The Colorado Department of Transportation is rolling out a new method of setting speed limits that tends to lower them.

Traditionally, U.S. traffic engineers use the “85th percentile” method that sets limits at the speed at or below which 85 percent of drivers travel in normal conditions. This federally approved approach has been used by state and local transportation agencies since at least the ’60s, but street safety advocates and city transportation officials deride the method because it usually leads to higher speed limits and faster speeds, which is associated with more serious crashes.

CDOT engineers are now embracing a new technique that allows state traffic engineers to weigh other factors more heavily while setting speed limits on state-controlled roads and highways. Those include the road’s purpose, geometry and the number of pedestrians and cyclists who use it.

It’s similar to a proposed change to the federal road design standards and has spread the status quo 85th percentile method for decades. The shift in Colorado also comes as traffic deaths and injuries — especially of pedestrians and motorcyclists — continue to rise across the state.

“Colorado is one of the first to make the shift,” San Lee, CDOT’s state traffic engineer, said of the new speed limit approach. “We want to make sure that we're effective and improve safety.”

Between 50 and 60 miles of roadway have been evaluated under the new process, and about two-thirds of those studies have resulted in lower speed limits. Just one has resulted in a higher speed limit. CDOT engineers started using the new method two years ago and plans to fully adopt it in 2024.

“We’re hoping to do it for every speed study [request] that we get from a local agency,” said Benjamin Acimovic, who oversees CDOT’s speed management program.

Some of those new lower speed limits will soon be set in downtown Loveland.

More than a decade ago, CDOT raised the speed limit on part of U.S. 287 in Loveland— which also doubles as that city’s main downtown streets — after an 85th percentile speed limit study. CDOT reportedly made that shift from 30 mph to 35 mph without informing the city’s then-director of public works.

In 2022, Loveland city officials asked for another speed limit study of U.S. 287. This time, CDOT found that more crashes happened after the higher speed limits were introduced a decade ago. The 85th percentile this time had risen to 42 mph.

Under the old regime, the speed limit would be raised again. But instead, CDOT and the city are planning to lower it back to 30 mph. And in the heart of downtown Loveland, it’s going even lower: 25 mph.

“Amen,” said Sean Hawkins, director of Loveland’s Downtown Development Authority. “It needs to happen.”

Hawkins said he’s seen many near-misses between pedestrians and vehicles on North Lincoln and North Cleveland avenues, a pair of one-ways that together double as the highway. City officials say there’s been one pedestrian death in the immediate area since 2018.

Beyond safety concerns, he said lower speeds will make spending time downtown far more pleasant. A nearby rooftop patio is “wonderful,” Hawkins said, “But sometimes you can’t hear up there because the volume of the road is too much.”

As a driver himself, Hawkins said he understands the urge to speed. But the 5 mph in the heart of downtown isn’t going to cost drivers much time at all, he said. “Twenty-five is perfect,” he said.

Lower speed limits also fit into the city’s push for a more vibrant downtown, said city traffic engineer Nicole Hahn. She’s grateful for CDOT’s cooperation.

“I would say that it’s an evolution that I’m seeing from CDOT,” she said. “We have our standards … but I think we’re interpreting some of those things in a way that is evolved from the standard traffic engineering practice.”

Another change in a more rural setting has some locals upset.

Speed limits won’t change overnight on every road across the state. Instead, the impact of the new method will become clear over time as more local governments, like Loveland, ask the agency to perform speed limit studies or when CDOT uses it after road construction projects.

That happened recently on U.S. 36 between Lyons and Estes Park. CDOT rebuilt much of the road after the 2013 floods heavily damaged much of that road. In doing so, engineers had to build in a new curve within a curve to accommodate a change to the ground below.

Eventually, CDOT noticed commercial trucks were going off the road there with alarming regularity.

“When they would go around the curve, they couldn't adjust for going that higher speed and they would go off the roadway,” Acimovic said.

An 85th percentile analysis found most drivers were traveling at 54 mph through that trouble section. But CDOT staff decided to lower the speed limit to 40 mph based on its geometric challenges.

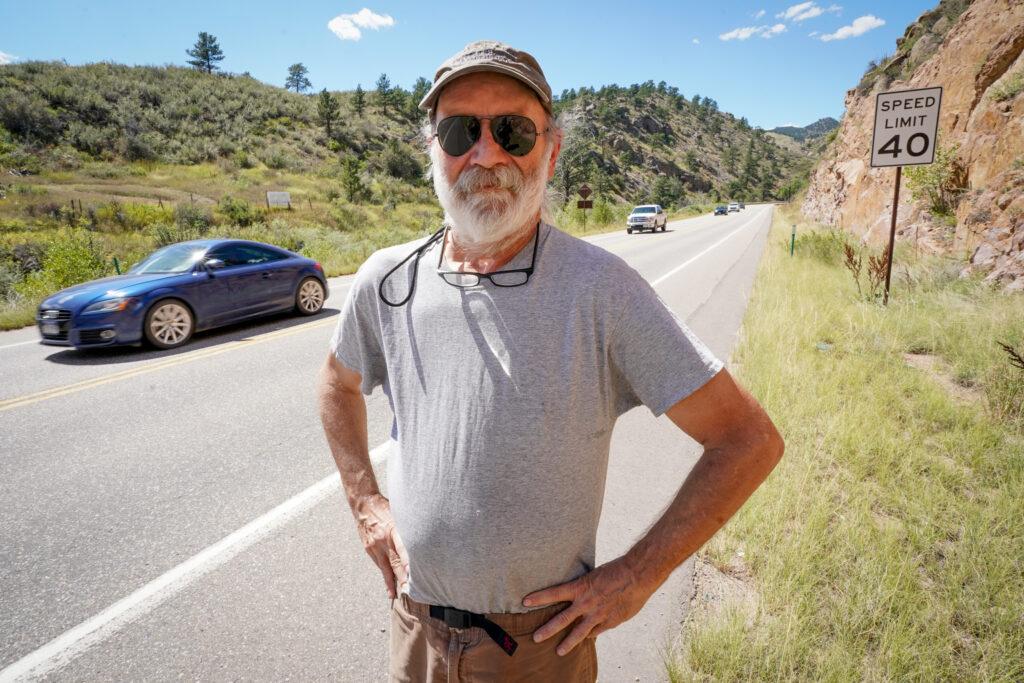

That hasn’t gone over very well with locals who use the road often, said Warren Musselman, who lives in nearby Pinewood Springs. They know how to drive the road and tend to do so quite quickly. The problem, he said, arises when tourists and drivers of heavy trucks use the road — and obey the new lower speed limit signs.

“I think that the lower speed limit has actually made it more dangerous because you have greater speed differentials that are occurring between local residents who drive the road at 50, 55, 60, and you've got people who are driving 40,” Musselman said.

Other local residents expressed similar concerns in response to a question CPR News posed in a private Facebook group.

The dynamic of speedy locals and plodding tourists and trucks is somewhat common across Colorado’s mountain roads, Acimovic said. But so far, the changes on U.S. 36 appear to be making the corridor safer.

“It is a challenge and it may feel more dangerous,” Acimovic said. “But … the crash rates are not reflecting that feeling.”

CDOT does have a few strategies to help avoid wide gaps in travel speeds on mountain roads. Some multilane highways restrict big trucks to the right lane. Others have two speed limits — a higher one for personal vehicles and a lower one for commercial trucks.

Another effective, if unpopular, strategy is enforcement. State law has historically tightly restricted where automated speed cameras can be used. But a new law signed in June unwound those restrictions. CDOT and the State Patrol are exploring how they might use them across the state, Lee said.

“It's definitely a strategy or tool that we want to put out there,” he said.