Editor’s Note: CPR News has spent months talking with teenagers, parents, doctors, advocates, political figures. We’ve looked through once-secret internal industry documents released by tobacco companies and listened to many hours of city council and legislative debate. What we found is that the conversation about tobacco products, especially flavored ones like menthol, is not only about nicotine’s deadly effects or the impact on local economies. It’s about ethics, optics and equity.

On a recent sunny Thursday morning, a group of high schoolers gave presentations on issues that have touched their lives. Racial bias, guns and gentrification were topics that the students, mostly juniors and seniors, talked about to an audience of teachers, parents and guests who’d gathered at Manual High School in Denver’s historically Black Five Points neighborhood.

One of the students, Tekyra Miles, a senior and vice president of the Black Student Alliance, listened intently and in agreement with all of the timely issues that were discussed, but she would add one thing to the list.

“Vaping is very common within students and just peers that I know inside and outside of school,” she said. “I think it’s just a thing to do.”

In recent years, young people in Colorado have taken up vaping, rather than cigarettes, with one in six high school students classified as current users.

Miles doesn’t smoke or vape. “I just don't wanna get addicted,” she said, adding, “I think some of us realize that it is a social justice issue.”

She knows all too well the dangers of cigarette smoking. Her grandmother Patricia had been a longtime smoker. Though Patricia had quit, she was hospitalized with health problems related to smoking.

“She got put in ICU and they kept on saying, like, ‘your lungs are failing, like your lungs are failing,’” Miles said. “And I think if she didn't smoke, she would've came out of the hospital alive.” Patricia was in her early 60s.

Her grandmother’s preferred choice was Newport, a menthol cigarette, made by R.J. Reynolds, the country’s second-largest tobacco company.

Tobacco corporations have exacerbated existing health disparities by directly marketing flavored tobacco products to communities of color — including in Colorado. That historic targeting has made tobacco consumption hard to resist, meaning that where you live, and what race you identify as, are more likely to lead you down a road to long-term health problems.

The leading cause of preventable death

Colorado sees itself as one of the nation's healthiest states, but about 5,000 Colorado adults die from smoking-related illnesses each year. And the state spends more than $2 billion annually on health care costs for illnesses caused by smoking.

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable death and disability in the U.S. according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Every year more Americans die from smoking than murder, AIDS, suicide, drugs, car crashes, and alcohol, combined. A federal court ordered tobacco firms to post that information on their websites, in advertisements, and beginning July 1, 2023, in locations where tobacco products are sold.

The adverse health effects cut across race, ethnicity and socioeconomic background. But Black and Hispanic Coloradans, as well as Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander and multi-racial residents, are all far more likely to smoke than white Coloradans, according to the state health department. And smoking only adds to other chronic health disparities, such as depression and obesity.

White Coloradans also live years longer than Hispanic and Black residents. And in many diverse communities, those gaps can be stark.

“The average life expectancy for people living in some Denver neighborhoods is as much as 12 years lower than that of people living in adjacent neighborhoods,” said Dr. Rocio Pereira, who directs Denver Health’s Office of Health Equity.

The issue is timely. The Food and Drug Administration has been weighing a controversial proposal to ban menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars. That ban could hit a third of cigarettes sold, representing $20 billion a year in sales, according to the Wall Street Journal.

For their part, tobacco companies argue menthol cigarettes don’t pose any greater risk of smoking-related disease than non-menthol cigarettes, dispute whether bans on flavored products impact cigarette consumption and warn banning products often leads to unintended consequences, like a spike in illegal and unregulated products flooding the market.

'It’s the menthol'

For Tekyra Miles, menthol cigarettes have been around her for most of her life. Her father, Lawrence Miles Sr., began smoking decades ago.

“Actually growing up as a teenager, I didn't know nobody who did not smoke,” he said. “I've smoked Newports probably for the last 27 years.”

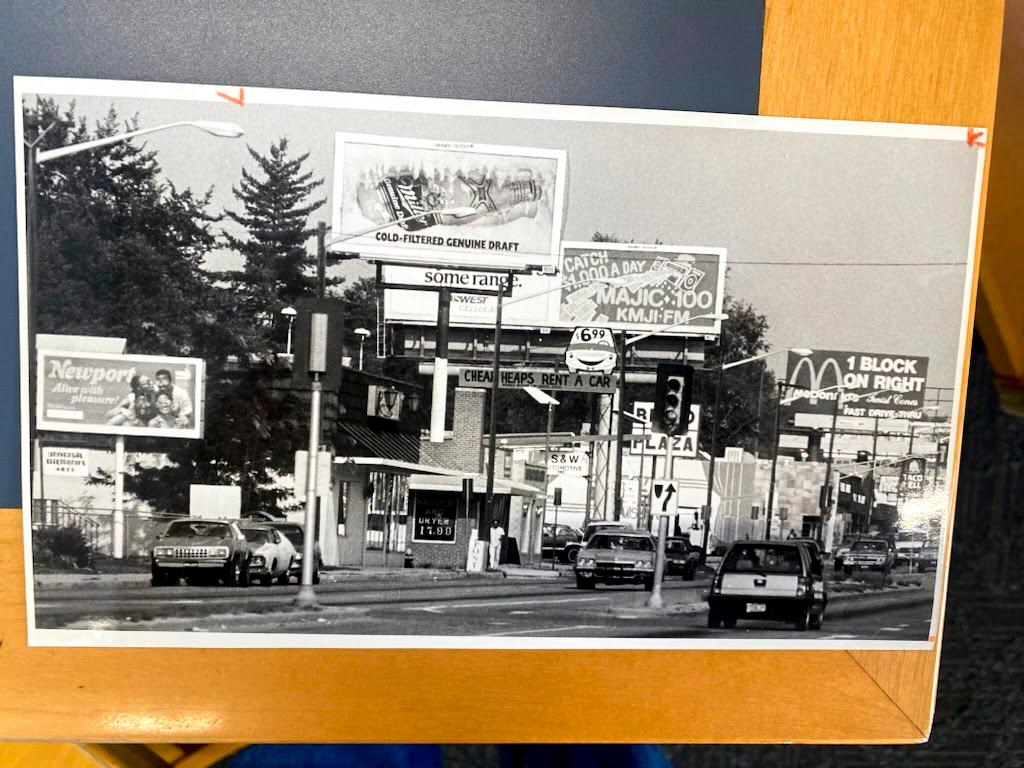

He remembered a lot of Newport ads on billboards, in magazines and newspapers.

“They were advertising. They were everywhere down here. They were the cheapest ones. So they knew that that was what we can afford,” said the elder Miles, who works at a factory that makes potato and corn chips. He also runs a barbecue food truck with his wife, Tekeysha Thomas.

Thomas said she’s smoked Newports since her days attending East High. Together, the couple developed a pack-a-day habit, she said.

“That's just what everyone was smoking and has gotten everybody addicted to,” she said. “It's the menthol.”

Tobacco companies developed the cool, minty menthol flavor to ease the harsh feel of cigarettes, making smoking easier to start. In the 1950s, less than 10 percent of Black Americans who smoked used menthols. After TV ads for cigarettes were banned in 1971, the Newport brand and others targeted Black neighborhoods with slick billboard and print ads for decades. Now more than 85 percent of Black smokers smoke menthol.

'Selling the ideal of cigarettes'

In Denver, it was Black and Hispanic neighborhoods that the tobacco industry often targeted with widespread advertising and other tactics.

The proof can be found in the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents, an archive of 15 million documents that were released as part of a multi-state legal settlement. Type in “Colorado” or “Denver,” and pretty interesting stuff pops up.

Like in 1981, when President Ronald Reagan came to Denver for an NAACP convention. There, companies like Brown & Williamson handed out hundreds of sample packs of free cigarettes with names like Kool Kings and Viceroy 100s.

Another document from the ’80s shows Brown & Williamson, which later merged with R.J. Reynolds, picking out a number of specific Denver locations for billboards for cigarette brands marketed to communities of color. One billboard was placed in north Denver at East 47th Avenue and Colorado Boulevard, a busy intersection near Interstate 70. The document describes it as a “dense Black neighborhood” on the way to the airport.

Several locations referenced are in and around the Westwood neighborhood, in southwest Denver. The document calls them “dense Spanish,” as in Hispanic, neighborhoods.

The document notes a demographic factor in the placement of the billboards: “considering the Hispanics as 26% and Blacks as 10% of the total population.”

The push was all about “selling cigarettes and selling the ideal of cigarettes to Black kids,” and Latino youth, said Princeton professor Keith Wailoo, author of “Pushing Cool, Big Tobacco, Racial Marketing, and the Untold Story of the Menthol Cigarette.”

“The way in which menthol smoking became entrenched in poor communities, in Black communities, is by design,” Wailoo said.

Wailoo examined the industry’s practices over a century, revealing “how the twin deceptions of health and Black affinity for menthol were crafted — and how the industry’s disturbingly powerful narrative has endured to this day.”

The companies influenced “buying habits and racial markets” nationwide, with menthol flavoring at the heart of their advertising strategies They hired tobacco marketers, consultants, psychologists and social scientists. They sponsored events, like Kool Jazz festivals.

Wailoo said the marketing campaigns often employed “hidden persuaders,” such as community leaders, Black lawmakers and civic groups, including the NAACP.

In Colorado, Wellington Webb, Denver’s first Black mayor, a Manual High graduate, and prominent Democrat, has worked as a consultant for tobacco giant R.J. Reynolds. In 2021, he opposed a ban on flavored tobacco, including menthol, in Denver.

The late Ruben Valdez, the state’s first Hispanic House speaker, also a Democrat, and key figure in west Denver politics, also lobbied for tobacco companies after leaving office. A contract in the records of Philip Morris from 1996, found in the online database, shows Valdez was paid a $35,000 retainer that year for consulting and lobbying.

Wailoo said it’s part of the tobacco industry playbook. The hidden persuaders are “not really speaking for the health and well-being of Black people,” and other marginalized groups, he said.

“They are entangled with the industry, and that's part of (the tobacco companies’) strategy,” Wailoo said. “They are influencers.”

In an email to CPR News, a R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company spokesperson said, “Reynolds is and has been committed to the responsible marketing of all of its products, including menthol cigarettes. Our advertising has historically included a wide range of demographic groups, including African Americans, reflecting the diversity of our adult consumer base.”

Philip Morris/Altria, which makes the Marlboro brand, did not respond to a request for comment before deadline.

Last month, Colorado entered a settlement with Juul, the e-cigarette manufacturer, which Altria had invested billions in until severing ties this year. Juul used enticing flavors and unscrupulous marketing tactics that helped set off an epidemic of teen vaping nationally and in this state.

'You wanna be those people!'

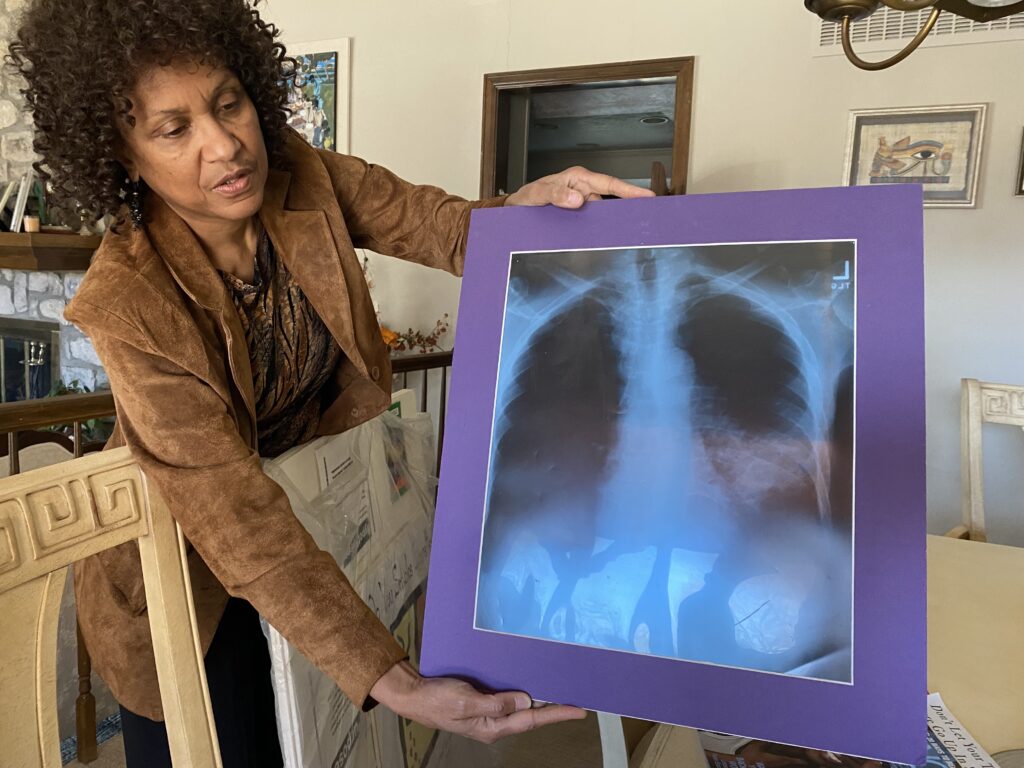

Dr. Terri Richardson, a retired Denver primary care physician, who worked at Denver Health and Kaiser Permanente, has tracked this issue for years. At her home in Aurora, she pulled cigarette ads from old issues of Ebony and Jet magazines.

“These are cool people. Look at that. I mean, you wanna be those people!” she said, holding up an ad with a smiling Black couple on a dance floor, with Newport cigarettes in hand. The words “Fire it up!” and “Newport pleasure!” appear in orange copy on a green background.

In the mid-1990s, Richardson did a community survey and found tobacco billboards and signs were prominent in three diverse Denver neighborhoods — Five Points, Colfax Avenue from Broadway to Glencoe Street and Southeast Denver, near George Washington High School.

That kind of normalized messaging proved persuasive and had a lasting impact.

In visits with patients who smoked, Richardson would ask them what they used. The common choice were menthols. She saw the outcome of that smoking.

“We saw a lot of heart disease, saw a lot of cancers,” she said.

Black Americans have the highest death rate and shortest survival rate of any racial or ethnic group in the U.S. for most cancers.

In 1997, Richardson wrote a study that looked at the connection between smoking menthol cigarettes and respiratory and digestive tract cancers in Black people. The study was saved by one of the tobacco companies and later surfaced in the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents.

Richardson now works with the Colorado Black Health Collaborative. It’s exploring ways to help people quit, including through the Menthol Tobacco Knockout, which aims “to raise awareness, to educate and take action against the predatory marketing of menthol tobacco products in our community.”

“We know it's harder to quit once you start menthol. So once people are addicted, then you have lifelong smokers,” Richardson said.

'The luxury of growing old'

Back at Manual High in Denver, Lawrence Miles Sr. said he has a recurring cough and, years ago, had a lung collapse and a stroke. He and his wife, Tekeysha Thomas, are now trying to quit smoking.

“For our grandkids, our kids, and just ourselves,” Thomas said. She knows it will be hard to overcome the addiction.

Miles has been cutting back on smoking lately. “Cigarettes is a killer,” he said. “I don't want them around me anymore, you know, and around my family or anything. I can definitely feel myself getting better health-wise.”

Their daughter Tekyra is just a few short weeks away from graduating, looking forward to college and possibly a medical career, where she’d bring a focus on health equity.

“I feel like young Black women and young Black men should have the luxury of growing old,” she said. ”And we don't really have that luxury.”