In an apartment near downtown Denver, Ashley Ryan ran a small wooden baton around a Tibetan singing bowl and struck it once, then twice, filling the space with a clear, calming tone.

“Singing bowls,” she explained, “might be incorporated in a healing journey.”

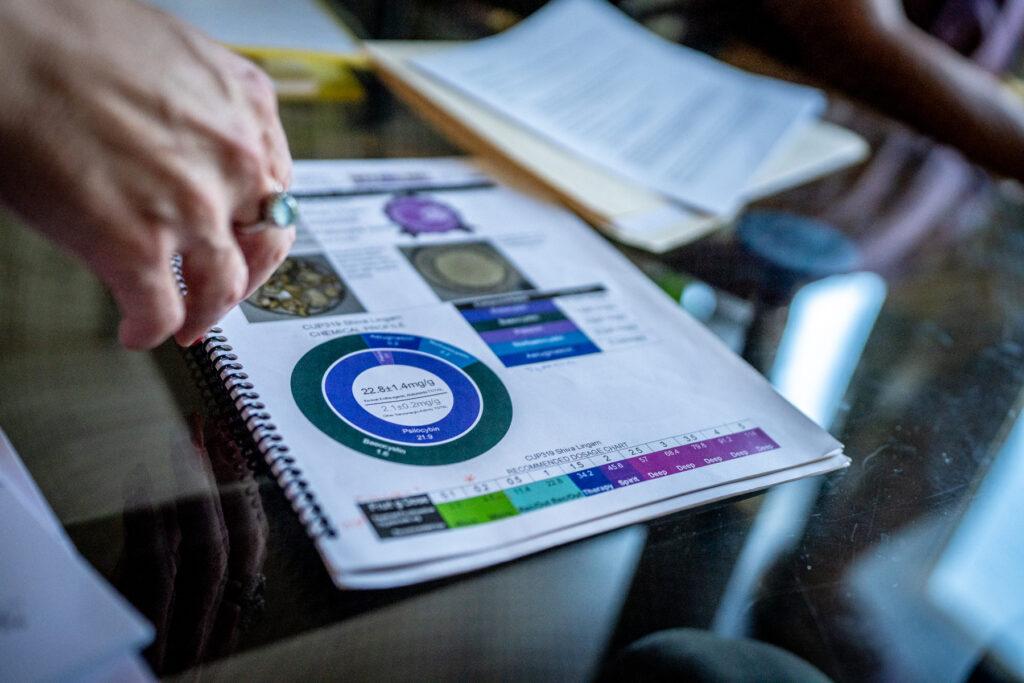

Ryan calls herself a psychedelic guide. The sound of the bowl is just one of a dozen details meant to make the loft apartment feel safe for someone who’s just eaten a batch of psychedelic mushrooms.

“I use guided imagery, yoga, reiki,” she continued, opening a balcony door that looks out on the rushing South Platte River. Some clients stay here in the loft, while others ask to go for a walk with her on Denver’s trail system.

Ryan is a former public school teacher who says she found happiness through her own careful use of mushrooms and now wants to help others. Over the last couple years, it’s become a part of her business as a meditation and spirituality educator. She’s now guided dozens of trips, for fees ranging into the hundreds of dollars.

“That includes not just individuals but couples, small groups of friends,” she said. And sometimes it’s just people she knows who want company on a psilocybin trip.

Ryan is at the forefront of Colorado’s potential new psychedelic industry — so far ahead, in fact, that the laws around what she’s doing remain confusing and unclear.

Last November, Colorado voters approved Proposition 122, creating the Natural Medicine Health Act, with the measure passing by more than seven percentage points. But the state is still well over a year out from issuing its first licenses for the psychedelic industry.

That hasn’t stopped early “gray market” practitioners like Ryan. One man in Denver is offering “Micro Monday” classes and supplies for mushroom microdosing. Others are growing mushrooms in closets and warehouses and “sharing” them broadly, including with practitioners like Ryan, with little fear of reprisal. Online searches quickly turn up numerous websites offering guiding services in the Denver area.

The proposition “gave us the opportunity to use our voice and to share the healing power of mushrooms with others,” Ryan said.

For now, state law allows for these kinds of unregulated activities with mushrooms and other psychedelic drugs. But these businesses may find themselves too far ahead of the curve: The state plans to launch a much more strictly regulated mushroom industry next year, and lawmakers are already trying to discourage informal operators like Ryan — with big changes coming as soon as July 1.

The paradox

Prop. 122 made two big, fundamental changes. Perhaps the best-known one, receiving much of the attention during the campaign, is that it will eventually allow for the creation of state-licensed “healing centers.”

The idea is that, in the future, people will go to regulated facilities and pay for a supervised mushroom experience with a professional who has been trained to certain standards, using mushrooms from a licensed cultivator.

But those state-sanctioned psychedelic sanctuaries are still a long way out. The first licenses may not be granted until late in 2024 or beyond.

In the meantime, though, Prop. 122 has already made a big change that has opened the door for people like Ryan: About six months ago, Colorado removed many of the criminal penalties around possession, cultivation, use and “sharing” of psychedelic mushrooms and other psychedelic drugs like DMT.

The change in the law allowed Ryan to start providing people with access to mushrooms and her time as a psychedelic guide — very similar, in concept, to what the regulated healing centers will eventually offer. The only rules at present are that mushroom-sharing guides can’t pay for advertising, and they have to share the drug, rather than selling it.

That relatively lax approach has tempted people to go public with their psychedelic ambitions. It’s impossible to put a number on it, but several people in the scene said it’s grown significantly since decriminalization, into the dozens or perhaps hundreds of people offering mushrooms and related services around Denver alone. (They also reported an increasing number of people who are explicitly selling mushrooms, which remains a felony but is perceived as being less legally risky now.)

Ryan’s partner, Jimmy Smrz, says that the measure approved by voters, Prop. 122, intentionally allows for small-scale psychedelic services to operate without getting licensed.

“As long as it was a small scale and done in a private residence, you would be able to do essentially what the regulated side wants to do. But you didn't have the oversight,” he said. He’s a libertarian, so he prefers this option.

But state lawmakers don’t see it that way — and they passed a law this year that could clamp down on gray-market psychedelic businesses like Ashley Ryan’s.

“There's a challenge in that we are setting up a regulation system, but then also allowing people to do similar activities through an unregulated system. And that's not normal. That's not usual,” said Senate President Steve Fenberg in an interview.

The change

A new state law with new requirements for psychedelic drugs, Senate Bill 23-290, goes into effect July 1. It will ban not just paid advertising but all forms of advertisement for unlicensed guides who are offering mushrooms, among other restrictions.

The idea is that practitioners like Ryan can still offer paid services, but it should be closer to a hobby or a service for one’s friends or immediate community. Fenberg doesn’t want to see people “soliciting” business without a license.

It’s untenable, he said, to have unlicensed, unsupervised people offering the same services that will eventually be sold through tightly regulated healing centers.

“It was important to us that we didn’t totally cut off personal use and sharing,” he said, “but we also wanted to make sure that we had fidelity to the fact that Proposition 122 asked the state to regulate these services.”

Psychedelic advocates are split on the changes. Ashley Ryan fears that she’ll have to strip down her website and go silent about her work.

“I’m wondering what's going to happen next as much as everyone else,” she said. “With the new regulations for community healing, I see it as going underground again.”

Once a Democrat, she said this year’s lawmaking process left her so frustrated that she re-registered as a Republican. Indeed, some Republicans objected strongly to the changes, with Rep. Ron Weinberg saying that the state was veering away from voters’ intent.

“They are [currently] doing it responsibly behind closed doors. Nobody knows it’s happening. Now you’re having the bloody government get involved, and that is only going to create incident,” he said.

Other Republican lawmakers, however, complained the law isn’t restrictive enough, in part because it doesn’t let local governments set tighter rules of their own to slow the growth of the legal psychedelic industry.

The new law also creates a misdemeanor crime for “unlicensed facilitation,” although it still allows for “bona fide” support services. That’s left some unlicensed guides like Ryan unclear on what exactly they are allowed to do. And that confusion may not be fully answered until the state finishes drafting rules and regulations for the psychedelic industry.

Tasia Poinsatte, who worked on the campaign for Prop. 122 and is state director of the Healing Advocacy Fund, largely approves of the new Senate bill, saying it’s mostly a way to fix smaller issues with the proposition. (It makes a number of other changes, like defining criminal penalties and giving the state more time to set up its licensing system.)

Poinsatte said the state is trying to balance the regulated industry and the unregulated world.

“How do we put in place the pieces [for regulated access] while still making sure that people have this level of freedom to engage responsibly within their own contexts and communities?” she asked.

Kevin Matthews, another of Prop. 122’s main advocates, said that the two worlds can coexist, with plenty of demand for both licensed and not-so-official services.

But Democratic Rep. Judy Amabile fears that the unregulated market is taking off before the state can weigh in on what a safe psychedelic service looks like. It will be more than a year before the state’s psychedelic advisory board makes recommendations about training and licensing, and the first licenses may not go out until the end of 2024.

“My preference would have been to stand up this regulated framework first and see how that goes before we also had the unregulated framework,” said Amabile, who cosponsored the implementation law with Fenberg. Nonetheless, she said, lawmakers are trying to work with the system that voters created.

Travis Tyler Fluck runs an unregulated microdosing event called Micro Mondays. For $30, participants attend a lecture on how to incorporate small doses of mushrooms into their lives. He also gives them a month’s supply of mushrooms, free of charge.

He’s not too worried about the new law — he plans to frame all of his activities as educational, potentially avoiding the prohibition on advertisement. But he said lawmakers and police should largely leave the unregulated market be.

“The most intelligent thing that Colorado can do is foster an environment of motivating people to be as visible as possible with what they're doing,” he said. “Because most of this work is no stranger to the underground. And that's where a lot of harms are done.”

Psychedelic advocates believe that experiences with the drugs can help resolve mental health issues, arguing that they’re generally non-addictive and pose little immediate physical risk to one’s health.

Early research on the therapeutic promise of psilocybin is promising — but researchers also warn that a psychedelic trip can turn frightening or even traumatizing, potentially catalyzing or worsening psychiatric conditions.

“The quality of the studies is variable,” said David Hellerstein, a professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University, in an interview with CPR News last year. “The findings are interesting and encouraging. But there's a lot of holes and a lot of gaps.”

What will 2025 look like?

Colorado is stepping into unknown territory. Only one other state, Oregon, has decriminalized mushrooms on a statewide basis, and the results aren’t obvious yet.

In Oregon, the new law allows for supervised mushroom services, similar to Colorado's healing centers. The first opened just a month ago, with prices for a single trip running more than $3,000, according to Willamette Week.

Oregon’s regulated system comes with strict requirements and costs for facilitators, and Colorado is likely to follow suit — requiring not just training and licensing, but also multiple hours of supervision for each client.

“You’re looking at hours of somebody’s time who is trained and licensed,” Poinsatte said.

She thinks prices will come down somewhat, eventually — but a question remains of who will be able to afford to participate in the regulated market, both as clients and as facilitators.

Unlike with cannabis, there will not be any way to legally buy the drug in a retail setting. Instead, Coloradans will have to choose between a highly regulated, expensive clinical service, the likely cheaper unregulated market, and just using mushrooms recreationally on their own.

Fluck worries that the powerful players in any new regulated market will have an incentive to push the state to crackdown on their gray-market competition.

“Once you allow industry in, and we're seeing this with medical cannabis, you know, the lobbyists come in and start chipping away at these personal freedoms,” he said.

The mushrooms themselves are becoming more common, too

It’s not just a matter of unregulated guides and psychedelic educators. The mushrooms themselves appear to be easier to obtain since decriminalization. A search on Facebook Marketplace revealed dozens of listings of what appeared to be psychedelic mushrooms for sale, often accompanied by photos of large tubs of fungus and links to private messaging services.

In interviews with CPR News, online sellers said there’s been an upswell of people growing and distributing the drug with relatively little fear of punishment — along with some scams meant to lure aspiring psychonauts.

The act of sale remains illegal, but it’s harder to get caught now that the criminal penalties for growing and possession have disappeared, they said. Additionally, the drug is relatively easy to grow, requiring much less space and energy than cannabis. Some worry that will lead to a sprawling, unregulated market with few controls on quality.

“This entire regulated system will be great for … the quasi-medical aspect of it, but the recreational aspect is just going to be the Wild West,” said Tim Lane of the Colorado District Attorneys Council. “There’s so much room within the statutes to cultivate and share that there [effectively] is no regulation.”

In Denver, which approved mushrooms several years before the state, it’s too early to tell just how much decriminalization has changed the drug market, according to the Denver Police Department. Psilocybin-related criminal charges remain relatively rare, with just a few dozen confiscations reported in the years since the city enacted a local form of decriminalization, and no clear change since the statewide law took effect.

The state faces not just two sides in this debate, but an “octagon of interests,” Rep. Amabile said. For now, Sen. Fenberg argues that lawmakers have found a balance that allows the two very different models of mushroom access to remain.

Part of his goal, he said, is to avoid inviting a crackdown by the federal government.

“The sort of unspoken agreement since marijuana legalization is as long as you were regulating it in a mature and professional manner to avoid worst case situations, the federal government generally is going to assume that you are doing your part in not allowing [a federally illegal drug] to get out of control,” he said.

While the laws may be in place, Colorado’s psychedelic journey has only begun.