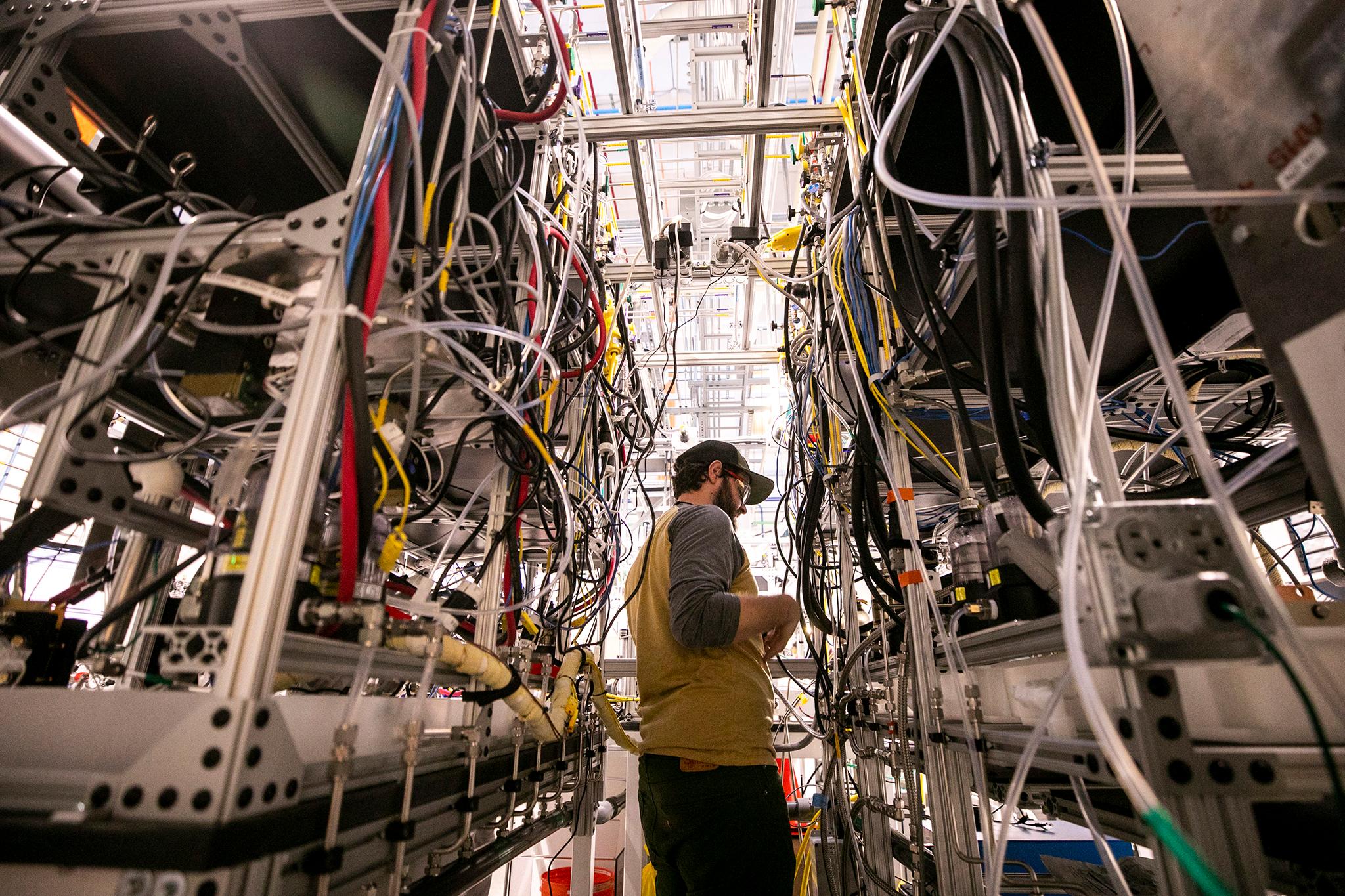

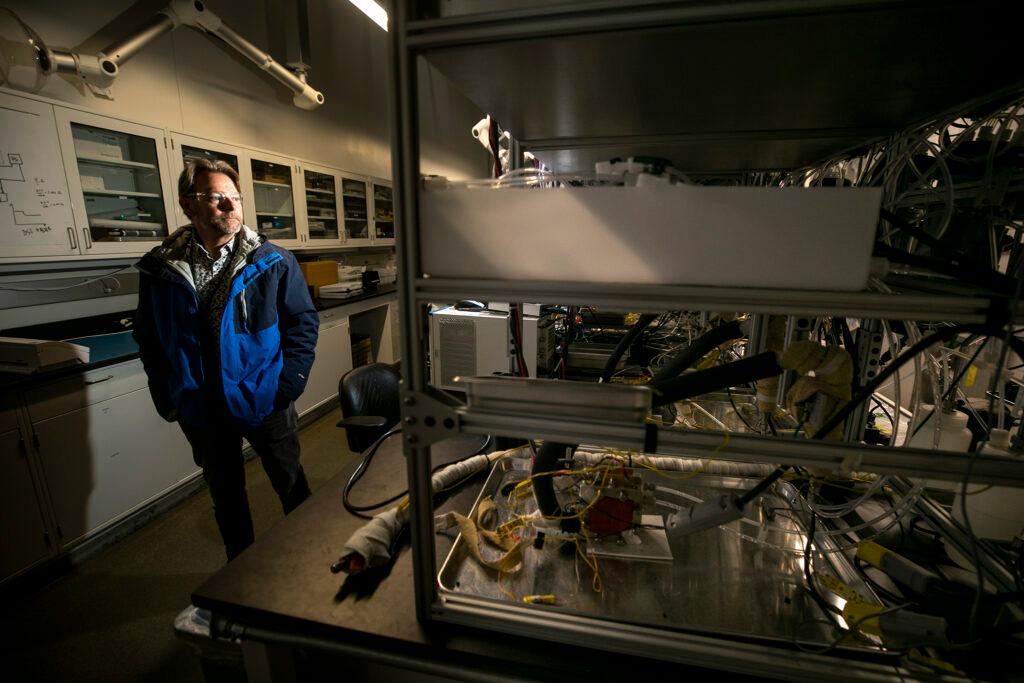

Inside a lab at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, a team of scientists bustles around a tall stack of metal plates known as an electrolyzer.

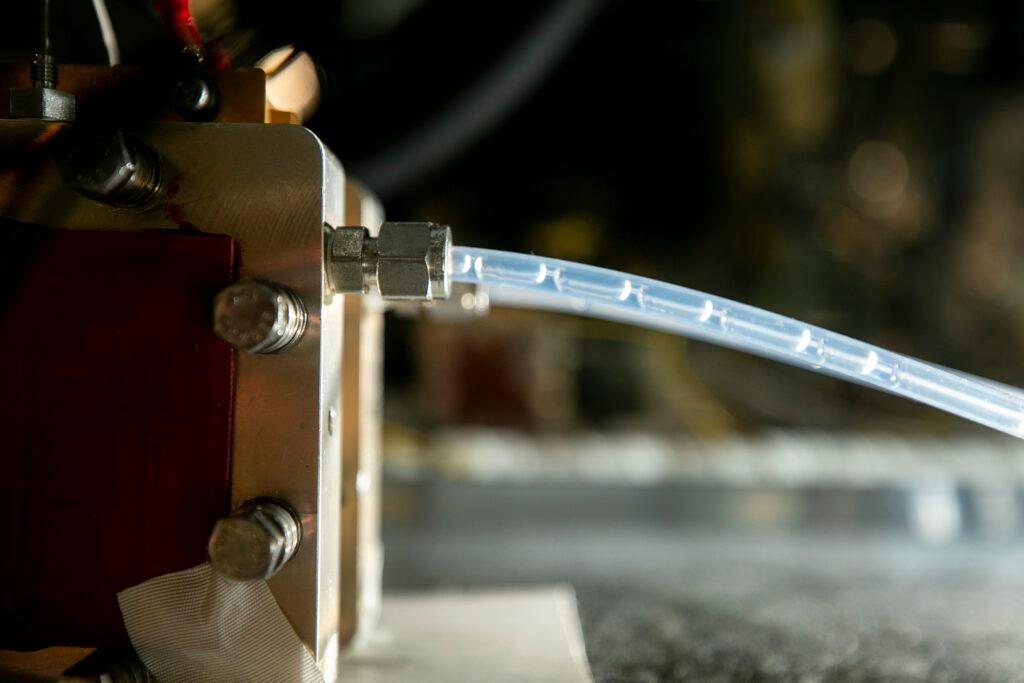

A blinking blue light proves the machine is working on a task the U.S. government sees as a critical part of its strategy to confront climate change. The system uses electricity to split hydrogen out of purified water, producing a clean-burning fuel with an energy density greater than gasoline or diesel.

"The unique thing about hydrogen is it's a molecule," said Keith Wipke, who leads the laboratory's fuel cell and hydrogen technology program. "You can move it around physically. You can store it. It just stays there."

This characteristic is why hydrogen tanks are far lighter and faster to refill than hefty batteries, Wipke says. And using the flammable gas doesn't emit any carbon. Together, those benefits could make hydrogen an ideal replacement for fossil fuels in long-haul trucks, ships and aircraft, not to mention industrial processes to make steel or fertilizer.

But a chorus of environmental groups now sees a hidden risk with so-called "green" hydrogen. Without sufficient guardrails, they warn a future fleet of electrolyzers in the United States could draw power from gas and coal power plants, resulting in a rise in climate-warming emissions, not a reduction.

Due to those concerns, Colorado lawmakers recently amended a bill to include the nation's first-ever clean hydrogen standards. Gov. Jared Polis is expected to sign the legislation, offering a potential preview of similar restrictions under consideration at the national level.

A battle over the fuel of the future

Rachel Fakhry, a climate advocate focused on emerging technology at the Natural Resources Defense Council, said the policy could provide a blueprint for the U.S. Treasury Department, which is currently considering guidelines for a generous tax credit outlined in President Biden's Inflation Reduction Act. The group estimates it could be worth more than $100 billion over the lifetime of the incentive.

"We have a few more months to make sure the rules are quite rigorous," Fakhry said. "I really hope Colorado's efforts are reflected in those guidelines."

Meanwhile, early investors in clean hydrogen — which includes automakers, oil and gas companies and some renewable energy producers — have pushed for more flexibility around their future energy sources. In Colorado and at the federal level, they warn too many restrictions could suffocate the young industry before it takes off.

Those same arguments defined a recent debate at the Colorado state capitol. In the 2023 legislative session, Democratic lawmakers proposed a bill to set up an approval process and a state-level clean hydrogen tax credit.

Part of the goal was to sweeten a multistate bid to build a "hydrogen hub" in the Rocky Mountain West. Together with Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico, the Polis administration is currently leading an effort to draw from $8 billion in federal funding for four or more regional hubs across the country. The applications ask for $600 million for Colorado alone.

Supporters say the federal dollars could bring jobs and private investment, but environmental groups have been worried it could move the state further away from its ambitious climate goals. The recent legislative proposal brought those concerns out into the open.

To ensure emissions reductions, climate advocates proposed restrictions built around three principles: Requiring companies to build new clean energy sources to power their hydrogen plants, locating those energy sources close to production facilities and mandating that companies only produce hydrogen at moments when wind and solar are readily available.

A climate-modeling group at Princeton University initially proposed the ideas adopted by climate advocates in Colorado. In a recent study, the researchers found those restrictions could allow green hydrogen to expand with minimal carbon pollution.

But Frank Wolak, the president and CEO of the Fuel Cell and Hydrogen Energy Association, said the rules are unfair to his emerging industry. He doesn't see why hydrogen plants should be treated differently than other zero-emissions technologies that plug into a less-than-perfect grid, like electric cars or heat pumps.

"The larger issue is how do we get community adoption of more and more renewable resources as fast as possible so that electrons can flow to multiple uses, including hydrogen," Wolak said.

Colorado's new standards are a compromise

Will Toor, the director of the Colorado Energy Office, shares some of those concerns. That's partially why the final version of Colorado's proposed clean hydrogen standards only enforces the toughest restrictions when one of two milestones are met: After 2028 or when Colorado’s hydrogen industry builds 200 megawatts of electrolyzers. It also only applies to investor-owned utilities making hydrogen or companies seeking the state-level tax credit.

Toor said the tiered approach to regulations makes sense in Colorado, which has plentiful access to wind and solar power. He said the state supports a similar, gradual approach at the national level.

"We do think it's important to have some flexibility in the early days of deployment to allow the industry to grow," Toor said.