In 1974, a young trail runner from Ouray stood at the corner of Main Street and Third Avenue, where he liked to start his long runs, and decided to do something no one ever had: run all the way to Telluride over a rough mountain road.

“What made me do it was I just wanted to see if I could do it!” explained Rick Trujillo, now 75.

He’s still shocked that he ended up inspiring one of the most beloved races in Colorado.

The 50th running of the Imogene Pass Race was held over the weekend, taking participants 17.1 miles over a steep mountain pass, more than 13,000 feet above sea level. Trujillo likes to say he started the race “by accident. It was “just” a training run for the Pikes Peak Marathon, which he would end up winning five times.

“I turned into an old-timer now. I can’t believe it!” he said, with one of his quick, big smiles. “I remember things people have no idea about, but they’re fresh in my memory.”

Trujillo remembers a world in which Ouray used to have five grocery stores, back when the nearby Camp Bird Mine was open and still very active. He also remembers how, by the 1970s, his hometown had much less traffic and many more empty storefronts, as mine operations were winding down.

Ouray, which is so squeezed by skyscraper mountains that it calls itself the Switzerland of America, is now a busy tourist destination, with tons of off-road vehicles tackling Imogene Pass whenever it’s not covered in snow.

But during Trujillo’s first run over the pass, “I saw nobody!” he exclaimed.

Driving his old Subaru, Trujillo showed off the route, which starts on a paved road that quickly turned to dirt as he left town.

Pine trees and aspens hugged the roadway, rocky peaks in the distance. Trujillo gave a tour that was part course description, part history lesson.

He passed by cottages and cabins, some humble, some fancy. None of them, he explained, were there in the 1970s, before Ouray was “discovered.”

“But you have to keep in mind that in the mining era, in the 1880s and ’90s and early 1900s, miners and prospectors lived everywhere in these mountains. So these new houses are nothing new, so to speak,” he said, with a little chuckle.

Trujillo drove past the closed mine bordered by a dilapidated Victorian home and old schoolhouse, where the school bus used to be a Jeep Willy plastered with homemade signs. He passed by campgrounds that didn’t exist in1974.

“OK, we’re approaching mile five," he said. “Remember it’s 10 miles to the top from the Ouray side. Ten miles and 50 yards, something like that.”

If anyone would know the exact number of yards, it would be Trujillo.

As the road got rougher, he seemed completely unfazed.

“Hey! This is a good road!” he said, laughing, his car lurching and bumping over bedrock. He dodged deep potholes that looked like they were filled with milky coffee.

Eventually, just before mile six, he pulled off and parked, not wanting to “tear up” his car.

“OK, this is where it starts to get rough,” he said, power walking with seemingly no struggle up the steep grade, into increasingly thin air.

He talked about his first time running this pass as if it was no big deal.

“Hey, I was in my 20s. I’m now 75. I now understand it requires some work to do this stuff,” he said, with more laughs. “But in those days it just came naturally.”

He ran without any food or water.

“No, I never gave it a thought.”

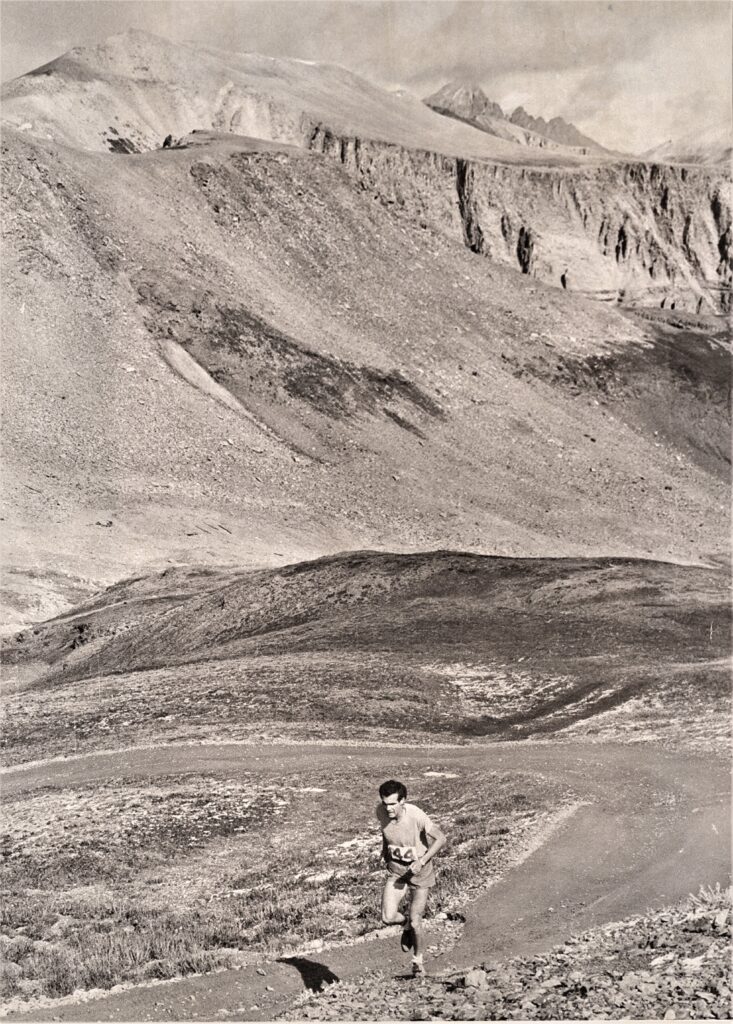

Trujillo remembers he just kept moving, up through the switchbacks, meadows giving way to rock walls and deadly drop-offs. Toward the top of the pass, he found an almost-all stone world, with jagged rock faces ahead of him. At the summit, there was a sea of mountains all around him.

On a clear day, “you can see the La Sal Mountains in Utah, the Abajo Mountains in Utah,” he said. “On a really clear day, you can even see the Henry Mountains, over by Lake Powell.”

The course is knock-your-socks-off beautiful — and astonishingly hard, despite what 26-year-old him thought at the time. Every year at the race’s course briefing, he drills one acronym into the runners: IFM.

Incessant Forward Motion

“As long as you’re moving forward, you’ll get to the end, even if it’s at a crawl. But if you stop, you may never get to the end,” Trujillo said.

In 1974, he did get to the end: Telluride, a touch more than 17 miles away.

“And I just had my shirt, shorts and running shoes,” he said. “That’s it!”

No money, no ride home. A friend who was supposed to meet him had gotten lost, “having taken every road except Imogene Pass.”

That’s when Trujillo crossed paths with a couple of locals he knew, locals who were shocked when they heard what he had just accomplished.

“Because no one had ever done that before,” Trujillo said.

Pretty soon, one of those men, fatefully named Jerry Race, decided to approach the chamber of commerce with a proposition.

“The race was not my idea!” Trujillo insisted. “It was a gimmick by the Telluride Chamber of Commerce to try to get people to come to Telluride.”

As hard as it is to believe now, back then, Telluride was “just a run-down mining town at the end of a dead-end road.”

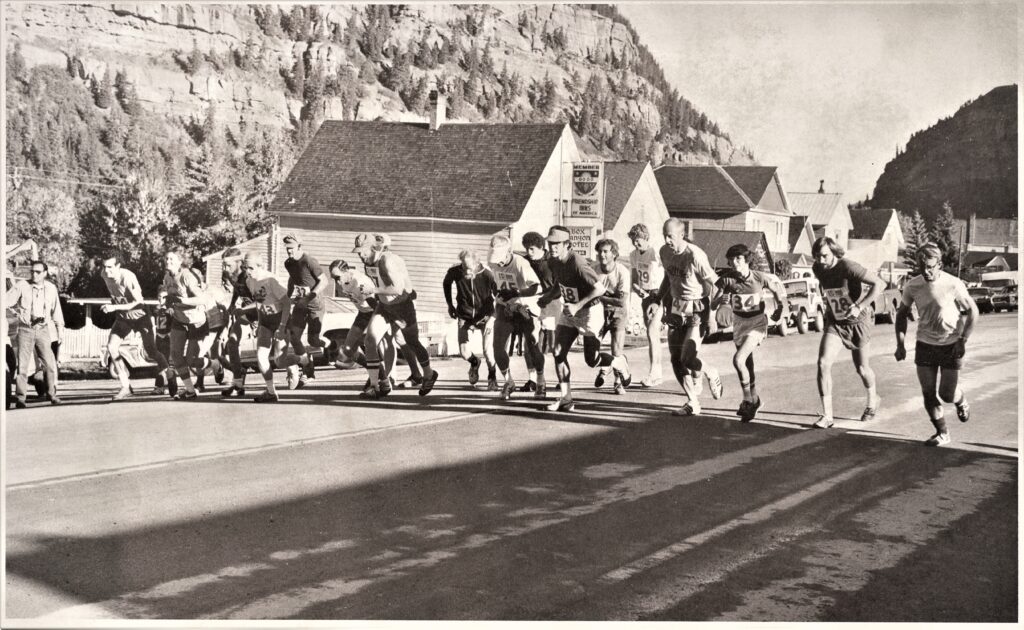

That first race was held the very next month. Trujillo won, easily. There were only seven runners, six finishers — and zero aid stations.

“You left Ouray, you didn’t see anybody or anything until you got to Telluride, in those days,” Trujillo said.

Now, registration is capped at just more than 1,500 runners. But at its heart, the Imogene Pass Race is still wild. Over the years, runners have had to dodge falling boulders and push on through swirling snow.

“And as they say in the disclaimer: If you don’t like it, you can’t handle it, you have no business being here,” Trujillo said, matter-of-factly. “The mountains don’t care. They’ll wipe you out in a minute, in an instant, if you give them any chance at all.”

Even though the race can be so unforgiving, or maybe because of that, it’s become incredibly popular. This year, it sold out in 13 minutes, a new record.

Trujillo could never have imagined any of this. He called it “just astounding” how much the race has evolved through the decades.

“I’m amazed that we’re still doing this. I’m also amazed that this first run was 49 years ago. I can’t believe it!” he said, his eyes big and crinkled with joy. “And we’re still here.”

He’s still helping organize the second-oldest running race in Colorado, even though this year, Trujillo chose to sit out running in it, as he nurses an injury. He hopes to be back next year, though — and to keep running these steep local trails as long as possible.

“I like being in the mountains, this is my home,” he said, “even though I know they don’t care.”