“We are the unbreakable woven thread.”

“They want red white and blue, but they don’t want me.”

“Fitting into American society, but then, also not.”

“There is no right or wrong; it’s about me and you….”

Words of resilience, marginalization, trepidation and community were spoken when about 50 people showed up on July 1 at a spiritual center in Arvada to brainstorm lines for what eventually became “I Am the Bridge: A Poem By All Of Us.”

It’s a four-page poem with contributions from local Native Americans, Asians, Hispanic people, Jewish people, European people, Black Americans and African immigrants. It will be performed by seven people, one representing each of these groups, at the Arvada Center on Saturday evening.

It was the brainchild of 52-year-old Senegalese-born Papa Dia, who came to Colorado in the 90s. After stints as a Tattered Cover bookstore worker, and a bank teller who grew to become a senior banking officer, he founded African Leadership Group, whose mission is to create opportunities for people of different cultural groups to get to know each other.

“We have always been an inclusive organization, because for us as African immigrants, in order to professionally integrate into the American society, we need to work with people from this country, right?” Dia said.

The organization’s African members recognized the absence of a relational bridge between Black people born in the U.S. and Black people born in Africa who later chose to come to the U.S.

“We are both Black, but our journeys are totally different…for somebody like me, I’ve never been enslaved,” Dia said. “I don’t know how it feels to be oppressed. I don’t know how it feels to be a minority, because where I’m from, everybody looks like me, everybody sounds like me.”

That made it hard to relate to the experience of Black Americans, he said.

“We always have a hard time to understand people from the Black [American] community, why [some] could not emerge from [the] environment they were put in, right?” Dia said. “We don’t understand quite enough the system that has been put in place from generation to generation to really prevent them from elevating themselves, right?”

That has led to barriers where bridges could be.

“There’s always been a gap and a friction between the two communities; very judgmental toward each other,” Dia continued. “So I wanted to do something about it. I wanted to create a space where we just come together.”

Uniting through poetry

His concept was to come together through poetry – not just African Blacks and American Blacks who don’t really know or understand each other, but people from other minoritized groups also ignorant or uncertain about other groups they are not a part of.

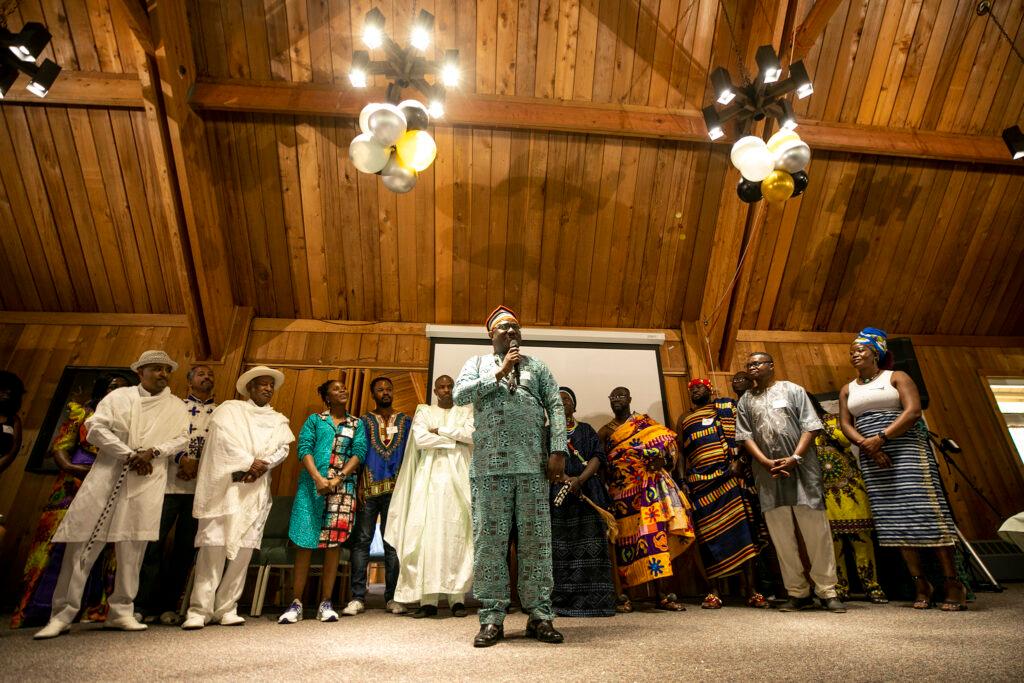

He came up with the idea for a poem that different groups could compose together. He reached out to people he’d cultivated relationships with – including local Black American slam poet Theo Wilson, Colorado State Attorney General Phil Weiser, and head of the local Anti-Defamation League Susan Brody. More than half the room was filled with Black people – Americans Dia had also built connections with, and people whose journeys brought them from Ghana, Cameroon, Senegal and other African countries.

In all, there were fifty or sixty people. Some, including Native Americans and Africans, were wearing traditional clothes; others were speaking with accents reflecting their first languages. On that hot summer morning, they’d agreed to be part of the creation of a poem about unity, something Dia, 52, had imagined one day and believed he could make happen. His goal with it is for it to be mounted on the walls of the offices of elected officials, for it to go viral, and for it to serve as a model other people can get together and create, and, in the process, find connections that will help relationships to form.

“We can elevate and do great things. My hope is as a person, I know how to break barriers. I know all these people, I know all these communities. I work with all of them,” Dia said. “So I gotta create a platform for other people to see the value, and hopefully they will leave just working with even one other community, so we can all do our part in bringing people together.”

Sharing language, food and expressions of joy

The day was broken into thirds: first, everyone introduced themselves as part of the group they fit into. One group used a song to do so, others spoke about the clothes they had on. A white man joked, “I’m wearing the traditional American pant: the jean!”

Talk of clothes highlighted the difference between Black Americans and African Americans. One Black American woman noted in her intro that Black Americans have no traditional clothing, after they were stripped of the cultural identity of which clothing is a part, because of slavery. Meanwhile, one Ghanian man was wearing a garment that went over one shoulder, leaving the other exposed, and was printed in with vivid graphic colors and patterns that have meaning and are to be worn for specific reasons, such as celebrations.

The African immigrant group’s introduction included a high-pitched sound, “LEE-LEE-LEE-LEE!!” As one member of the group explained, it’s called ululation (OO-loo-lation), and, she said, “It’s how we express our happiness.”

The Native American group included in their introduction an honoring of the tribes upon whose indigenous lands the meeting was taking place. The Jewish group taught a traditional wedding dance that began with putting on a yarmulke as a demonstration of respect and humility, and ended with everyone in the room yelling “Mazel Tov,” an expression of congratulations in Yiddish. When attendees moved chairs out of the way and started grape-vining around in a circle, barriers were breaking with each step.

Then it was potluck time in the lower level, with a steaming plate of Ethiopian cabbage and lentils on one table, a casserole of noodle kugel, a sweetened version of pasta typical to some Jewish traditions, on another. One white man found out samosas, part of Indian cuisine, exist in some African cuisines as well. “Get a plate, try one,” he was told, to which he mumbled a cautious, “OK.” During the meal, people also chatted with members of their groups about what lines they wanted to submit.

Connecting to common themes

After about an hour of pot-lucking and idea-gathering, the final third of the day began. Everyone was called back upstairs. The remaining part of the day was to be spent in what felt like a very loving auction, with the local slam poet Wilson, who was also part of the American Black affinity group, as the caller.

“Can we sit with our affinity groups? I see my Jewish Americans. I see the foundational Black Americans over here. I see my African immigrant family over here!,” he said jubilantly, as people found seats with their co-writers. “Ya’ll look amazing from this angle! Give y’allselves a round of applause real quick!”

Then he explained what would happen next: each group would get a chance to go up front and say the lines they’d come up with. Then Wilson said he wanted feedback from everyone else. “What really resonated with you? What rung a bell?” He’d use the feedback to choose which lines would go into the poem.

As someone from each group went up, the common themes were so strong that on several occasions, the rest of the room began yelling and screaming their agreement, their approval, and their identifying with an experience from members of other groups, just a few hours ago perfect strangers, were also having.

When a member of the Latino affinity group went up front, with an earnest Spanish accent, he spoke about honoring his ancestors, migrating around the world, finding new homes, and building communities to survive the rejection inherent in the immigrant experience. Everyone was paying silent respectful attention, until he got to the line: “Red white and blue, but they don’t want me!” and the room, particularly where the Black Americans were sitting, erupted with whoops of agreement as they identified a shared experience of being shunned from inclusion in the full American experience.

“He said, ‘red white and blue but they don’t want me’!” repeated Wilson, as the rest of the room called out, “Yeah! Yeah! There you go!”

That’s when Wilson introduced the verb chunk, as in, “I’ma chunk THAT!” That’s what he would say when the collective gave universal approval to a submitted line, meaning he was going to take that chunk – out of the totality of the lines submitted – and find a place for it in the collective poem.

Finding the chunk

The process continued as other groups went up front to share what they’d come up with. Words like “We stand shoulder-to-shoulder,” “Please remember we are family,” and “We are the indestructible woven thread,” were some of the favorite bars composed by the Native American group; they got chunked into the draft of the collective poem as well. Other groups echoed standing side by side and being both unbreakable and a combination of different ethnicities that wove them together.

The Jewish group’s lines, “Am I safe here, and for how long?” and “If I am only for myself, who will be for me?” were words applicable to Black people, immigrant or not, who’ve heard names like Amadou Diallo and Botham Jean, both from Black immigrant families who’d chosen to come to America, only to be killed by police.

When the European group, about a half-dozen strong, was called upon, the room quieted. It wasn’t a shared common experience, but instead the acknowledgment of a unique one, that got the group going as soon as a woman with a brown ponytail spoke the words her group had come up with:

“We are European American. We walk in the room white with a lowercase w. With a knapsack full of privilege. We have capitalized, consumed, colonized and exploited Earth and people and called it freedom. . . That is the barrier we will break. Our bridge is rooted in recognition and restoration. Recognition of real justice and universal humanity …Our bridge is rooted in listening and learning to the pain of the earth and the suffering of her children. Learning to bravely engage in important and urgent conversation … celebrating the beauty and richness found each day in unity.”

She spoke words of humility that people with dark skin – who dominated the room – probably had never heard a white person utter aloud. Of those lines, there was to be no chunking. When she finished, one person, then a few, then the whole room, chanted what part they felt belonged in the collective poem: “The whole thing! The whole thing! THE WHOLE THING!”

The Asian group consisted of just a few people, including Hayne Kang, who had played a haeguem, a two-stringed vertical fiddle used in many traditional Korean musical genres, during the introduction, and Becky Hogan, who had handed out sushi during lunch. Earlier, Dia had spoken about what their group pointed out: several nationalities (theirs included Korean and Afganistani members) being represented in one affinity group.

Lines they submitted touched on ways their appearance and societal expectations made them different and held apart from other minoritized groups – as well as how some of the dignity found in their cultural values made them similar.

Their bars included these words: “We are living courageously and creatively . .. I am Asian American, with hair as black as ink, and eyes like coal . . . but everything around us looks light. .. We are small in stature, but we have hearts the size of giants.. . . breaking the stereotypes of the model minority. . .”

The University of Texas at Austin Counseling and Mental Health Center defines the model minority as applying to Asians, “who have often been stereotyped as . . . smart (i.e., naturally good at math, science and technology), wealthy, hard-working, self-reliant, living the ‘American dream,’ docile and submissive, obedient and uncomplaining and/or spiritually enlightened and never in need of assistance.”

Their lines seemed to push back against the barrier the expectations of the so-called model minority placed on them by separating them from minoritized groups; they also leaned in to the bridge that connected them, even in marginalization, to others through highlighting a vision of commonalities bonding them with the collective: “Discipline, hard work and respect are the hallmarks of the Asian community - - virtues we share with the very best of humanity.”

Once everyone shared their lines, had some new foods and heard common themes, they were ready to leave in a cloud of freshly broken barriers, and their work was done.

But poet Theo Wilson’s work was just getting started. With much more material than he could use, he began the task of pulling the most agreed-upon lines from the submissions and turning them into a poem. It would be recited not by one person. Instead, he noted in the margins of the four pages who would say what lines. Some would be spoken by the representative of the group who came up with it, but in the case of lines everyone felt connected to, such as “Still we rise!” everyone on stage would say it in unison.

“OK, one, two, three,” he began during the rehearsal held in an Aurora event center last Sunday attended by at least one member of each of the seven groups. He spoke the opening lines from the Black American group, and cued other groups when they were supposed to chime in. Some people were still in the process of memorizing, and he offered suggestions of how to memorize: record it, he said, and play it on earbuds over and over until it became second nature.

The rehearsal ended after a couple of hours, all in preparation for the capstone event. The poem debuts at the Arvada Center Saturday night as part of the Center’s “Day of African Culture,” also featuring a fashion show and musical performance by Senegalese artists.

So did it all go according to Papa Dia’s plan? In a telephone interview after the brainstorming session, he said it surpassed his expectations, while at the same time meeting the vision he’d had all along, “Oooh! I am so very excited!”

He’s going to post videos of the poem’s creation and recitation on his YouTube channel and share it with whoever is interested. “Maybe after this, something else will come out of it, right? I’m just doing my part planting this seed… My goal is for other people from other states or other parts of the world to say, ‘Wow, look what they did in Colorado,’ and hope that they can try to do the same thing.”

The Day of African Culture takes place at the Arvada Center on Saturday, Aug. 5 and starts at 3 p.m. with a community celebration and the poem reading at around 7:30 p.m. Tickets start at $20.

Editor's note: This story was updated on Aug. 7 with additional information.