As the 130th anniversary of the birth of renowned actress Hattie McDaniel approaches, a new effort is underway to commemorate her life, including the Colorado ties, of the first Black person to win an Academy Award.

“She did a lot, and I’m finding out all the time stuff that I didn't know,” said her great-grandnephew Kevin John Goff.

Now in his late 50s, the Los Angeles transplant recently moved to Colorado to find out more.

“There's still so much to unpack. So I know when I get into the family as a whole, there's gonna be this treasure trove of information and it's gonna take some time to really kind of sort through it. It'll be a long-term investment.”

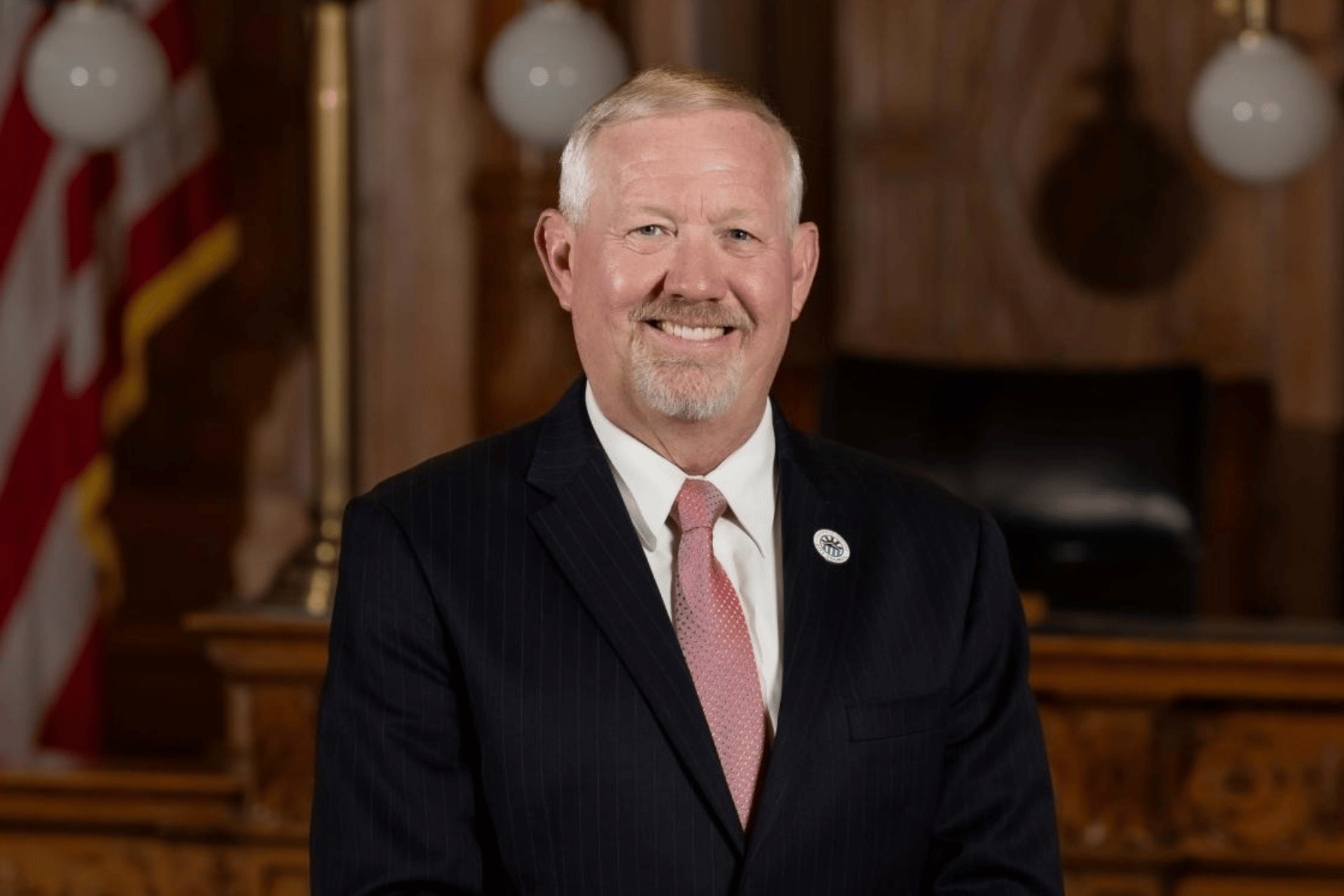

Goff had been living in California. But during the pandemic, when Fort Collins mayor Jeni Arndt named June 10 “Hattie McDaniel Day,” in 2022, he and his wife came to town to bear witness.

Realizing how much information there was to find out about his famous ancestor in Colorado, he and his wife, whose work is remote, decided to make Fort Collins their home.

“So we came down, accepted the proclamation, and while we were down here, we were planning our next move, and we decided to move here for that next adventure,” he said in a recent interview.

Hattie McDaniel led a life full of adventure.

She was born June 10, 1893, in Wichita, Kansas, the thirteenth and youngest child in her family. They moved to Ft. Collins when she was a child, then to Denver when she was in her teens.

She spent two years at Denver’s East High School — from 1908 until 1910. In the 1920s, she sang lead in the Melody Hounds, a touring jazz group in Five Points before the touring life took her to Tinseltown.

Her time in Colorado left its mark. In 2008, she was one of the first 30 people inducted into the East High Alumni Heritage Hall. Two years later, in 2010, she was inducted into the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame, a select group that only admits some nominees. Chairperson Barbara Beckner said McDaniel is in the company of NASA astronaut Susan Helms and former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.

“She truly was, you know, a trailblazer in her own way, in those early days with what she was able to accomplish as an African American actress,” Beckner said.

Some would argue McDaniel blazed a trail. But others, including members of the NAACP of that era, thought she was pandering by playing roles that diminished Black people — in a time when there were few opportunities to play roles that didn’t.

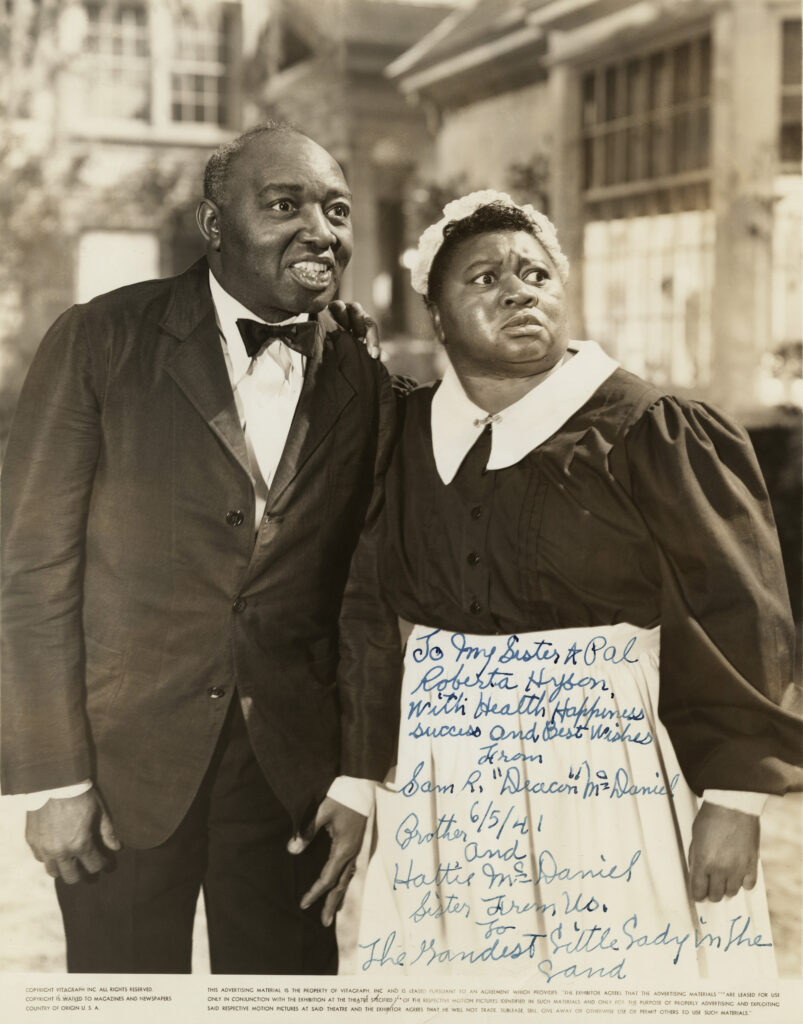

Her most memorable film part was that of Mammy in "Gone with the Wind," which came out in 1939. In 1940, she won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her portrayal — which she elevated with a twist.

Mabel Collins, the partner of another McDaniel descendant, spoke to a Hollywood Reporter interviewer 15 years ago and pushed back on the argument that McDaniel somehow diminished Black people through her roles.

“Every picture, every line she played, it belonged to her,” she said. “She knew she was supposed to be subservient, but if you’ve seen her pictures, you know she did not deliver a subservient line. She would take over and it would become a Hattie McDaniel picture.”

No amount of take-over put her in the same spot as her white peers. She wasn’t allowed to sit with the cast of "Gone with the Wind" when she won the Oscar. Nonetheless, archival footage shows her walking to the stage, back straight, head high, to tearfully accept her award, saying it made her feel very humble and that it was one of her finest accomplishments.

Later, she appeared on radio, and later, in the TV sitcom, “The Beulah Show” as a maid for a white couple. Her role was similar, taking care of the couple while making some quippy comments. She got $1,000 a week — a fortune in the '40s and '50s.

She died in California from breast cancer at the age of 59. She had been widowed in her early 20s and then married three more times. She didn’t have kids, but she helped raise her grand-nephew, Goff’s father.

“Hattie used to babysit him, so technically, my dad was her child, because she never had kids of her own,” he said.

Although McDaniel’s death preceded Goff’s birth by about ten years, he grew up watching movies in which he’d come across McDaniel relatives — not just Hattie. Hattie’s older siblings Sam and Etta were also active performers who appeared alongside the likes of Elizabeth Taylor and Clark Gable. The four racked up hundreds of credits in the ’30s, '40s and ’50s, which created memories for Goff:

“I’m watching these movies and I’m starting to notice, ‘Wait a minute, that’s my Uncle Sam right there with Humphrey Bogart in this film,’” he said. “‘Oh wait a minute, that’s Etta. Wait, there, there’s Hattie!’”

Now Goff is honoring a commitment he made to his father to keep her legacy alive, by diving into family archives to research Hattie McDaniel’s story.

He’s raising funds for production, and trying to find a writer – that part’s been tricky since the writer’s strike. The story is continuing to take shape as he continues to do research.

Rather than telling a Hollywood story, his take will be more intimate, “reflecting back on some of the things away from the movie set, photos of her in a normal setting, and family stuff,” Goff explained.

“Denver is like the newest part of my journey as far as her life is concerned,” he said.

What he admired most about McDaniel wasn’t what she did on screen, but off.

“Here’s this black woman in the 1930s and ‘40s. She wasn’t invited to the premiere of her own film in Atlanta because she was Black. Her neighbors wanted to get her out of her own home that obviously she could afford because she was Black,” Goff said. “But while all those things are happening, she’s mentoring people. She’s entertaining the troops during World War II. She’s raising war bonds and funds for the war.”

One place Kevin John Goff can go for some McDaniel archives is the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery, which came across a photo of her in elementary school and a few other pieces of family memorabilia.

Lesley Struc, curator of the museum archives, said she thinks the documentary could turn up even more details to round out her story. She said the museum is a quick five-minute walk from the McDaniel family's former home on Cherry Street, where, a few years ago, a plaque was placed to commemorate that the McDaniel family had once lived there.

“It would be great to see just a really lovingly created documentary from a family member,” she said. “It would be wonderful, if, through the course of this documentary, more information came to light. I'm hopeful that the more people know about it, the more they'll maybe be inspired to look through their own stuff and maybe find some historic documents that would add to the story.”

Besides doing the documentary, Goff wants to shore up the McDaniel legacy in other ways.

One thing he hopes to accomplish: locate Hattie McDaniel’s Academy Award, which mysteriously disappeared from Howard University in the ’60s or ’70s. She had previously donated it to the famed historically black college in Washington DC before its whereabouts became unknown, Goff said.

He also said he knows there’s an unmarked grave or two in Denver’s Riverside Cemetery, where a few of McDaniel’s family members are buried, and he plans to get headstones for them. He’s also considering a podcast, and maybe even a book.

“There’s so much information that one documentary is not gonna capture the McDaniels as a whole, of course,” he said. “There are all these different pieces that are moving around. And I’m trying to make it all make sense and put it together.”