In 2019, Pueblo voters elected their first mayor in more than 100 years. For much of the previous century, the city was run by a city manager.

Supporters of the move to a mayor said it would provide clear direction and modernize the city’s form of government with a strong executive. Detractors didn’t want the switch, and valued having a public servant that served at the pleasure of and was accountable to what they believe is a more democratic form of elected leadership — the city council.

The people against the move never really have gotten over the switch, and just a few years later have been pitched in battle with the city’s government over whether they should return to their former system — administered once again by a city manager.

Along the way, there’s been bitter fighting, arguing and name-calling, failed ballot petitions and, finally, threatened lawsuits to settle the matter.

On Monday, Pueblo’s City Council voted down a proposal to put the change to the city’s form of municipal government up for a special election in August. The measure would have given voters the chance to oust the community’s current “strong mayor” system — in place since 2019 — and return to a city manager form of government.

It was the latest salvo in a months-long effort from opponents of the current system, who are accusing the city and current Mayor Nick Gradisar of obstructing their efforts to hold a public vote through the petition process.

Those opponents, which had been exploring legal action against the city, now say they are holding off amidst the council vote.

A strong mayor

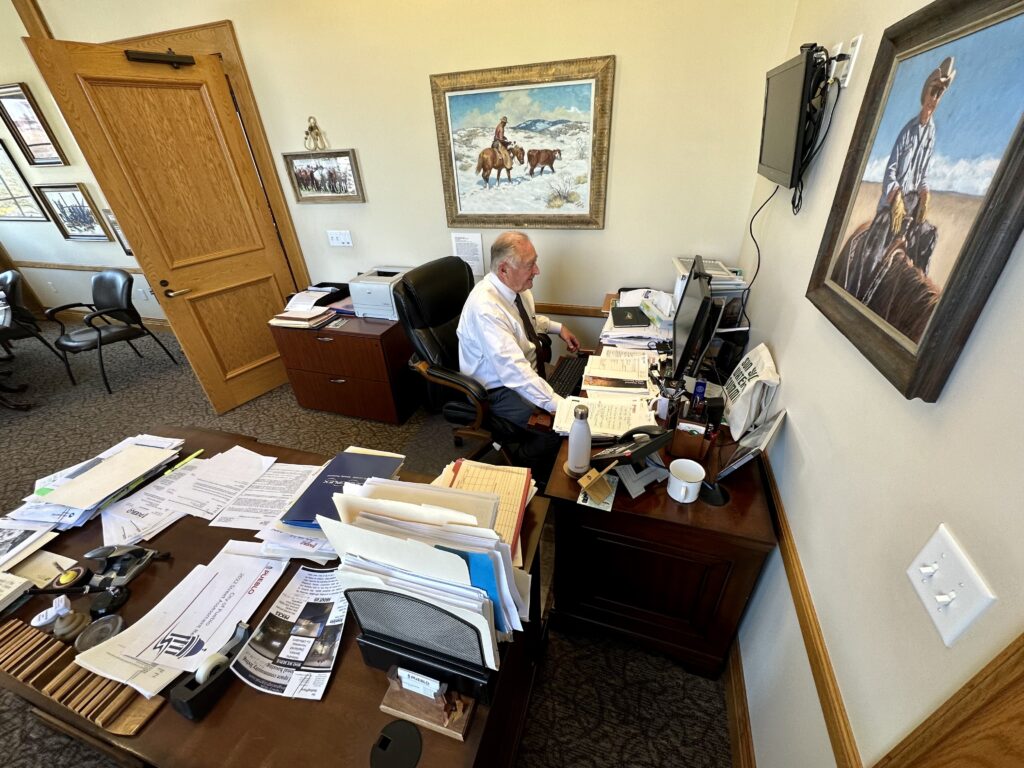

When Pueblo voters approved the switch to a strong mayor form of government, it was a particular victory for Gradisar. The Pueblo native and longtime local lawyer and Democratic political operative had been working to convince his community of the merits of Denver’s municipal system of government for well over a decade.

His advocacy had led to a public vote on the strong mayor idea in 2009, where it was defeated by a 2 to 1 margin. However, Colorado Springs voters approved the change just one year later.

“I saw what was happening with the city manager system and the fact that there was nobody in charge,” Gradisar said in a recent interview with CPR News. “We weren't getting our share of the growth that other parts of Colorado [were] getting.”

By 2017, growth in Pueblo was stagnant, the city noticeably left out of major economic upswings seen across much of the rest of the Front Range at the time. Gradisar knew the process required to change the city's charter would be a difficult one if he decided to push to get a measure on the ballot by gathering enough voter signatures. However, such measures may also be approved for the ballot by the city council, which is how the question wound up being decided in that year’s November election.

Gradisar argued putting the mayoral system in place would put a stop to a sluggish and inefficient “government by committee” that had held the community back. Instead of a bureaucratic city manager merely administering the conflicting aims of council members, he said the mayoral system would allow for bold and decisive leadership to move Pueblo forward.

Ballot Question No. 2A passed, narrowly, and not long after, Gradisar announced he indeed wanted to be that bold and decisive leader. A little more than a year later, about a third of Pueblo’s registered voters turned out for a January run-off election and put him in charge.

The opposition

On one of the first truly spring-like days of the season, Judalon Smyth strolled the downtown Pueblo Riverwalk near the Arkansas River and called it one of so many special things about the city.

“I could have retired anywhere in the world. I have lived all over the world,” Smyth said. “When my sister and her husband retired here … I came to visit and just fell in love.”

That was five years ago. She became quickly engaged in the community through volunteering at local institutions like the Rosemount Museum.

She said she has not been impressed with Gradisar’s performance in the job of mayor, but that her concern centers more on the system which had put him in power. Pueblo remains only the third city in Colorado with a strong mayor, and it’s by far the smallest.

Opponents of the current system say a city the size of Pueblo may not have robust enough civic or institutional oversight of a strong mayor, that investing such executive power in a single political figure invites corruption.

“I don't care who you name that could be occupying the office and I'm still against the system,” Smyth said. “[A council/manager form of government] diffuses the power of special interests and eliminates partisan politics from municipal hiring, firing and contracting decisions and that’s, I think, important to everybody.”

Last summer, Smyth joined together with City Council member Lori Winner and other opponents of the strong mayor system to explore their own ballot measure petition: a proposal to revert the city back to the council/manager form of government it had before 2019, with one caveat: the council would also now hire the city clerk.

Petitions and acknowledged mistakes

From the movement’s beginnings in the Summer of 2022 until they handed in their final signature total in March 2023, Smyth said the leaders of the petition effort were consistently given the same parameters from the Pueblo City Clerk’s office on how they could qualify their question for the ballot.

Multiple times, through in-person meetings and written communication, petitioners were told by city officials, including City Clerk Marissa Stoller and City Attorney Dan Kogovsek that they would need to gather 3,768 signatures to qualify the requisite amendment to the city’s charter for placement on a special election ballot; a number equal to 10 percent of ballots cast in the previous election. These rules were also posted to the city’s website at the time.

“It was every single day,” Smyth said of her efforts to gather signatures for the petition. “Snow days, cold days, hot day(s). It didn't matter what the weather was. It was every single day out there.”

In their first submission, the petitioners had hundreds of signatures thrown out as invalid, often signatures coming from people who did not live within Pueblo city limits. However, with two additional weeks the group had to verify signatures and collect more, they were confident they had reached the threshold.

By the end of March, however, the city told the group their signature effort was insufficient on two counts. First, more than a thousand of the signatures submitted were again tossed out. This time, the city said the last, notarized pages of several thick packets of signatures had become “disassembled” from the packets, rendering all the signatures of those packets invalid.

Secondly, and most shockingly for the petitioners, they were told the 3,768 signature goal was actually the incorrect benchmark. As relayed in a city press release on the matter:

“Mayor of Pueblo Nick Gradisar discovered the City of Pueblo had incorrectly followed past precedent of an initiated petition in Article 18 of the City Charter for amending a city ordinance rather than following the standards of state law for amending the City Charter.”

In other words, Mayor Gradisar said the group had been given the wrong rules and that the Colorado State Constitution actually requires 10 percent of total registered voters in a municipality to reach the high bar of putting a charter amendment on the ballot.

Instead of 3,768 signatures, the petitioners would have needed to hand in nearly double that: 7,260 signatures.

The city said it regretted the error, but that the petitioners had been told by city officials to get their own independent legal advice on how many signatures they’d need to qualify for the ballot. Regardless, City Attorney Dan Kogovsek stepped down in April as a result of the false information.

Ethical concerns

On the disassembled packets, petitioners have said they had former Pueblo city clerk Gina Dutcher examine their packets and notarize them herself. They say the packets were intact when handed in and if they came apart, it was in the city’s care, in the office of a city clerk who serves at the pleasure of the very strong mayor whose job the effort wants to eliminate.

“None of this passes a smell test at all,” said city council member and petition effort supporter Lori Winner.

Following a similar rationale on the second count, Smyth personally criticized the Mayor, a longtime lawyer himself, for his part in arguing for the higher number of signatures only after the final deadline of their effort.

“Nick [Gradisar] was in my shoes for several years, he was petitioning and lobbying for this strong mayor system for over a decade. Don't you think he actually did know the exact number of signatures required from day one,” Smyth said.

Gradisar denied any impropriety in the manner. He said he, like the city clerk’s office, had relied upon Kogovsek’s guidance and had started looking over charter rules in the state constitution only after the petitioners had declared victory in turning in their packets.

“I’m busy running the city. I don’t have time to pay attention to some of these distractions,” Gradisar said. “We didn’t try to conceal that and conceal the mistake. We disclosed that a mistake was made, even though it was embarrassing to the city.”

Lawyering up

On Monday, the Pueblo City Council voted to retain the services of a private attorney to defend the city against any legal action resulting from the petition effort. The two votes against the contract came from Winner and council member Regina Maestri, another supporter of the effort to move back to a city manager form of government.

“Are we really going to try to wash our hands of this?” Maestri said during Monday’s meeting, criticizing two-year City Clerk Marisa Stoller. “I don’t know if it’s lack of experience that brought this all upon us, but it’s just been really unfair to the community.”

Council President Heather Graham, in her vote to fund the attorney, said she wanted to make sure the city was properly covered if a lawsuit heads its way. Monday’s council meeting was a heated public discussion, as any action against the city was likely coming from council member Winner, who told CPR News she had already personally put $4,000 into legal fees for such a suit, resulting in a letter of intent.

“Before we start going after our own city clerk and saying she’s inexperienced, you [petition supporters] had a very experienced clerk helping you with your process and you still didn’t get it right,” Graham said, reiterating the petition process explained to supporters by Stoller was at the direction of City Attorney, Dan Kogovsek.

To complicate things even more, Graham, along with council member Dennis Flores, are also running to unseat Gradisar as Pueblo’s next strong mayor this fall.

The law is the law

During an interview last week in city hall, Stoller expressed frustration with the outcome of the petition process, but said there wasn’t anything she could have done differently. She said the incorrect parameters regarding the charter amendment process had been posted on the city’s website and election calendars for years. She called it bad luck that the error was discovered in the course of such a passionate and divisive local effort.

“The fact that it happened to them is very unfortunate, but it wasn’t aimed at them,” Stoller said. “I would have liked them to have been able to attempt to go for the 7,000 signatures .… I don’t know if they would’ve made it in that time period either, but they deserved the right to try.”

As for the disassembled petitions, Stoller described that as a policy around which she does not have authority to ignore. She also flatly rejected the assertion from the petitioners that Gradisar influenced her to invalidate the packets.

“We had discussions about some of the issues with the petitions and [Mayor Gradisar] argued his points and I argued my points and the city attorney argued his points,” she said. “Anything that I couldn’t agree with never took place.”

Council member Winner said Tuesday the council's decisions to reject putting the city manager question before voters and to retain an attorney has led the group to put a hold on any legal action against the city.

She said the money they could raise for the courtroom couldn’t compete against the city using taxpayer dollars to defend its system of government.

“It’s over,” she said.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated when petitioners were required to hand in the 7,260 votes to qualify their question for the ballot.