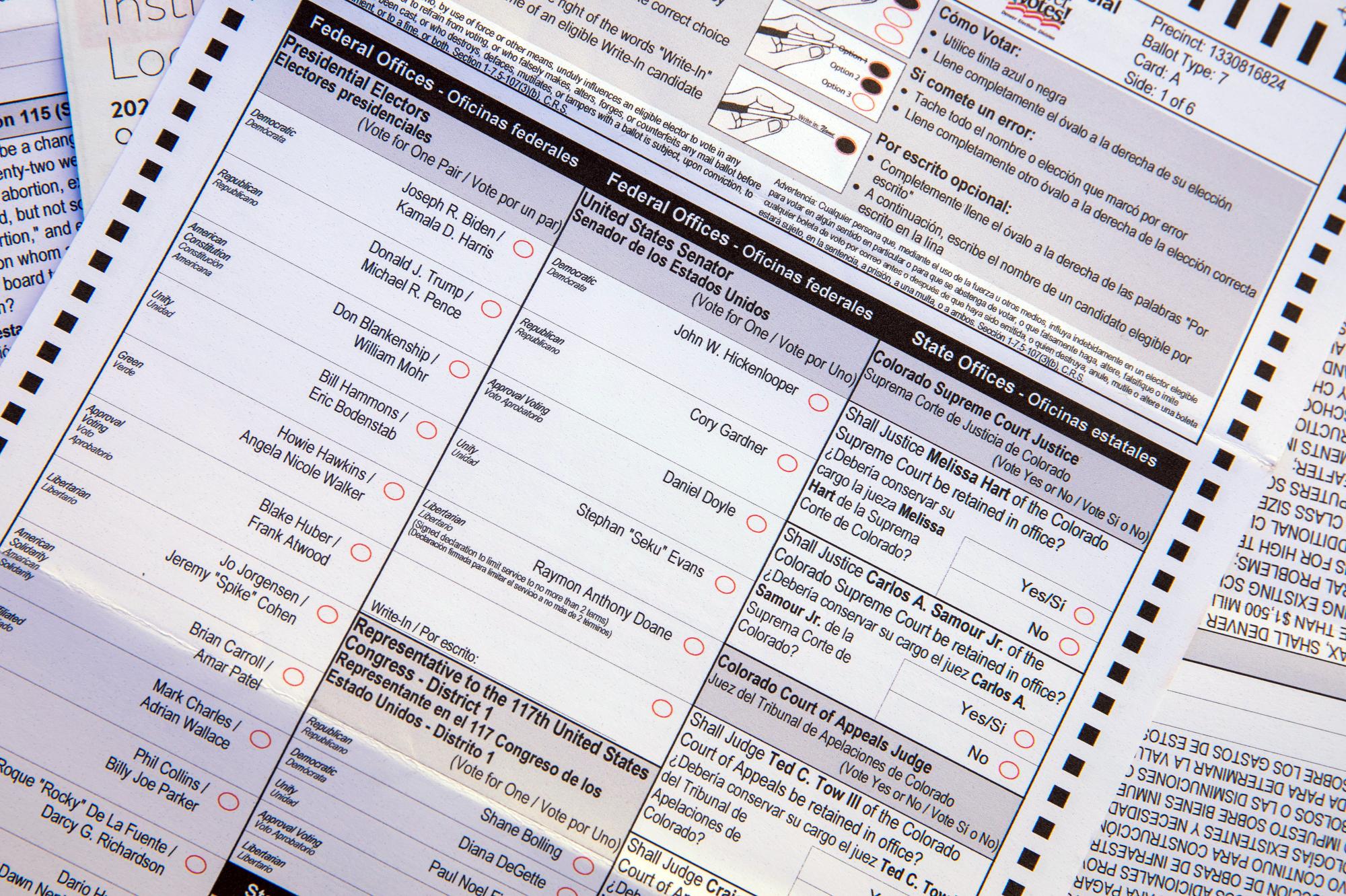

The case dates to the 2020 election, when the group spent about $4 million on three different ballot initiatives. The Secretary of State’s office argued that because the group spent that much money, it should have to register as a political committee and file finance reports.

As a 501(c)(4) nonprofit, Unite for Colorado is exempt from campaign finance laws, allowing it to raise and spend more money while keeping its donors secret. But to qualify for those privileges, it has to ensure political activity only makes up a certain portion of its overall spending, according to state and federal law.

The state's case against Unite for Colorado

At issue in this case was language in the state Constitution, which says a group must register as a political committee and report financial details if it has “a major purpose of supporting or opposing any ballot issue or ballot question.”

State officials argued that spending millions of dollars on signatures and political advertising was “a major purpose” of the group. The Secretary of State’s office fined the group $40,000 and ordered it to reveal its donors in Dec. 2021. The case eventually went to court.

“This new organization … had no longstanding involvement in Colorado politics,” reads a Sept. 2022 filing by Attorney General Phil Weiser’s office.

The filing continued: “But by the November election this newcomer had spent over $4 million on ballot issue advocacy. Money that went to shaping voter attitudes on fundamental issues like how Colorado funds its government, and how the state allocates its electoral college votes for U.S. President.”

Unite for Colorado, a nonprofit, argued it didn’t trigger the reporting requirements. While it spent about 23 percent of its 2020 budget on ballot initiatives, that money was spread across multiple ballot measures. It didn’t spend more than 9 percent of its total budget on any single measure.

Therefore, the group argued, its “major purpose” was not to support any single ballot measure. Judge David Goldberg agreed.

“The statute at issue uses the letter ‘a’ in defining a major purpose and the term ‘ballot question’ – not the plural or an aggregation of expenditures on several or all ballot issues or questions,’” wrote Goldberg, a Denver district judge.

But Goldberg’s ruling isn’t the end of the road. The state still can appeal Judge Goldberg’s ruling. There’s also another legal battle over Unite for Colorado’s spending on the 2021 elections.

“The Secretary of State’s Office is reviewing Judge Goldberg’s ruling and discussing the matter with the Department’s legal counsel at the A.G.’s office,” wrote Annie Orloff, a spokesperson for the Secretary of State, in an email to CPR News.

Unite for Colorado's work in local and state elections

Unite for Colorado has supported a range of conservative causes. In 2020, its money backed Proposition 116, which asked voters to cut the state income tax, and Proposition 117, which gave voters new authority over the creation of fees; both measures passed. The group also spent seven figures to oppose the state’s involvement in the national popular vote effort. That measure still passed.

It also has spent millions of dollars to support a network of conservative groups and candidates, as The Colorado Sun reported. Its director at the time of the 2020 spending was Dustin Zvonek, now an Aurora city councilman.

The group argued it was being singled out by Democrats in the Secretary of State’s Office because of its politics. Liberal-leaning groups similarly have used dark-money protections to spend large amounts of money from anonymous sources.

The state legislature recently tried to settle these kinds of questions more definitively. A new law sets much firmer standards for independent expenditures. SB22-237 says that a group like a nonprofit only has to register if it spends more than 20 percent of its budget on a single ballot issue, or 30 percent on ballot issues generally, over a period of three calendar years.

Under those standards, Unite for Colorado would have been in the clear.