By Jennifer Brown, The Colorado Sun, and Melanie Asmar, Chalkbeat Colorado

Colorado is doubling the funding next year for schools that enroll students whose mental health or medical needs are too intense for regular schools to handle, calling for 12 new schools to open within the next three years.

The number of these specialized schools, which operate as day centers or are part of residential treatment facilities or hospitals, has fallen over the past two decades to 30 from 80. They offer a combination of therapy and academics in an effort to stabilize thousands of students a year so they can return to their home schools.

But even as the state attempts to shore up a system that's been sapped by staff shortages, inadequate state funding and other challenges, it is nearly impossible for parents and other members of the public to get answers to a fundamental question: Are students enrolled in the schools safe and learning?

Facility schools are intended to act as temporary programs of last resort to stabilize students so they can successfully return to their home schools. Yet, the state does not keep track of how many students return to regular school or how many eventually graduate.

The state requires facility school students to take its standardized tests, but does not provide individual school results, citing student privacy because the classes are so small.

The schools exist at the intersection of the educational, mental health and juvenile justice systems. Multiple state agencies are responsible for monitoring the schools, but those visits in some cases happen only every two years and reports from the state education and human services departments aren’t readily available to the public. The Colorado Sun and Chalkbeat Colorado filed multiple requests under public records laws to receive reports, some of which were redacted, that offer a glimpse into the facility school environment.

Maintaining separate schools for children who act out aggressively, frequently run from school, or have severe medical or intellectual needs is controversial, with some parents and disability rights advocates questioning whether they are holding centers for kids with behavior problems. It’s clear Colorado needs more facility schools to accommodate the growing number of children with behavioral health struggles, but advocates also want enough information to ensure kids are safe and learning.

'We don’t really have a choice but to make them better'

The prime sponsor of the new law that will pour an additional $18 million into facility schools next year, increasing their funding by 2.6 times what’s in current law, agrees that Colorado needs more data about whether facility schools are working. Sen. Rachel Zenzinger, an Arvada Democrat and chair of the Joint Budget Committee, hopes her legislation will force the various state agencies that oversee the schools to cooperate and report better data on outcomes within a few years. It also requires that schools earn accreditation in order to receive state funding through the new law.

“There are some facilities where we do question whether they are simply warehousing kids and whether they offer good programming,” said Pamela Bisceglia, executive director of Advocacy Denver, which speaks up for Denver Public Schools children with special needs. She has visited several facility schools over the years with parents who are deciding where to place their children. Some are clean, calm and excelling at teaching children, she said. And some are not.

Bisceglia recalled visiting one Denver school where children ages 5-17 were all in the same room, some lying on the floor, no one interacting with each other, while several staff members in the room were scrolling on their phones.

| “Last Resort” is a Colorado News Collaborative-led four-part investigation by Chalkbeat Colorado, The Colorado Sun and KFF Health News into the collapsing system of schools that serve some of Colorado’s most vulnerable students. The state is now scrambling to shore up what are known as facility schools, which enroll thousands of students a year with intense mental and behavioral health needs. Part 1: The schools that take Colorado’s ‘most vulnerable’ students are disappearing. Part 2: Students in rural Colorado are left without options as specialized schools close. Part 3: Colorado is now pouring more money into facility schools, but are they helping? Part 4: How Colorado is filling gaps as last-resort schools dwindle |

“They were simply trying to keep them from hurting themselves or others,” she said. “There wasn’t any learning going on. There wasn’t any individualized therapy.”

The Arc Pikes Peak Region believes all children should attend their neighborhood schools rather than facility schools where they end up cut off from their peers, said Connie McKenzie, an advocate for children with disabilities. If children do end up in a facility school, their time there should be temporary, with the goal that they will gain skills so they can return to their neighborhood school.

“In actuality, I don’t think that happens as often as anyone would like,” McKenzie said. “In my experience, a lot of times when kids are sent to facility schools, they never return to their neighborhood schools. Sometimes it’s a moving target for them to try to meet to get back into that neighborhood school. Sometimes they just never learn the skills that the school feels that they need.”

Maureen Welch, a member of a task force that studied facility schools for the past year and whose son attended one, said Colorado needs “a lot of light and sunshine” to illuminate the process of approving facility schools in the next few years. She wants to make sure the state is bringing in quality programs ranging from small, neighborhood startups that serve a handful of students with related issues, to large, national operations.

“We need to actually have them learn and move forward,” Welch said. “Yes it’s expensive, but we don’t really have a choice but to make them better. What are we going to do? Put these kids in the correctional system? There is no place to put them because there are not institutions anymore. We will always have a population of kids that can’t be served in a public school district situation.”

Under the new law, schools must receive accreditation based on recommendations from the state facility school board, a panel created in 2008. Board chairperson Steven Ramirez did not return multiple requests for comment from The Colorado Sun and its partners.

The Office of Facility Schools, within the Colorado Department of Education, pushed back on the characterization that facility schools are just a place to keep kids that school districts don’t want to deal with anymore.

“Are there facilities somewhere out there that exist that maybe aren’t being as effective as they need to be or warehousing kids? I don’t think we can eliminate that as a possibility,” said Paul Foster, the executive director of exceptional student services for the education department. “I think we can pretty safely say if they’re in our facility school system, that that’s not the case.”

If it were the case, he said, monitoring visits by the department would have turned up “serious or even egregious” violations instead of the more pedestrian problems that they more commonly find.

Facility schools are not rated based on their test scores in the same way that traditional public schools are, Foster said. While students at facility schools are required to take state standardized tests, state officials take into account that students have “unique and pretty significant needs — and that’s why they’re in a facility school setting,” Foster said.

Callan Ware, the executive director of student services for Englewood Schools, a small district south of Denver, said that when she sends a student to a facility school, it’s because their behavior is so dysregulated — they’re skipping class, getting kicked out, or harming themselves — that they struggle to concentrate and learn.

“While we do absolutely have academic expectations of facility schools, the No. 1 goal is, let’s learn the skills you need to be successful in a public setting,” Ware said.

She recalled one student who struggled with boundaries and impulsiveness and who routinely got sent home from public school for touching other students in class. After less than a year of daily therapy in a facility school, the student “totally turned it around,” she said. His engagement in academic tasks skyrocketed and when he returned to public school, “we could see the kind of student he could be because he wasn’t getting kicked out of class all the time.”

Human services reports reveal safety issues involving cleaning chemicals, restraints

The job of ensuring students are safe and getting a quality education in facility schools falls to multiple state agencies.

The Colorado Department of Education is charged with making sure the schools are following curriculum guidelines and the components of students’ individualized special education plans. The state Department of Human Services, which includes the child protection division, monitors schools to make sure students are safe. Human Services licenses schools in day-treatment or residential centers, while the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment licenses those in hospitals.

When Colorado lawmakers implemented the Office of Facility Schools at the state education department in 2008, they ordered the office to create curriculum standards, graduation guidelines and an accountability system for the schools. While those standards were written, some of the performance data isn’t tracked or is not easily accessible to the public.

In response to a records request, the Colorado Department of Education provided average standardized test scores across all facility schools — they are lower than the state average, which state officials attributed to their intense behavioral health needs. Colorado’s strict student privacy law requires redacting data about small student groups, and the state wouldn’t provide any test data for individual schools.

The Colorado Sun and its partners gleaned what data we could by seeking documents under state open records laws. The state doesn’t track graduation rates or keep a count of how many students return to their home districts after attending a facility school. The Department of Human Services charged $90 for redacted reports on child safety. One police department said it would cost $4,700 for copies of reports that could shed light on why police were called so frequently to a facility school and the residential center where it’s housed in Colorado Springs.

The state human services department conducts regular inspections of schools in day-treatment and residential centers, focusing on whether children’s rights are protected. When the division receives a complaint about the way a child was restrained or injured, a state monitor investigates to determine if the school violated state regulations regarding child abuse or neglect. The Colorado Sun reviewed a year’s worth of school monitoring documents after receiving redacted reports through state open records laws.

The reports shed light on the often chaotic, and at times unsafe, environment at schools for students with a history of behavior problems deemed too much for regular schools to manage.

Mount Saint Vincent, a Denver day treatment center with a school, was cited last summer after a child was able to get ahold of cleaning chemicals and spray them at staff, sending a worker to the emergency room with possible eye and inhalation injuries.

The school was cited again in September after a father of one of the students complained about a red mark on his child that he said was from being held down by staff members on a “hot sidewalk.” A state report says the child threw a water bottle and began hitting two workers after being told to complete math before playing. The staff members restrained the child in a supine hold, face up on a paved courtyard, as the child screamed “Let my arm go” and “The concrete hurts.”

Tennyson Center, another Denver day treatment center, was cited in January for failing to supervise a child who had a known history of cutting herself. The girl hurt herself in a bathroom after staff failed to check on her, according to one Colorado Department of Human Services report.

Devereux Cleo Wallace, which has a day treatment school in Westminster that is closing at the end of this school year, was investigated after a worker chased after and collided with a child running toward a maintenance shed containing tools.

12 schools cited by education department in past five years

In the past five years, the Colorado Department of Education has ordered 12 facility schools to take corrective action for violations ranging from not uploading individualized special education plan documents, using curriculum not aligned to state standards, and cutting into academic time by pulling students out of class for therapy, according to monitoring and corrective action reports reviewed by Chalkbeat Colorado

Five of those 12 schools are closed now. That means seven of the 30 facility schools currently operating — or about 23% — have had violations in the past five years. Most were addressed by the next time state monitors visited.

Poplar Way Academy, inside a behavioral health hospital in Littleton, was cited for cluttered and dirty learning areas, “minimal structure,” and lots of downtime for the 17 students who were there when the monitors visited last June.

“Students had control over the radio and music was playing loudly as they worked,” said the report, which was by far the most egregious of 88 monitoring reports reviewed for this story. “There were no redirections for inappropriate language or behaviors, and students were often left unsupervised or allowed to walk out of the classroom with no redirection. Inappropriate boundaries were noted among students,” who were male and female.

The school is different from most in that it’s for teenagers who have been admitted to a hospital on mental health holds, meaning they were deemed a danger to themselves or others. The average length of stay is just four to five days, the report says.

The school’s director of special education, Deon Roberts, said that since state officials’ last visit, the school has hired more teachers, increased staff training and expanded the curriculum. The school is “committed to continuous improvement while providing much-needed educational services to a challenging population of students,” she said in an email.

The majority of the violations, however, are for “quick fixes” that schools can address with more training or resources, said Judy Stirman, director of facility schools at the state education department.

State education officials try to help schools with a background in mental health treatment understand their educational obligations, said Foster, with the state education department. “If I’m a therapist or someone at a facility school, I’m looking at the whole package, and so I may not understand that the school side of it has committed to a certain plan for this child in addition to the treatment plan you’re doing.

“Special education is pretty technical, so you can have technical violations,” he said. “Don’t hear me say that technical violations don’t need to be treated seriously. But a technical violation that is quickly remedied is not usually harmful to the student.”

Facility schools with violations get a visit each year from a pair of state monitors. Schools without violations get a visit every other year from monitors who use a 98-item checklist. In addition to whether schools are complying with the mounds of federal requirements related to special education, the monitors determine whether teachers are properly licensed and staff are using positive behavior interventions with students and not punitive ones, for example.

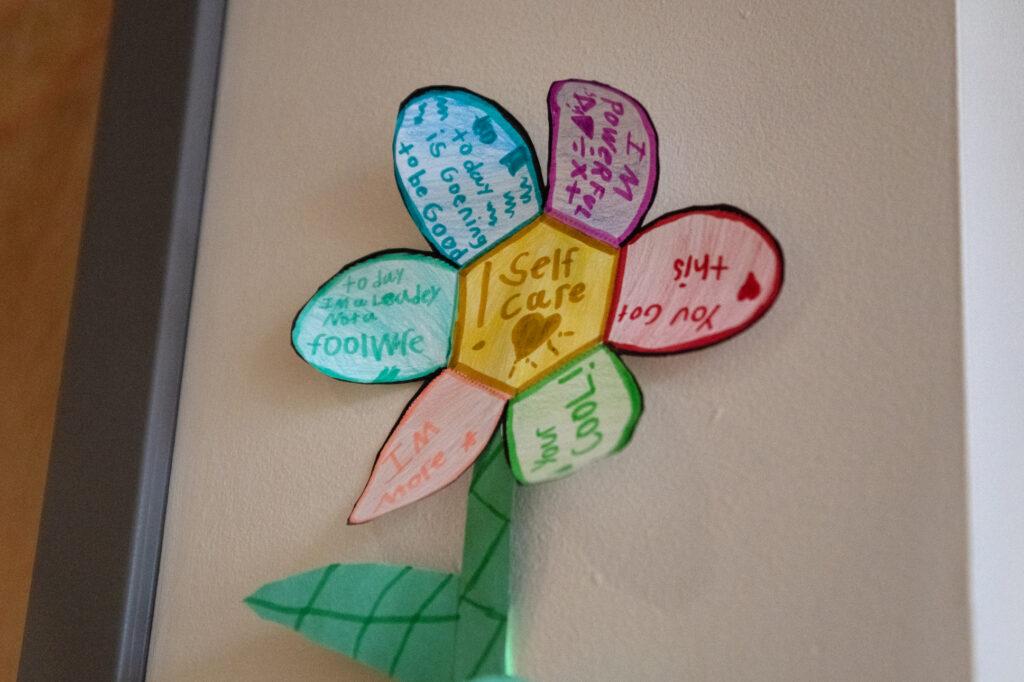

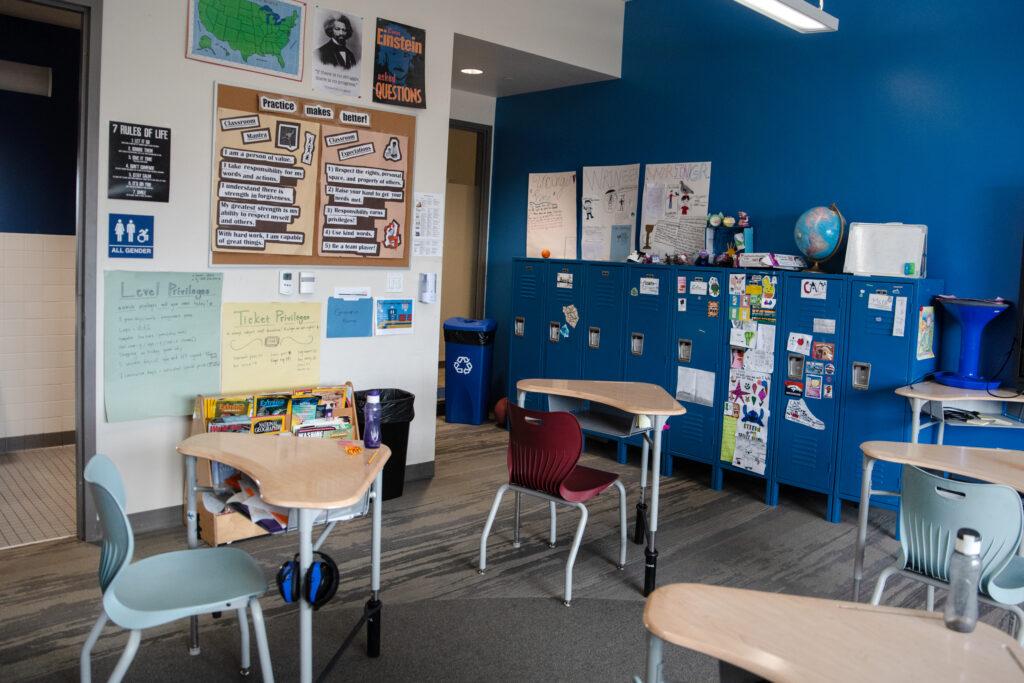

The reports provide a window into what the schools look and feel like. Many describe bright classrooms with student artwork on display. They note that most schools use a reward system where students with good behavior earn tickets that they can redeem for prizes. Some schools hold events like talent shows and carnivals. One has a basketball team. Another has a student choir. A few have therapy dogs, gardens, or culinary arts programs.

Juvenile records laws shield information about safety

Several of Colorado’s facility schools include a mix of students who live at home with their parents and students who are in foster care and live in the residential treatment center that contains the school.

This clouds transparency about the safety of the schools, since police regularly visit residential centers for young people who might have lived in multiple foster homes and juvenile justice centers.

Public records requests from The Sun to police departments in Colorado Springs and Denver revealed a constant drumbeat of emergency calls to facility schools or programs housed in the same complexes.

Between April 2021 and the end of March, for example, Colorado Springs police responded hundreds of times to the J. Wilkins Opportunity School, 10 Farragut Ave., and the residential program across the street, 17 Farragut Ave., police records show.

More than 100 emergencies were reported at the school, including 18 assaults as well as sexual assaults, threats, harassment, 911 hangups and suicide attempts. The residential facility, where some of the students live, accounted for more than 470 police calls during that period, with dozens more reports of assaults, threats, indecent exposure, missing children and sexual offenses, the records show.

No details were provided beyond the time, date and nature of each call. Police said a request for more records of those calls would require an estimated $4,700 payment for research and redaction fees.

Managing outbursts and aggressive behavior is nothing new at the J. Wilkins Opportunity School, said Lauren Campbell, the chief operating officer of the Griffith Centers, which runs the school and residential program.

“Some of that behavior is why these kids — a good portion of them — are here,” Campbell said. “It’s not an ideal piece of learning, clearly, but unfortunately it’s the safest place for most of these students to be in general.”

When police are called, the children involved in the emergency are separated from other students, so officers aren’t entering classrooms, Campbell said. That minimizes disruptions and allows staff to restore order and return to teaching, she said.

A threat that might get a child suspended or even kicked out of another school often results in a safety plan involving special accommodations, such as a temporary transfer to a different classroom.

Campbell said calls to police had increased in the past two years, citing a staffing shortage that made it harder for workers to defuse conflicts on their own.

The campus used to operate five residential centers, housing up to 40 children. But they closed all but one after the passage of the federal Family First Prevention Services Act, which pushed states to send fewer children to residential care.

The closures reduced the campus staff by roughly 50%, and the only remaining residential center was reserved for the kids with the severest needs, leading to more frequent calls for help, Campbell said.

Still, the emphasis remains on keeping children safe, and on campus.

“They end up in less troublesome situations than in a school setting,” she said. “We’re less likely to press charges than a school would. If they’re here, we’re not suspending them, either.”

In Denver, police similarly logged thousands of calls per year to facility schools or the complexes housing them, also for reports of assaults, missing children and various disturbances, records show. But Denver police declined to provide incident or arrest reports that would disclose more detail, citing a state law meant to protect juveniles’ privacy.

McKenzie, with The Arc Pikes Peak Region, worries Colorado isn’t doing enough to make sure kids at facility schools are safe.

“There isn’t that oversight,” said McKenzie, who advocates for a handful of families each year whose kids end up attending facility schools, noting some students are terrified of returning to one.

“They were afraid,” she said. “They were legitimately afraid of what was going to happen to them if they went back to a place where they felt they had been abused.”

Becky Miller Updike, director of the Colorado Association of Family and Children’s Agencies, which represents some of the largest youth treatment facilities in Colorado, is hopeful that this year’s legislation will set facility schools on a trajectory of better funding and more accountability.

“With this new investment from the legislature, facility schools will now track data and access technical assistance more robustly than ever before,” she said. “We will have new ways to measure what’s working and what’s not.”

Zenzinger’s legislation requires multiple state agencies to work together to help current schools function better and new ones open.

“Facility schools don’t neatly live under one department. That’s why they are such a challenge,” she said. “We are definitely mandating a new level of cooperation between these different departments so that they are each doing their part.”

As part of the new accreditation requirements, schools will have to report additional data showing student outcomes, and the new law provides funding for data collection because “we absolutely would like to track things a little bit better,” Zenzinger said. A task force that has studied facility schools for the last year and made recommendations ahead of Zenzinger’s legislation will continue to meet and help determine what data the schools are required to report.

“We want them to be accredited and deliver good quality public education,” she said. “Obviously they aren’t traditional schools. You are not going to have passing periods and a full schedule every day. But we want to make sure that children in facility schools are able to graduate and go on to college and have productive lives.”

One child out of 11 returned to a regular school

On a recent day at Skyline Academy in Denver, elementary school children read quietly at their desks as a flat-screen television at the front of their classroom played soothing music and showed a trickling waterfall.

The desks at Skyline, which is run by Denver’s community mental health center WellPower, have bungee rubber bands that stretch from one chair leg to the other so kids can put their feet on them and bounce as they study fractions or read aloud. Each child gets a plastic rainbow wiggle slug they silently twist and curl in their palm, helping them relieve anxiety. Children can use standing desks or “wobbly” stools inside of regular chairs. There is a “chill room” and a “peace room” containing bean bags and swings where students can hang out if the classroom gets too stressful.

The classrooms, decorated with cheerful colors and maps, are on one side of the building of the Dahlia Campus for Health and Well-Being. On the other side are the mental health center’s counseling offices where children get individual and family therapy.

The school has a capacity for 24, yet only 14 desks are full — even as school districts across Colorado are scrambling to find spaces for children whose needs are beyond what they can handle.

Program manager Erica Edewaard said that’s because many of the children who’ve been referred to Skyline in recent months have behavioral issues more intense than even Skyline can accommodate. Some of the kids referred by school districts, she said, need residential treatment.

Skyline, not far from busy Martin Luther King and Colorado boulevards, won’t accept children who repeatedly run away because they could get hit by cars. Under state law, schools like Skyline are not allowed to lock their doors and staff are prohibited from physically restraining students unless there is imminent risk of danger to themselves or others. Skyline also won’t typically take kids with a history of destroying property or assaulting teachers or other students, especially if they are nearly the same size as Edewaard’s staff.

“I also have to take into consideration the size of the student relative to the size of my staff,” Edewaard said. “If I'm always relying on just my two tallest staff members, that's going to burn them out really quickly.”

The goal at Skyline is that students learn to cope with their anxiety, depression or attention disorder so they are able to function and learn in a regular classroom. For most, however, a direct transition to regular school is not that easy.

Eleven students have left Skyline in the past year, according to data provided by the school. Three students left for hospitalization or a residential treatment program, one “aged out” and a handful of others went to other step-down or specialized school programs.

Only one returned to a regular classroom.