Carbon dioxide isn't the only climate-warming gas that's reached record levels in the last few years.

Scientists are now racing to explain what's causing methane — CO2's potent sidekick — to build up in the atmosphere at an alarming pace. That's especially concerning because the gas packs a short-term punch, trapping 84 times more heat than carbon dioxide in the first 20 years after its release.

Methane is also a tricky problem due to the variety of natural and human-made sources. The invisible gas seeps out of landfills, wetlands, cow guts and oil and gas operations. That makes it far tougher to pin down than carbon pollution, which can usually be tracked to the nearest smokestack or tailpipe.

A leading climate group now has a high-flying plan to help untangle the mystery and advance its policy goals.

Early next year, the Environmental Defense Fund plans to launch MethaneSAT, a $90 million satellite built to hunt global methane emissions with unprecedented precision. The results will be published online to hold corporations and nations accountable to their climate pledges, says Steven Hamburg, EDF's chief scientist.

"It's not just that we're going to produce data. We're going to build an advocacy team to ensure action is coming forward as a result of this increased transparency," Hamburg said.

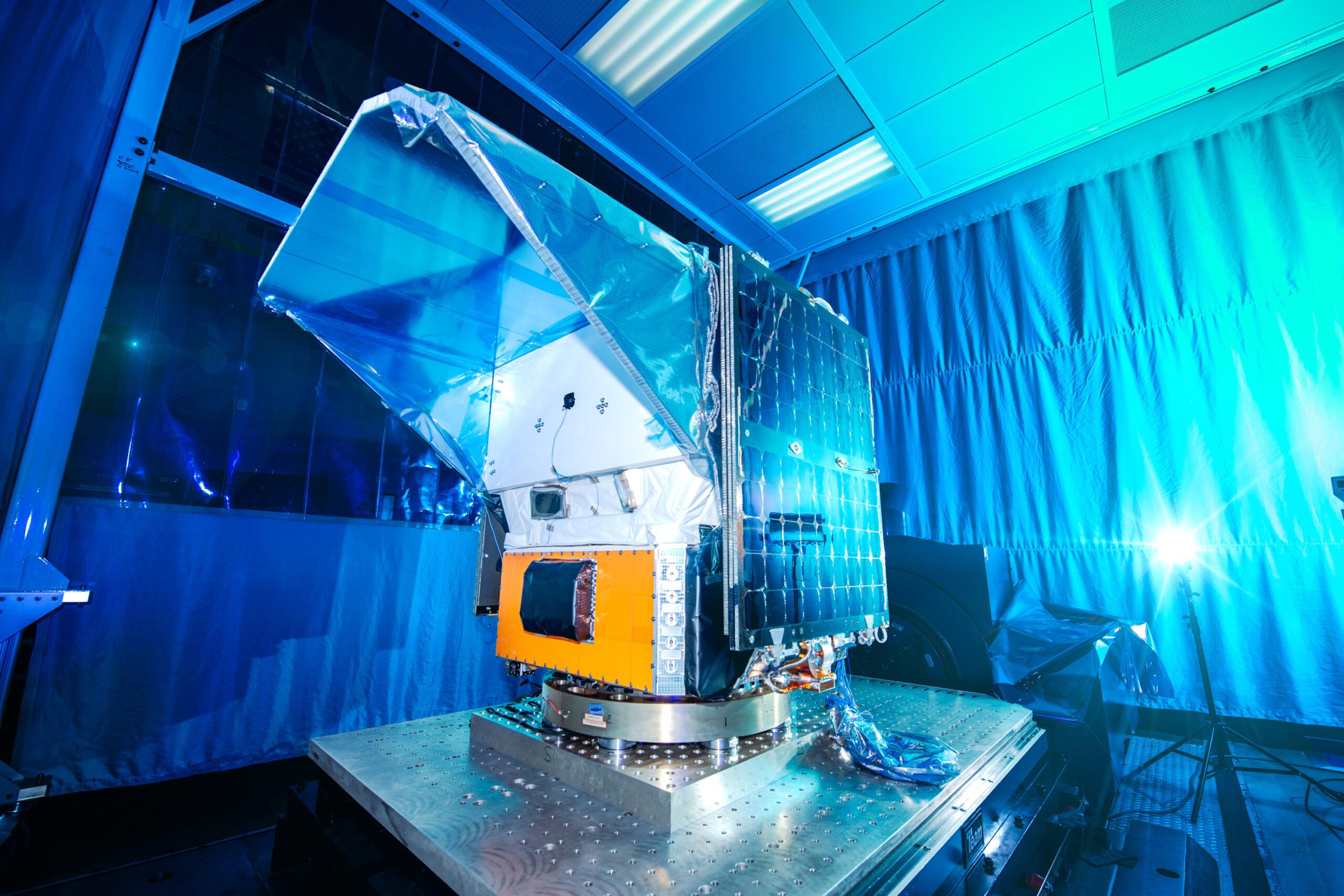

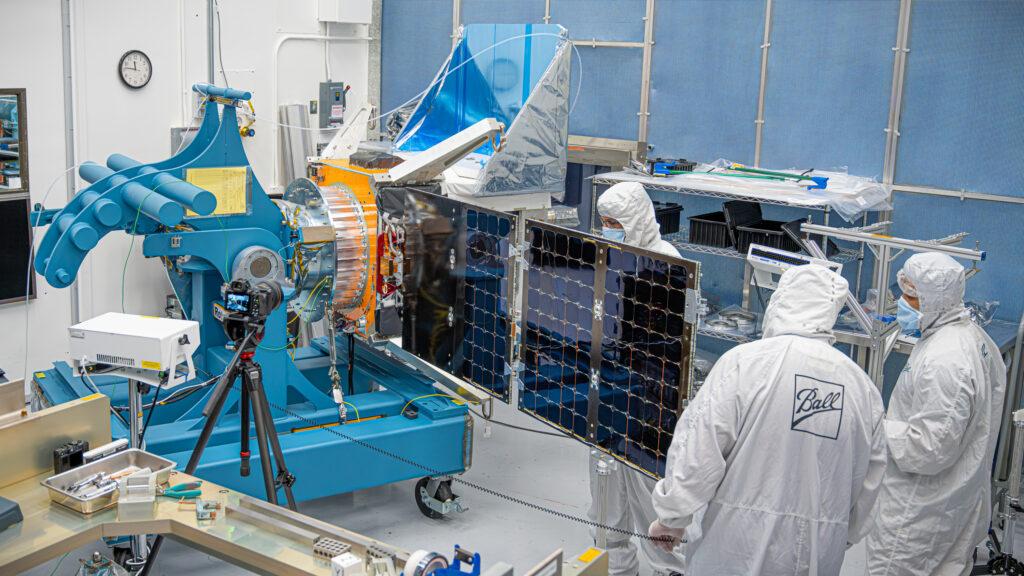

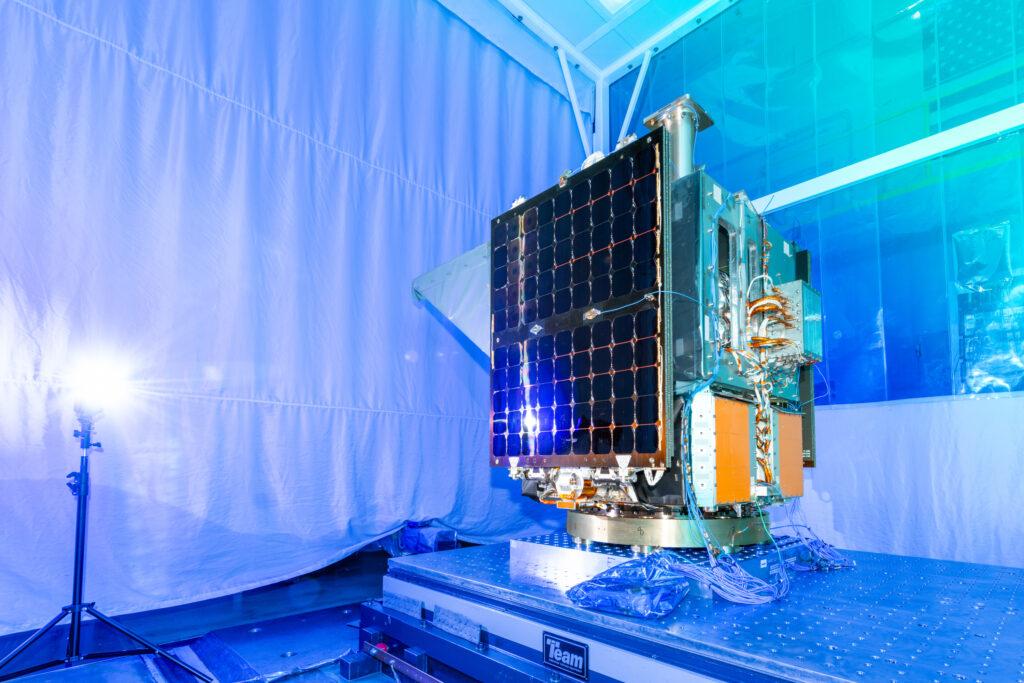

On a recent afternoon, technicians at Ball Aerospace in Boulder prepared the satellite for a final set of tests to simulate the vacuum of space. Each wore head-to-toe "bunny suits" to protect the satellite against dust. Wires around their wrist grounded their bodies to guard against electrostatic shocks.

Through a window into a cleanroom, the spacecraft looked like a high-tech chest freezer with solar panels tucked against its sides. A visor on one end shades a custom-built optical sensor that will scan the Earth every three to four days as it looks for methane’s infrared fingerprints.

Science as an advocacy tool

Jon Goldstein, a senior policy director of legislative and regulatory affairs for the EDF, acknowledged launching a satellite is an ambitious move, but it’s a natural extension of the nonprofit’s previous methane work.

Those efforts kicked off more than a decade ago. As advanced hydraulic fracturing techniques drove a natural gas boom across the U.S., the industry marketed the fuel as a climate-friendly alternative to coal.

Meanwhile, the EDF grew concerned the industry wasn't fully accounting for the climate impact of methane leaks, which is the primary ingredient in natural gas. To get a clearer picture, it collaborated with university scientists to measure emissions with everything from overhead flights to plastic bags tied around pipelines, said Goldstein.

The culmination of the research was a peer-reviewed 2018 report that found methane emissions from the U.S. oil and gas industry were around 60 percent higher than estimates from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Goldstein said the research — co-authored with scientists at prestigious institutions like Harvard and Standford — gave EDF new muscle to push for stricter methane regulations. Those campaigns, he said, helped nudge Colorado to adopt the nation's first set of oil and gas methane regulations in 2014. The Obama administration followed suit with the first federal rules two years later, requiring companies to monitor, plug and capture methane leaks at new drilling sites.

"That understanding prompted the action to get the regulations in place," Goldstein said.

Methane science on a higher orbit

MethaneSAT is an attempt to replicate the work on a global stage.

The nonprofit developed the project with Harvard University and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory before officially launching the MethaneSAT subsidiary in 2018. It raised funds for the project through a series of campaigns, collecting donations from billionaires John and Laura Arnold and a philanthropic foundation set up by deceased hedge fund manager Julian Robertson. A two-year grant from the Bezos Earth Fund provided an additional financial boost.

MethaneSAT differs from existing environmental monitoring satellites in its ability to both pinpoint methane hotspots and identify which countries might be underreporting their emissions, said Hamburg, the chief scientist.

Hamburg said the data, which the EDF will work to analyze and publish in a matter of days, will provide some of the first direct measurements of methane emissions in countries like Russia. He recognizes that's politically sensitive information, which is why the nonprofit plans to share results in conjunction with the International Methane Emissions Observatory, a United Nations project that tracks methane pollution around the world.

Hamburg also expects the results will be of direct interest to oil and gas companies already committed to reducing methane emissions. That includes industry heavyweights like ExxonMobil, which has promised to reach “near zero methane emissions” from its oil and gas assets by 2030.

"Now we'll be able to make the measurements to say, are you actually doing it?" Hamburg said.

A vision for a better oil and gas industry

The prospect of using data to improve oil and gas operations attracted Chris Weaver to the EDF's methane project.

A senior captain with IO Aerospace, Weaver is currently contracted as the pilot for MethaneAIR, a modified Learjet the nonprofit uses to hunt for methane leaks and test the same sensor headed into space.

Earlier in his career, Weaver ferried workers to oil and gas sites across Canada. He said the experience taught him the industry is always focused on its bottom line. If the EDF can find gas leaks, he expects the fear of losing a valuable product will motivate companies to find solutions.

"If capturing methane can be done in a very economical manner, it's gonna work, without question," Weaver said.

That potential alignment is one reason the EDF has focused on the oil and gas industry. Unlike other pollutants, methane is an energy source often used to heat homes and generate electricity. In theory, that gives companies a financial incentive to stop it from escaping into the atmosphere.

“This is really one of those things where there is an opportunity to make enormous progress, and, in the process, not create an enormous economic burden,” Hamburg said.

Xin Lan, a climate scientist with the University of Colorado Boulder and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, supports the EDF's efforts to improve the oil and gas industry but also fears it won’t be enough to slow the rise in global methane levels since 2007.

One reason is her own research on the recent increase. By looking at carbon isotopes in air samples, Lan found the main factor driving the recent uptick is likely natural microbes in wetlands and shallow tropical lakes, not oil and gas operations.

Those findings could be an early sign for a long-feared climate feedback loop, where higher temperatures and wetter weather drive out-of-control warming. And it's why Lan says humanity can’t hesitate to end its dependence on fossil fuels, which remains the main factor behind global warming.

"Reducing oil and gas methane emissions alone is not going to magically save the whole climate crisis. We have to go much further than that," Lan said.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct a sentence about funding from the Bezos Earth Fund. EDF received a two-year grant, not a five-year grant.