In a warehouse in Arvada, there’s a place called Crater Beach. It’s really just a giant open box filled with about 30 tons of sand and a handful of artificial boulders. And on one recent day, rolling around Crater Beach, is a rover. To the degree that “breadbox” is a relevant yardstick in a 21st century discussion about space entrepreneurship, this test rover is about the size of a breadbox.

Near the beach, a 20-something is using a modified Xbox controller to operate the rover and help test its autopilot software. Does it do the right thing when it rolls into one of those boulders? How does it adjust to the sand?

The experiments in Crater Beach are some of the innumerable late-stage tests the company Lunar Outpost is running before they try to send a rover, one much larger than a breadbox, to the South Pole of the Moon later this year.

There are about 500 companies focused on the space industry in Colorado and more and more of them are opting for a different path from the military-focused applications that have dominated the state’s contribution for decades. Instead, these relatively small startups are trying to make a mark in what they see as a commercial space sector poised for explosive growth.

And now may be just the time to do it.

Military roots

Of those 500 or so companies, about half of them are based in Colorado Springs, and it’s no wonder why.

The worldwide Global Positioning System (GPS) is run out of Schriever Space Force Base east of the city. The North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) operates from the nearby Peterson and Cheyenne Mountain bases. The U.S. Air Force Academy was an early leader in the field of aerospace education.

Additionally, Colorado’s inland location made it a logical host for some of the country’s first intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Today, the part of the space sector specifically serving the Department of Defense is only expected to grow, especially with Colorado Springs hosting the largest share of personnel in the new United States Space Force.

The Catalyst Campus for Technology and Innovation is a startup incubator on the east side of downtown Colorado Springs. Senior Executive Director Dawn Conley said about 80-percent of the companies on the campus are space-focused; the fact that almost all of those cater to military needs is itself representative of a shift in the overall industry.

“Over the last couple of years or several years, the reliance on the space domain … especially how the military conducts some of their business, has evolved and is very important and progressive,” Conley said.

The military has long sought contracts with the country’s largest aerospace corporations. Think Lockheed Martin. Think Raytheon. Think Northrop Grumman and Boeing. That certainly hasn’t changed. However, the rapidly accelerating competition with potential adversaries like China and Russia has even some of the smallest startups successfully pitching their new ideas and technologies.

“Even the Department of Defense has recognized that that’s where the real innovations and solutions are coming from and that’s where the opportunity is,” said Andy Merritt, chief strategy officer for The O’Neil Group, a real estate and venture capital firm that owns Catalyst Campus and invests in emerging space and cybersecurity companies.

Small and scrappy

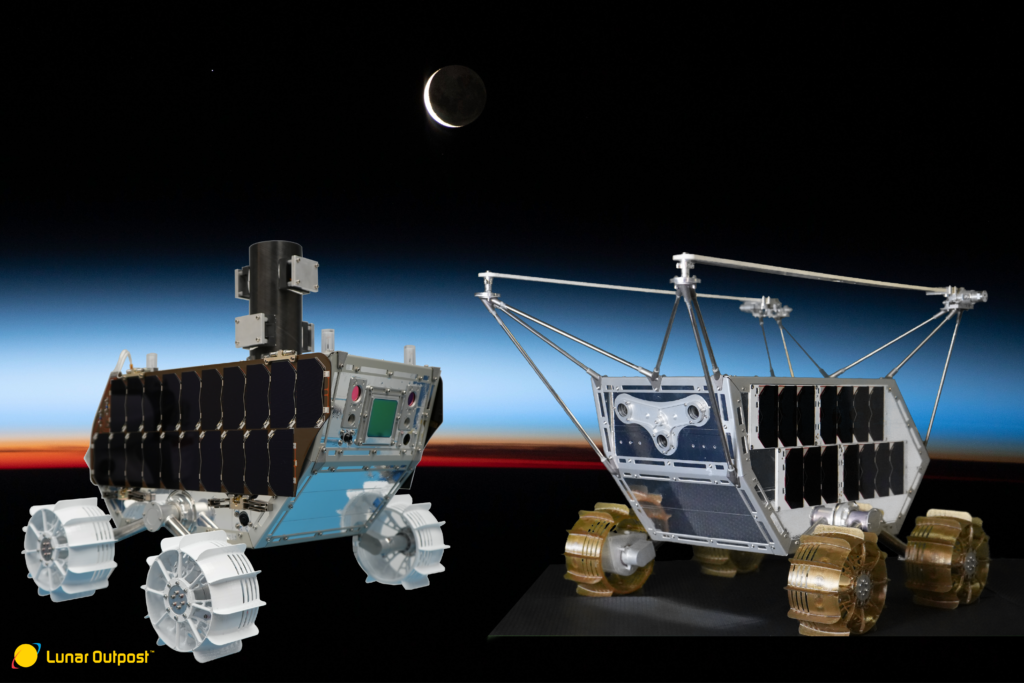

The rover that Lunar Outpost is planning to send to the Moon on a SpaceX rocket in November is not much to look at. This vehicle is closer to the size of a wheelbarrow than it is to a breadbox and — to the untrained eye — the clunky silver box does not look too dissimilar from what high school and college students compete with each year at the Colorado Robotics Challenge at Great Sand Dunes National Park. But, of course, in reality, the Lunar Outpost rover is the product of thousands of hours of planning and tens of millions of dollars.

It is engineered to handle the Sun’s circuit-frying direct radiation and to tolerate temperature changes from -200 to 200 degrees Celsius (changes which happen in seconds in the vacuum of space.) It needs to be able to transmit its exact location from a world without GPS and make sure the technologies other private companies have paid Lunar Outpost to attach to the rover have a chance to do their jobs as well.

It also needs to know when it has run into a boulder and adjust — on its own — accordingly.

When Justin Cyrus, 30, co-founded Lunar Outpost in 2017, he and his team wanted to find a niche with both high potential for growth and diversification, but one still small enough to avoid having to compete against the biggest in the industry.

“At the end of the day, we didn’t want to compete against Elon Musk, we didn’t want to compete against Jeff Bezos,” Cyrus said, referring to the heads of SpaceX and Blue Origin.

Instead, Lunar Outpost takes advantage of the primary innovations of those two companies, which has been to cut the cost of getting payloads into orbit by about 90 percent in some cases. The Lunar team decided to focus on transportation technologies beyond earth’s orbit, eventually landing on industrial robotics for use in extreme environments.

The company has also embodied Musk’s ethos to “move fast and break things.” The rovers made by the company certainly seem expensive, but they cost a fraction of those developed and sent into space by NASA, which have cost billions of dollars each.

“That’s what it’s going to cost if you have to have 99.99999-percent chance of success,” Cyrus said. “However, if you’re willing to accept an 80-percent chance of success, you can send dozens of rovers, dozens and potentially even hundreds of rovers for the same cost of one rover.”

That tradeoff, he said, would allow for much more work and science to be done on the lunar surface, even with a few broken down rovers. Then, as has been the case with SpaceX, data provided from the failures allows for rapid iteration and improvements on the next ones set for launch.

Cyrus has high hopes the rover being sent to the Moon in November will accomplish all its goals. But, he said if his rover is able to just successfully drive off its lunar lander, his team will consider that a success. They have three more launches scheduled in the next three years to try again.

Colorado as a hub

Cyrus said Colorado’s space community is different from the space and technology sectors in other places, like Silicon Valley or Boston.

“Those startup environments are very competitive,” he said. “Here in Colorado, it’s quite a bit different. It’s a very collaborative environment and that’s what I love about Colorado. It’s been a great ecosystem for our company to grow and thrive in.”

Bob Cone, chair of the Colorado Space Business Roundtable, said states including California, Texas, Alabama and Florida all have thriving Space industries, but that nowhere else has been able to foster innovation quite like Colorado.

“We have the highest concentration of aerospace employment in the U.S., maybe in the world, here between Fort Collins and Colorado Springs,” Cone said.

He said the state’s industry is well-diversified, with the largest companies having a firm presence all the way down to the small startups like Lunar Outpost, which currently has about 70 employees.

A 2023 report from the Metro Denver Economic Development Corporation notes that more than 60-percent of Colorado space companies employ fewer than 10 people.

With costs coming down and advancements in everything from materials and electronics to artificial intelligence, Cone said that of any time in his more than 30-year career, the period now feels like a new space renaissance.

“I have never witnessed the confluence of really positive effects for an industry — in this case aerospace — like I have in the last five to 10 years, across the board,” he said.