For the next two weeks, a little patch of Colorado’s Eastern Plains is, for all intents and purposes, the moon.

On a cloudy Monday in Watkins, Colorado, a small town about 24 miles east of Denver, students and professionals alike worked together to simulate what could one day become a normal part of manufacturing.

“We're simulating a lunar mining operation and this test actually is going to take place over 15 continuous days,” Colorado School of Mines professor George Sowers said.

The simulation is part of NASA’s Break the Ice Lunar Challenge, which was created to incentivize companies and universities to develop new technologies and ideas to help further the space mining industry.

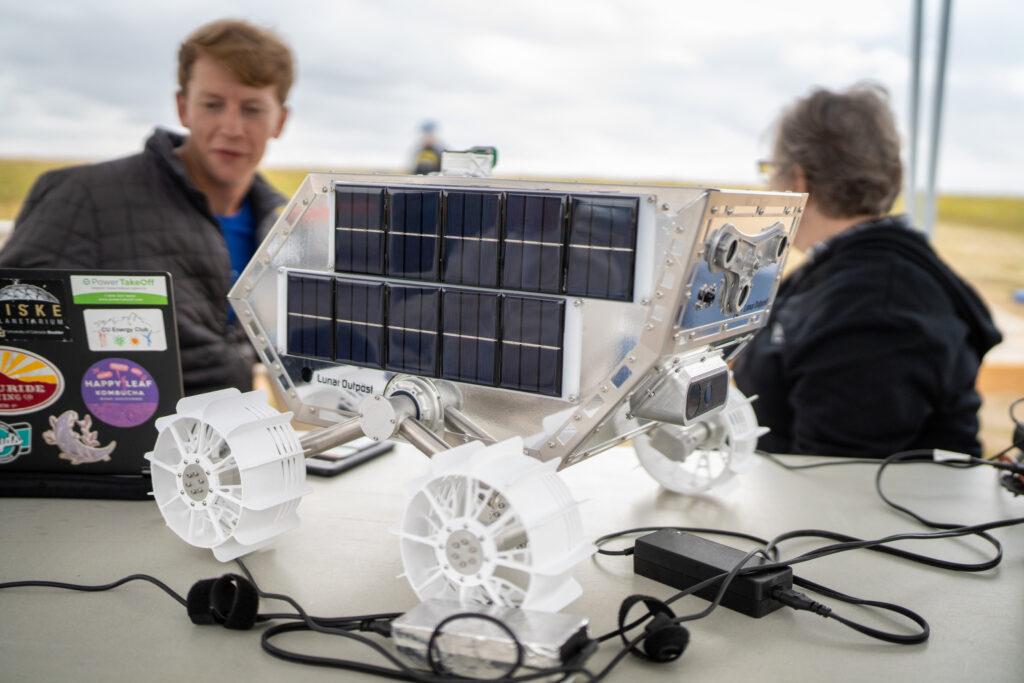

Students at the Colorado School of Mines have partnered with Lunar Outpost, a space exploration company based in Arvada, to tackle NASA’s challenge. Together, a team of about 40 people — nicknamed the Ice Diggers — designed two rovers that can drill into solid ice and haul pieces back to an outpost.

“It's a working class robot,” Sowers said. “It's a working robot that would generate economic returns. If we had water and ice on the moon, that would be an extremely valuable commercial commodity.”

Each team has to prove their rover can excavate and transport about 1,700 pounds of low strength concrete, the material they’re using to simulate ice. The rover must also make multiple 530-meter trips to simulate the trip between an ice deposit and a lunar outpost. If successful, NASA may choose the Ice Diggers’ rover to participate in an on-site competition for a shot to win $1.5 million in prizes.

Forrest Meyen, a co-founder of Lunar Outpost, said the work they’re doing will be vital for when humans start to live on the moon.

“Really our goal is to mine the surface of the moon for the rare earth elements there, for some solar implanted volatiles, like rare gasses like helium three or also water, which on the surface of the moon is like liquid gold,” he said. “Water can be used not only for astronauts to breathe, but it can be broken into hydrogen and oxygen for rocket propellant to send missions to other places in the solar system or even to be used to refill satellites back at Earth.”

For many students, working on the rover has been a highlight of their career. Darin Meeker, a second-year Ph.D. student at Mines, said working on the competition has been a welcome change of pace from his mostly theoretical work.

“This has to do with my research for my Ph.D. because this is one of the use cases for the wireless power transfer technology that I'm working on,” Meeker said. “So this is really cool to see and kind of seeing where the technology is going in this field. It's good to know for our research.”

Even if the Ice Diggers win NASA’s competition, don’t expect their rover to be stowed away on the next rocket to the moon. They’d have to make major modifications to protect it from radiation, moon dust and other space-travel-related hurdles. But that’s not stopping the team’s enthusiasm.

“If they told me tomorrow to go up to the moon I'd do it,” Meeker said.

A winner for this phase of the competition will be announced in December. The final phase of the competition is scheduled for May.