For most Coloradans, springtime has brought much-needed relief from high energy bills.

That’s after households watched their gas and power costs spike over the winter due to frigid temperatures and high natural gas prices. In some cases, monthly bills doubled or tripled compared to a year earlier. Warmer weather and lower fuel prices are now bringing bills back down to earth.

But the crisis isn’t over for Colorado residents like Krissiel Abeyta.

The single mother of three from Lakewood has always struggled to pay off her outstanding debt to Xcel Energy, the state’s largest gas and electricity company. She stayed afloat thanks to bill assistance programs and a near obsession with energy efficiency.

Abeyta offset the costs of running power-hungry oxygen and CPAP machine that assist her breathing at night by unplugging the dishwasher and relying on LED nightlights. The strategies worked well enough — until her monthly bill started to climb in the fall of 2022 from around $300 to a peak of around $450 in January. Unable to pay, she now owes Xcel Energy about $1,400.

“What am I gonna do in the winter?” she said. “When I can’t catch up, are they going to shut my electricity off and make us freeze?”

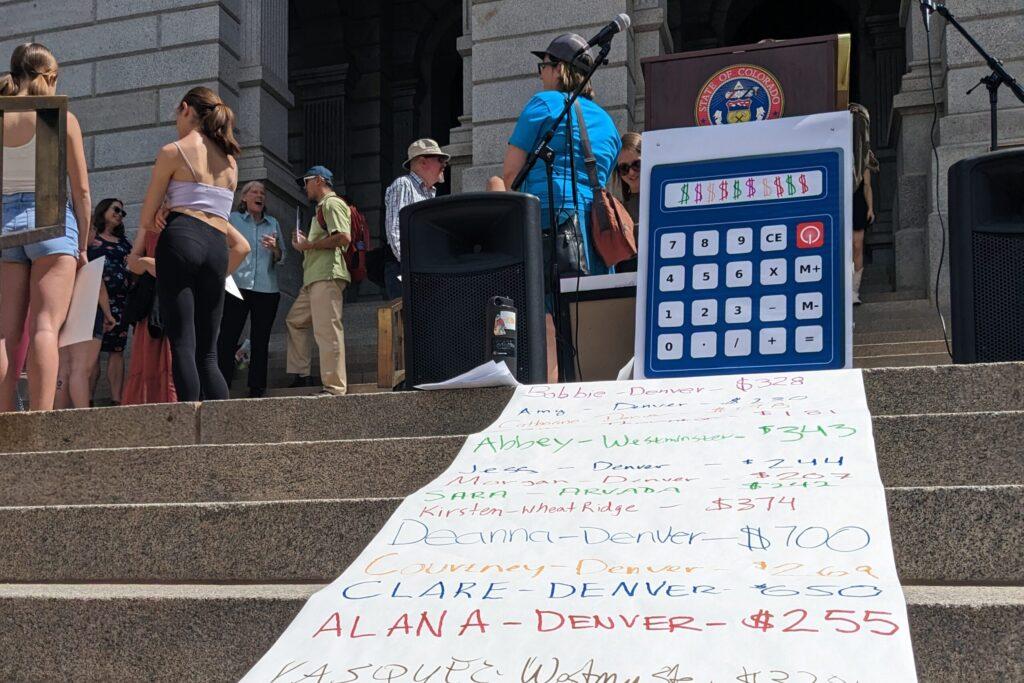

Recent data submitted to state utility regulators show Abeyta is far from alone. For the last few years, the number of Colorado households owing money to Xcel Energy has hovered around 250,000. Meanwhile, the average debt across those households almost doubled, from about $225 in January 2019 to about $550 in March. The most severe rise occurred over the last six months.

Bill assistance programs have also seen a steep rise in applicants. Over the last winter, more than 130,000 Coloradans applied for the state’s Low-Income Energy Assistance Program, a 16 percent increase over the previous winter.

Requests for help haven’t disappeared with the warmer weather, either. Energy Outreach Colorado offers assistance outside the winter heating season. In April and May, it continued to receive around 6,000 calls a week to its energy assistance helpline, about 30 percent more than it expects in a typical spring.

It’s unclear if recent legislation will offer any help to low-income customers

After months of ratepayer outrage over surging energy bills and Xcel Energy reporting record profits that topped $1.7 billion in 2022, lawmakers responded.

Democrats in the state House formed a special joint committee to investigate the root causes of rising energy costs during the last legislative session. Those hearings led to landmark legislation, signed by Gov. Jared Polis, which includes a broad set of policies its backers say will help reduce customers’ bills over the long term.

The centerpiece requires utilities to propose plans to insulate customers from future swings in natural gas prices. Another provision bans investor-owned utilities from charging customers for lobbying and advertising expenses. And to encourage an ongoing shift away from gas stoves and furnaces, the new legislation ends a ratepayer-funded subsidy for natural gas connections in new homes.

While the plan won broad praise from climate advocates, Jennifer Gremmert, the executive director of Energy Outreach Colorado, was “underwhelmed” by the lack of immediate relief offered for customers. She’s uncertain if the plan will do anything to reduce bills or help those already in debt to Xcel during the coming summer and winter.

Laura Hernandez, a mother of five from Greeley, also hoped the legislative push would result in direct financial assistance for families like hers. After years of struggling to pay utility bills, she said her household now owes around $2,900 to Xcel Energy.

“I'm glad that people will not struggle in the future hopefully with this, but those of us that are struggling now? We're up a creek without a paddle,” Hernandez said.

State Senate President Steve Fenberg, a Boulder Democrat who sponsored the legislation, said the lack of direct financial assistance shouldn’t come as a surprise.

“We sort of tried to say that from the beginning: The purpose here is to stop or slow down and insulate consumers from the cost drivers. And so it was more a policy conversation than direct funding relief,” Fenberg said.

He also thinks the newly required planning around natural gas swings mandated in the legislation could help control costs next winter.

Meanwhile, there are separate efforts to increase funding for bill assistance, but they rely on additional charges to everyone’s utility bill.

One example is a law approved by state lawmakers in 2021. It required Colorado investor-owned utilities — Xcel Energy and Black Hills Energy — to tack a 75-cent fee on customer bills to fund programs offered by assistance organizations like Energy Outreach Colorado.

In May, utility regulators also approved an Xcel Energy proposal to add about $47 million to its gas and electric affordability program, which offers payment plans and discounts for low-income customers. A portion of the money will also help pay down the customer’s existing debt. To fund the expansion, the company will add $1.48 to a fee already charged to its combined gas and electric customers.

At the same time, the company is pushing regulators to approve a $312 million rate increase in Colorado, which would add another $7.33 to the average residential electric bill, according to estimates filed with the utility commission. The company argues the rate increase will help pay for past projects and maintain a healthy profit, which will attract capital to pay for future projects necessary to meet statewide climate goals.

The pattern is a concern for Gremmert, the Energy Outreach Colorado director. An analysis from state utility regulators showed a combination of rising natural gas costs and investments in new energy projects is currently pushing up bills. To blunt the impact, the Colorado Energy Office has suggested households could shift away from natural gas by installing electric stoves or home heat pumps

Gremmert worries that lower-income families can’t afford to pay for those investments. In the end, that could lead to even higher bills — and more demands for direct assistance.

“That just is a natural tension that we're seeing — and we're gonna see this for the next several years, frankly — until some of the promises of the clean energy future start to come true,” Gremmert said.