In the 1860s, Indigenous people were removed from Colorado’s Front Range and Eastern Plains. As part of that campaign, on one day alone, more than 200 Cheyenne and Arapaho people were murdered by U.S. troops in the Sand Creek Massacre.

Today, Cheyenne and Arapaho descendants are asking why more hasn’t been done to welcome them back to their ancestral lands and heal the traumatic events of the past.

A group called People of the Sacred Land is compiling the true history of what happened to those who were forced out of Eastern Colorado, and proposing ideas — including a Tribal Embassy in Denver — to give their descendants more say in what happens to the lands they used to call home.

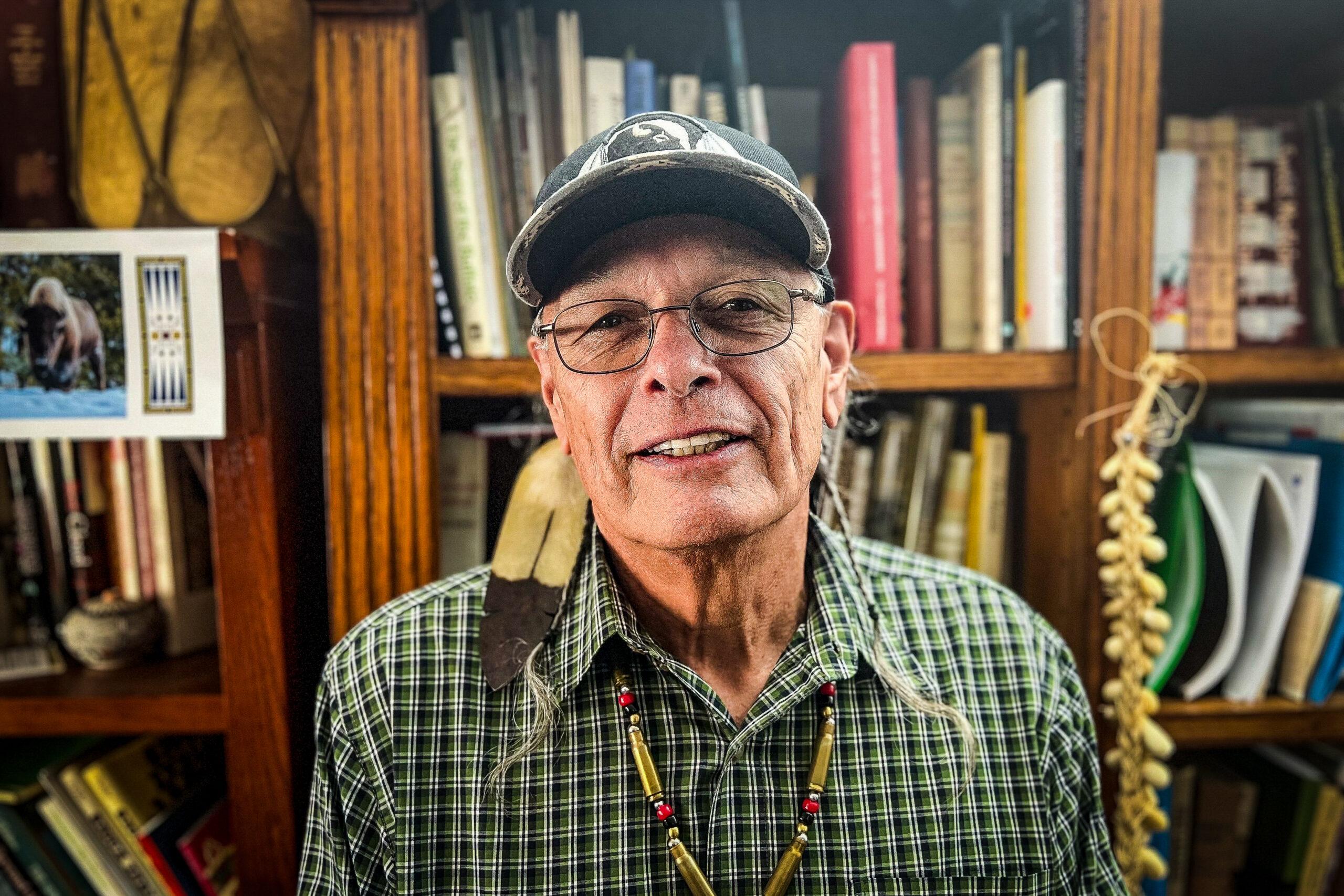

“The idea of an embassy is pretty practical in a lot of ways,” said Rick Williams, who is Oglala Lakota and Cheyenne, and leads People of the Sacred Land.

He said people who have been alienated from their lands need an official capacity in order to be party to decisions made about that land.

“In addition to that, we know that there are at least 200 sacred sites that are unprotected in Colorado,” Williams said. He wants tribes to oversee restoration or preservation of those sites.

“We don’t want people to think that we’re going to be coming after private land. That’s not what this is about. Indian people know what it’s like to have their land taken, and they don’t want to do that to anybody. But there’s plenty of federal land, and there’s plenty of city and county land, and there are opportunities to investigate how to make this happen,” he said. Public universities, including Colorado State University, have also benefited from land taken from Indigenous people.

Williams said Colorado is unusual, since in many cases, reservation lands are in the same general areas where the tribes had lived. That’s not the case with the tribes who inhabited Colorado’s Front Range and Plains. While tens of thousands of people who identify as American Indian or Alaska Native currently live in Colorado’s Front Range cities, there are no reservations in those areas, and Williams believes that needs to be recognized and accounted for.

He told the podcast The Modern West that one tribe is currently exploring how to create a reservation here.

“They’re going to purchase land, and they’re going to call themselves the Cheyenne Arapaho Tribe of Colorado,” Williams said on the podcast.

People of the Sacred Land started after the discovery of a set of dangerous laws that remained on Colorado’s books.

In 2018, Williams started researching his family history, and discovered two orders made by the territorial governor, John Evans, in 1864, that required “friendly Indians” to gather at specific camps, threatened violence against those who didn’t comply, and called for people to “kill and destroy” Native Americans who were deemed hostile by the state. Those orders helped lead to the Sand Creek Massacre, and Williams found the orders were still valid in Colorado.

For years, he campaigned for Gov; Jared Polis to rescind them, which Polis did in 2021.

That discovery helped lead to the creation of People of the Sacred Land. In the past couple of years, the group has drawn funding from local foundations and donors, appointed commissioners and hired researchers.

“We want to know exactly how Indian people were removed from this area, and exactly how much was lost,” the group’s website says. They are currently working on an economic loss assessment.

Their research focuses on the legal and political history of land where tribes — including bands of Shoshoni, Bannock, Utes, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche and Kiowa peoples — used to live. Williams said the group has uncovered details about swaths of land taken by the U.S. government without tribes formerly ceding it.

“We are very, very close to being able to determine who was here, how many people, what was the loss, what were the incidents that have caused them to be removed? And the stories after they’ve gone. That’s equally as important: what happened to them after they were forced out of Colorado?” Williams said.

They expect to release their findings later this year.

Bringing people back to Colorado could mean a lot of different things.

“There’s a whole bunch of ways that I think that we could make it work. But we have to start somewhere,” Williams said.

One idea is to bring bison back to Eastern Colorado, after they were exterminated from the land as part of the campaign to drive away Indigenous people. That could mean purchasing a large ranch, or making an agreement with the National Park Service to co-manage land.

“You first have to look at it from a spiritual standpoint and a cultural standpoint: we understand that that is our brother. We know that when the buffalo thrives, we can thrive. And so that's one of the basic principles of restoration, is that you want to bring back the buffalo,” Williams said, adding that the area could be big enough, with enough animals, to also make a viable business opportunity for tribes.

Denver currently has two herds of bison in its mountain parks, and it recently donated some of the animals to tribal communities out of state.

Another idea, which Williams credits to Rich Tall Bull, a local descendant of Cheyenne Chief Tall Bull, who was killed by U.S. troops, is a cultural center on the Plains. It would be home to bison and horses, and house an educational center for Coloradans and tourists.

By uncovering legal and political details long hidden in the past, and bringing that information to Coloradans, Williams hopes to create momentum for some kind of restoration.

“It shouldn’t be just about us wanting something to happen. It should be the good people of Colorado,” Williams said.

“This should have happened a hundred years ago, 150 years ago. Those people should have been brought back to their homeland in a good way, instead of alienating them.”