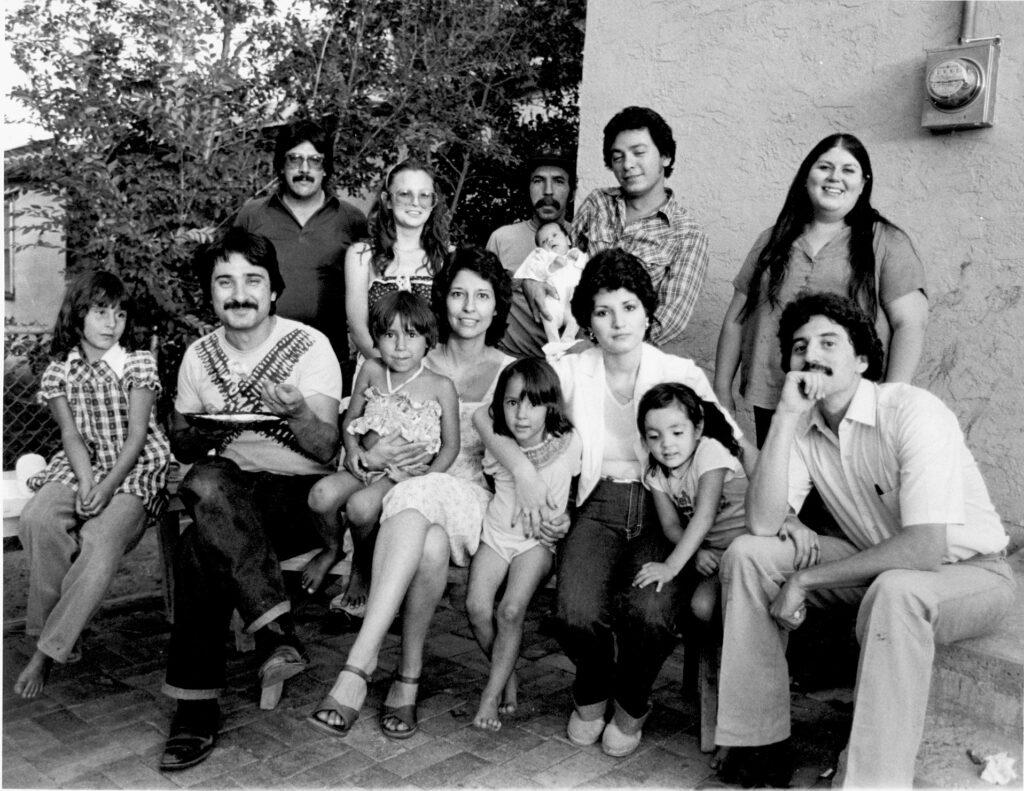

Back in 1976 a handful of young journalists launched a Pueblo-based Chicano newspaper. They called it La Cucaracha. These volunteers covered issues critical to their southern Colorado community. But by 1983 they stopped regular publication to focus on supporting their families. Now the ink is flowing again. The plan is to continue to publish La Cucaracha quarterly both digitally and in print and distribute it for free.

One of La Cucaracha's founders and current editor Juan Espinosa is an award-winning journalist who spent more than two decades at the Pueblo Chieftain. He spoke with KRCC’s Shanna Lewis about the paper’s history and its new incarnation.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

Shanna Lewis: What was the original motivation to launch La Cucaracha back in the 70s?

Juan Espinosa: There was a phenomenon known as the Chicano movement, which was really the Chicano Civil Rights Movement. When I got involved in journalism, I recognized we weren't getting a fair deal in the mass media across the board — television, radio, and newspaper coverage was very biased and didn't really understand us very well. We weren't well represented. So it became a goal of mine to try to create that representation in the media.

Lewis: What specifically were you observing that was unfair?

Espinosa: The first Chicano newspapers I saw were out of northern New Mexico or Albuquerque. They always had pictures of some poor guy that was beat up by the police, left bloody, and in some cases killed. (The photos) were shocking. I guess I assumed when I first saw those, that that was an exaggeration or it was an exception.

The more I got involved in the Chicano movement, the more I realized that those cases were happening all over. I witnessed a few incidents of police brutality when I was growing up, but it didn't really register for years later. Then I recognized what the men of my dad's generation were saying when I was a kid — that the police department was treating us differently than everybody else and they were more brutal. The fact that the other mass media didn't take it as a serious issue, I knew meant we had to do something for ourselves.

Lewis: Why have you decided to bring the newspaper back now?

Espinosa: It's probably needed now more than ever. We're part of the mix that's serving this community in terms of news delivery. What I want to do with La Cucaracha is represent our community, the Chicano community, but I also want to do a lot of mainstream reporting that is not being done by anybody. So I think if you picked up a recent edition, you'd see by the variety of the stories that were reporting that we're not just a Chicano newspaper – we're a Chicano-run newspaper that's trying to report the most important news of our community.

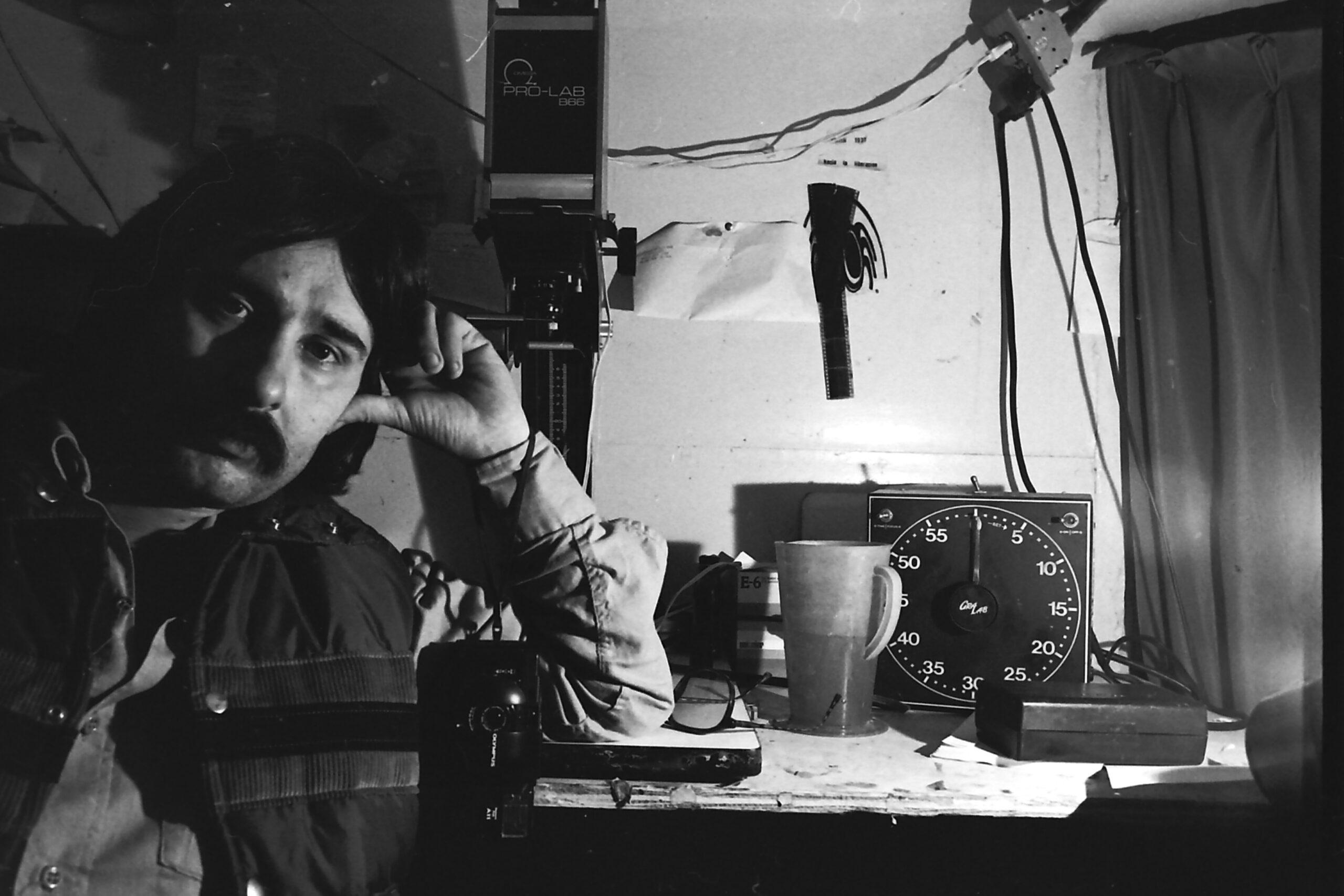

Lewis: Backing up a little bit, tell me what it was like to get La Cucaracha reported, written and published back in those early days.

Espinosa: I gotta tell you, our early staff were troopers because we had families to support. And one of the things that we didn't believe in was public assistance. We were being critical of the government and we found it inconsistent to ask the government to help us. So we didn't. I was eligible for food stamps for the first 10 years of my marriage and we never got food stamps once. I always worked at different jobs and everybody else did too.

On the weekend that we would do La Cucaracha, I would borrow a Selectric typewriter and everybody else would do that too. So we had a long table set up with all these electric typewriters borrowed from different agencies, and that's what we used to typeset and write our articles. I would get off on a Friday afternoon about 5 p.m., and we would work through the night and then we'd work all day Saturday. We’d frequently work through the night on Saturday and sometimes through Sunday night into Monday morning. And we did that for almost the whole eight years that we published.

We had also had a little group of supporters that would start coming through the door on Friday afternoon with pots of food – menudo and stacks of tortillas. Their mission was to make sure that we didn't have to take a lunch break and go someplace to eat and spend money. It was a real community effort.

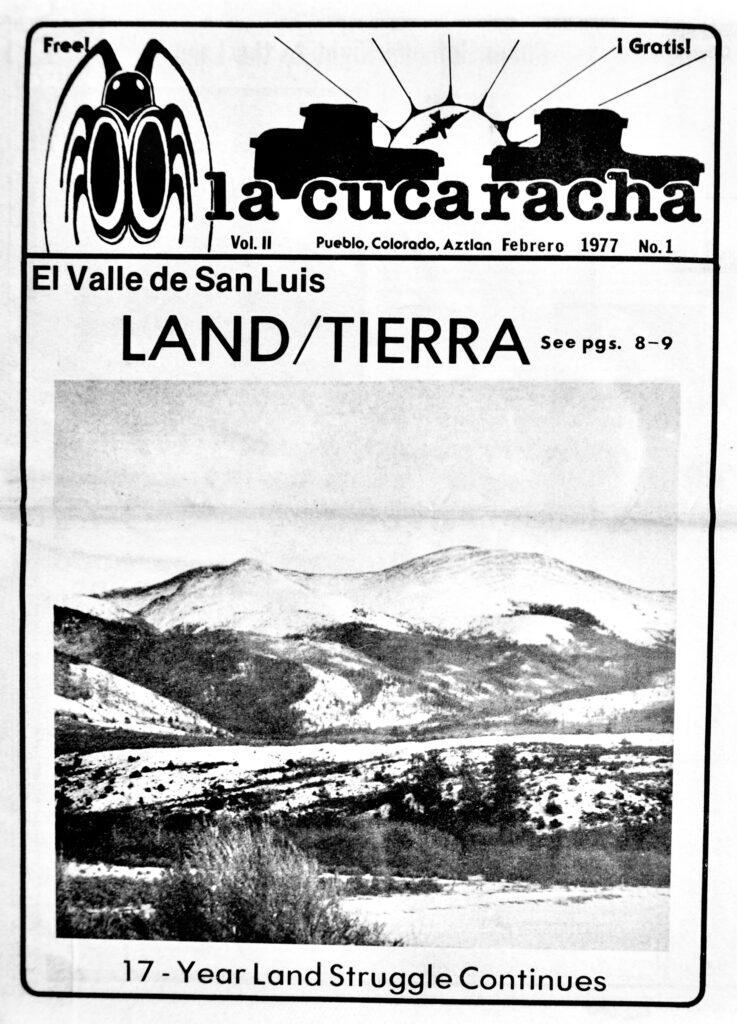

Lewis: What was one of the most important stories that La Cucaracha covered over the years?

Espinosa: The one that had the most historical significance is the land rights story out of San Luis. There was a large parcel of land, 77,000 acres, that was set aside for the community to use as a resource. It was considered communal land, but it passed into private hands.

In 1960, Jack Taylor bought that ranch and he cut off all the roads. (The community) sued Jack Taylor for access, for their historic rights. The Colorado Supreme Court upheld the historic rights of the original settlers and their heirs. So now there's over a thousand people that have access to that ranch to use it the way it was traditionally set aside.

That story was being ignored by the mass media because Jack Taylor had a lot of influence and the people of the community that were fighting for their rights were portrayed as like bandidos that were trying to run this poor white guy off his land. It was just terribly one-sided. And I know we played an important role in that particular story and that's just one of many.

Lewis: Talk about the name of the paper itself, La Cucaracha. Why did you choose it?

When we were trying to name this newspaper I said we’ve got a song. We’ve got a song, La Cucaracha and we've got historical significance. Pancho Villa used to march his troops to the song La Cucaracha. He was one of the first military generals to use a train that would follow his troops with supplies, with ammunition, with feed for their livestock, with food and a little hospital operation. He called that train La Cucaracha.

Also, there was a popular book out at the time called Revolt of the Cockroach People that we were all reading. And I remember reading some reports that scientists were saying that if there was a nuclear holocaust, that life would be pretty well wiped out, except maybe things like the La Cucarachas, the cockroaches of the world.

So I thought, you know, no matter what happens, we're going to hang in there, we're gonna make it. So that was also part of our image, that we're gonna survive. Whatever is handed to us, whatever we have to deal with, we're gonna survive it and we're going to overcome it. So, I just said, let's just call ourselves La Cucaracha and that stuck.

Lewis: I understand that you guys applied a portion of that name to yourselves.

Espinosa: We called ourselves the Cucs [sounds like kooks] which is short for Cucaracha. So we became DaveCuc, JuanCuc, PaulCuc – we all kind of took it as our last name.

Lewis: In this new iteration, you plan to print paper copies for people who don't have access to the internet?

Espinosa:.There's something magic about a paper newspaper. I grew up with them and I love it. My favorite part of publishing is distribution. I just love handing a paper to somebody. And you know, the best thing is they say, “Hey, my dad used to read this newspaper to me,” or some of the old people say, “ I remember it. I used to read every copy.” So you know, there’s the gratification that we've been accepted and people are happy to see us back. The distribution is where it's at, because it really ties us all together and really creates a solid community.

Lewis: What niche does La Cucaracha fill now?

Espinosa: You know what the other sad thing is that the relevance is that many of the issues that we're dealing with right now today in Pueblo, Colorado and other parts of the country are the same issues that we were addressing back in the 70s. Not that much has changed. We have a lot of good success stories and we try to tell those as much as we can, but you know, for the majority of us, we're still in the low-income jobs. We have the lowest educational attainment, we have the poorest healthcare, and we need to continue to raise ourselves up and La Cucaracha is part of that.

Editors note: This story was updated to correct a typographical error and add more information about the paper's current editor.