It’s a four-mile hike to get there. A sandy trail works its way south, an expanse of San Luis Valley sagebrush plain to the right as it hugs the Sangre de Cristo Mountains on the left. After two miles, the high desert landscape is briefly interrupted by a wall of greenery — towering cottonwoods living on the banks of narrow Deadman Creek.

The path turns west into the foothills, up to a solitary cabin. The logs are squared and carefully notched at the corners to lock together. Inside waits a cast iron stove, wooden cabinets with supplies, a dining table with chairs and four bunks.

The cabin is more than 140 years old.

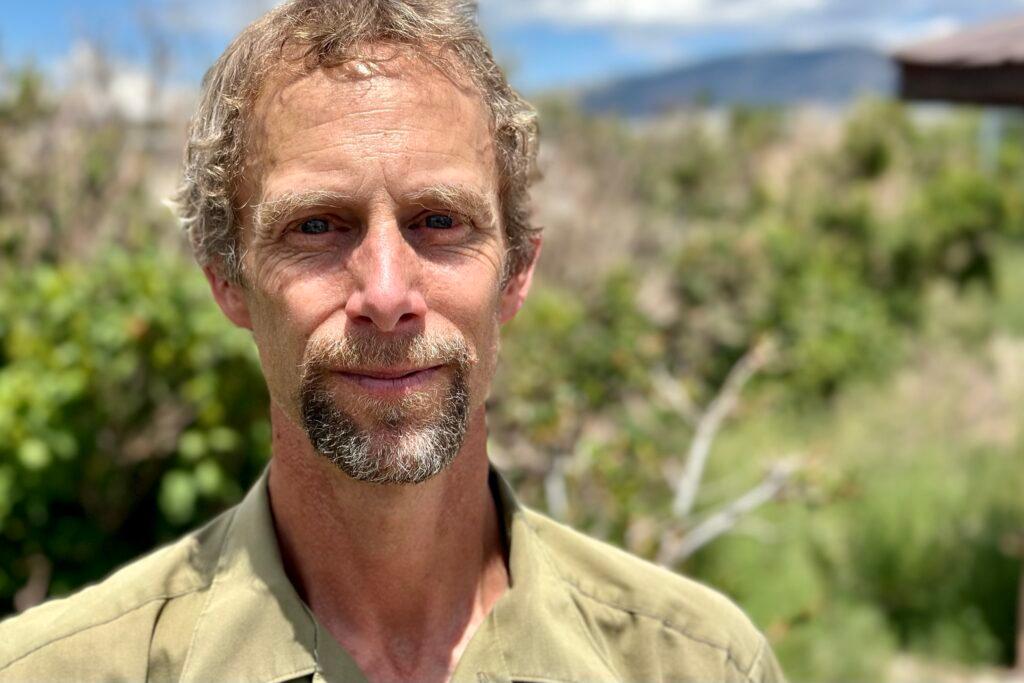

“Sometimes, you’re near an archeological site or a historic site where it’s not even close to seeing the landscape the way it was when it was occupied,” said Rio Grande National Forest Archaeologist Price Heiner. “You’re going to get it there, at Duncan. It’s just super neat.”

The Duncan Cabin — estimated to have been completed in 1880 — stands as the lone remaining structure of the town of Duncan, population — at one time — 250. In late June, after extensive restoration, the U.S. Forest Service opened the cabin up for public rental.

John Duncan, the gold miner

John Duncan was, like so many of the Colorado Gold Rush, hopeful of striking it rich. But, his find came a solid decade after the establishment of major mining hubs like Idaho Springs and nearby Central City or Breckenridge and lay more than 100 miles south of them.

In about 1874, Duncan found gold ore at the mouth of Pole Creek and built the sturdy, one-room home that still bears his name nearby. The ore was not especially rich with the precious metal, but it didn’t stop word spreading, and it didn’t stop Duncan from selling lots on land he thought he had purchased.

“People were slowly, apparently, trickling in,” Heiner said. “Just building cabins in and around his, and eventually it grew up to about 50 structures at its height.”

Duncan became an official town in 1892. Heiner said it had a dry goods store, a newspaper, a freighting company and two saloons. There was a post office and telephone service.

The town did not last long.

The Baca Land Grant

Prior to the United States taking the San Luis Valley in the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican-American War, the Mexican government had continued the Spanish practice of issuing land grants to encourage settlement in remote areas. As part of the treaty, the U.S. pledged to honor those land grants, including the enormous Baca Land Grant in New Mexico.

But, the agreement didn’t go so smoothly. A 2000 article from Colorado Central Magazine details:

“Before the surveyors could set the Baca grant’s formal boundaries, squatters and homesteaders had sprouted. Rather than go through the hassle of evicting them in 1860, Congress offered Baca’s heirs a deal — they could select five 100,000-acre grants elsewhere in the public domain.”

One of those 100,000-acre plots chosen by the heirs lay at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, on the eastern edge of the San Luis Valley. William Gilpin, Colorado’s first territorial governor, purchased the land in 1862, for 30 cents an acre.

George Adams, the cattle rancher

The plot became the “Baca Ranch,” and it changed hands several times before landing in the ownership of cattle rancher George Adams in the mid-1880s.

John Duncan had made his discovery in Pole Creek in those intervening years when the ranch was changing hands. It took until the turn of the 20th century before Adams had fully surveyed his land and determined the new town of Duncan sat inside the boundary of the Baca Ranch.

“(Adams) said ‘All you guys are squatting on my property,’” Heiner said. “So, of course, they said, ‘No way, we bought these lots, these are ours.’”

Duncan thought he had legally purchased the lands from the state of Colorado. Nevertheless, U.S. marshals evicted the residents. Adams paid homeowners $125 for each building they had on the land. He then offered to sell the homes back for $10, provided they moved the structure off the ranch.

After nearly a decade of legal wrangling over Duncan’s ownership that ascended all the way to the top of the American judicial system, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Baca Ranch, and the town was gone.

But the Duncan Cabin remained

Duncan, the community, did not have the chance to become a ghost town. The structures that weren’t moved off-site were razed. Old foundations still can be found on the landscape, along with century-old broken glass and rusted iron.

However, George Adams appreciated the craftsmanship in the home built by the town’s founder and decided to keep it around as field housing for his ranch hands.

Duncan, the cabin, thus survived. The ranch changed hands multiple times, was broken up and subdivided, but the cabin stood. Eventually, the Nature Conservancy bought the land and it was given to the U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Great Sand Dunes National Park.

In 2011, the Forest Service contracted with Colorado-based nonprofit HistoriCorps for a meticulous restoration of the cabin. It was taken apart, log by well-hewn log. Rotten wood, mostly just at the base of the structure, was discarded and replaced with new logs hewn in the same way using traditional tools. Then, it was rebuilt to look much as it would have, apart from new windows, new doors and a new roof.

“We’ve been going there, cleaning it, fixing it up,” said Matthew Schomburg, a recreation management specialist with the Saguache Ranger District. The nearby corral from the land’s ranching days makes it a rare Forest Service cabin the public can reach on foot or by horseback.

Staying there overnight, as this reporter did — miles from civilization in an area renowned for its dark nights — also feels like it might have felt for a man nearly a century and a half ago, gazing up at the stars and imagining the possibilities.