A hailstone that fell in Yuma County on Aug. 8 has shattered the state’s current size record, according to measurements taken by the National Weather Service and other meteorologists on Monday.

The large chunk of ice measured 5.25 inches long on the day it fell. A storm chaser picked it up on the side of a road between Kirk and Idalia following a severe storm that produced several tornadoes in Yuma.

The chaser documented its size with a photo, tossed it into a cooler and transported it to the nearest NWS office in Goodland, Kansas.

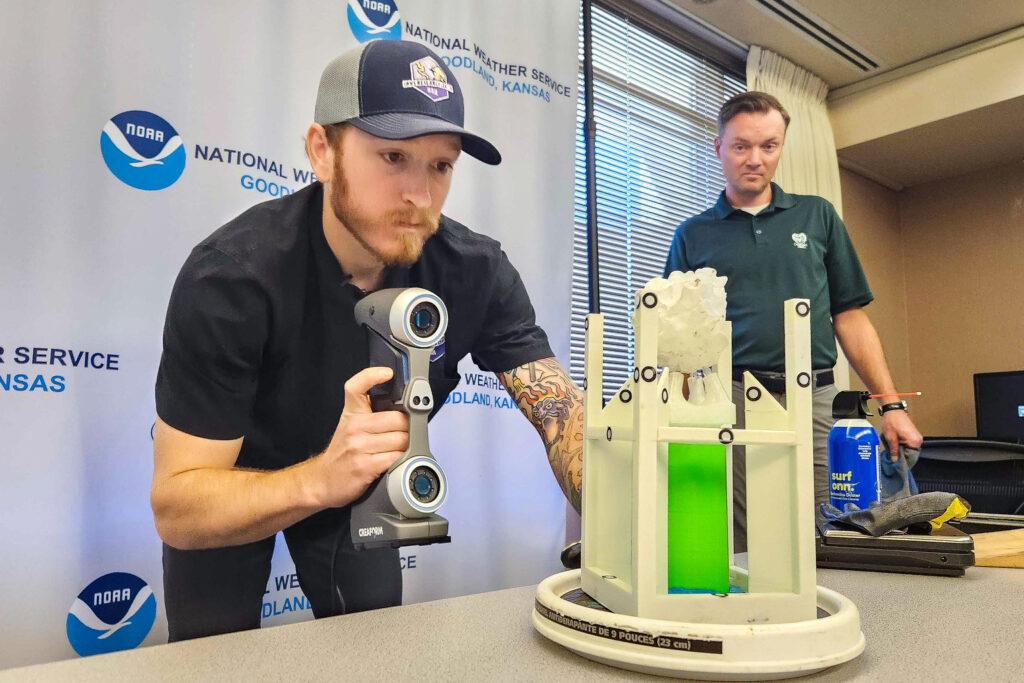

State climatologist Russ Schumacher and a meteorologist from the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety, a nonprofit that studies hail, met at the NWS’ Goodland office on Monday to record the hailstone’s measurements.

Schumacher put on a pair of gloves to handle the stone, so it wouldn’t melt more than it did during transport to NWS.

“There she is,” he said as he took a bag holding the stone out of a freezer.

The hailstone melted slightly during its journey, but a review of a photo taken the day it fell, plus additional measurements taken by the experts, confirmed it was longer than the previous record of 4.83 inches.

“It’s legit,” Schumacher said.

The results are technically considered preliminary until a state panel of meteorologists gives it the thumbs up for record-keeping purposes, Schumacher said. That process should wrap up over the next several days.

The meteorologists gathered Monday and scanned the stone with a sensor to create a virtual, 3D copy of it. They weighed it, then measured the circumference and diameter.

The hunk of ice clocked in at 7.29 ounces – slightly heavier than a billiard ball.

The measuring spectacle drew a small crowd of NWS staff and family members from Goodland. Jesse Lundquist, a forecaster, brought his 8-year-old son Ethan to watch.

“It’s pretty big,” Ethan said. “I haven’t seen one that big before.”

The large size served as a reminder that people should take NWS warnings about storms seriously, Jesse said.

“The storm that produced it was one of the most intense I've seen in my time here at the Weather Service,” Lundquist said. “It’s an example of just how important it's to have a plan ahead of time of where to go when severe weather is around so you're not dealing with something like this as it happens and trying to figure out where to go.”

That was the situation at Red Rocks Amphitheater in June, when a hail storm pummeled attendees of a Louis Tomlinson concert. The chaotic scene drew national attention due to its sudden onset and severity.

Hail forms when wind carries raindrops high up in the atmosphere, where they freeze. Stronger storms can keep hail in the sky for longer periods of time, leading to larger stones that reach the ground.

Colorado has historically been a hotspot for hail due to the region’s elevation. Hail storms have cost billions of dollars in damage to homes and businesses in recent years, and led to human and animal injuries.

Hailstones as big as the record-breaking one are extremely rare. The state probably sees a handful around its size fall each year, but most never get recorded, Schumacher said.

“It’s difficult to measure hail because it melts so fast,” he said.

Climate change doesn’t mean Colorado will start to see 5 inch hailstones regularly, Schumacher said. But as it continues to reshape global weather patterns, the severe storms that produce large, dangerous hail could become more common.

“Research that's been done up to this point does point towards a shift in hail from maybe less small hail,” he said. “Because if it's warmer, some of that small hail will end up melting before it gets to the ground.”

The hailstone that fell on Aug. 8 will remain at NWS’ Goodland office for now until the entire record-keeping process is finished. After that, the Colorado Climate Center and NOAA will determine where to store it permanently.