Editor’s note: This story describes violence. Reader discretion is advised.

Nancy Stark and her husband retired to southern Colorado three years ago. They lived off the grid for two years before moving to an apartment in San Luis. During her short period of time in the San Luis Valley, Stark became fascinated with the “Bloody Espinosas” — the brothers who went on a killing spree throughout the Colorado territory in the 1860s.

The Espinosas’ path of terror ended when a famous tracker killed and then beheaded them. It was said their heads were put on display in Fort Garland. So, Stark emailed us and wondered what happened to their heads.

Who were the Espinosas?

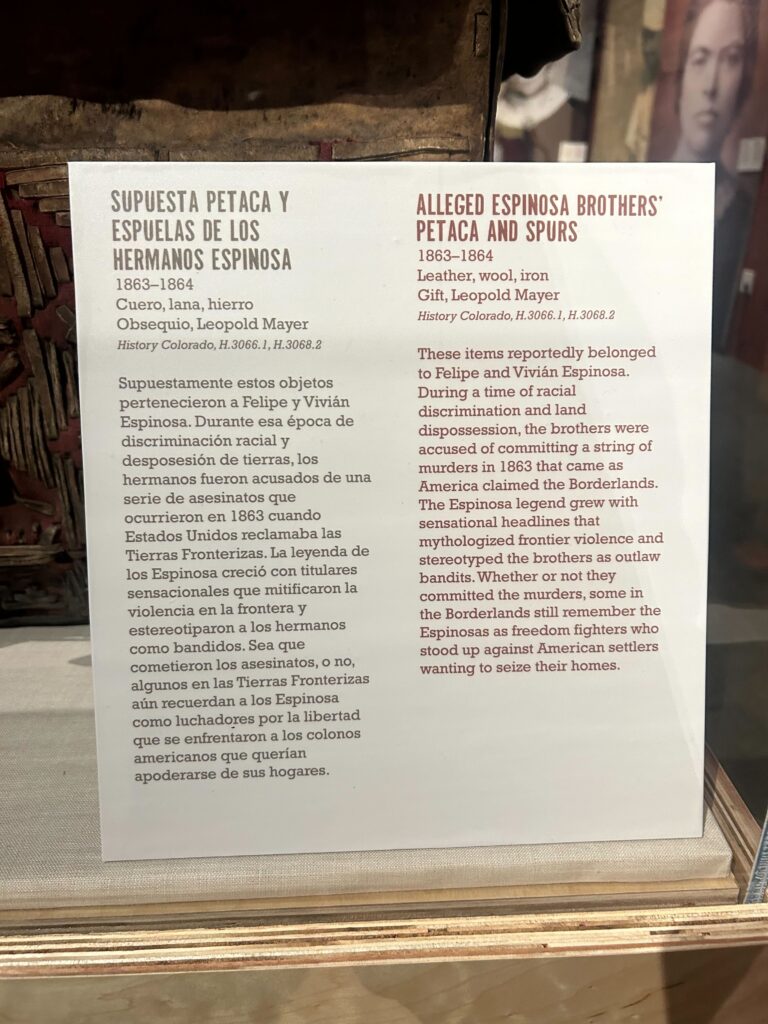

The Bloody Espinosas were brothers Felipe and Vivian, and later nephew José. Their family grew up in what was once Mexican territory. After the Mexican-American War in 1848, their land was ceded to the United States.

Author Adam James Jones grew up in South Park. The story of Espinosas came up during his seventh-grade Colorado history class. Jones researched them since he was an undergrad at the University of Northern Colorado. His research led him to write an essay and the novel “The Vendetta of Felipe Espinosa.”

Jones said the Mexican-American War may have set off their killing spree.

“There's a lot of belief that his family suffered some abuse shortly before the killing spree started, and this could very well have been the cause,” Jones said. “It could be that the sisters and his mother and some other family members experienced some abuse by soldiers out of Fort Garland in the early 1860s.”

Former Rio Grande County Museum director Louis Coleville gives another reason in History Colorado’s podcast called Lost Highways: Dispatches of Shadows of the Rocky Mountains. The episode, “Beyond a Valley of a Doubt” tells the story of the Espinosas.

Coleville also said the Espinosas lived peacefully in the territory until they came home one day to find their family murdered and their house burned to the ground.

“Having your family destroyed while you were gone and your home, it would lead you to some violence and it was a period of time when there was violence,” Colville said. “You had just come through the Mexican War. You didn't cross the border, the border crossed you."

The Killing Spree is on

Felipe and Vivan engaged in petty crimes such as highway robberies. It is believed that their killing spree began shortly after they robbed a well-known priest who was traveling from Galisteo. Instead of killing him, they tied him upside down to a wagon tongue and then whipped the horse. The priest survived the dragging and reported it to the nearest military post in Fort Garland.

U.S Marshal George Austin and a group of soldiers attempted to get the brothers to come to Fort Garland from their cabin near San Rafael. Under the guise of a recruiting trip, the group tried to get them to go back to Fort Garland without confrontation. But a gunfight ensued. A corporal was killed. The Espinosas escaped. But their private war was on.

The Espinosas reportedly killed an estimated 32 people throughout their rampage. Felipe sent a letter to Colorado Territory Gov. John Evans threatening to continue the killing if he was not pardoned for his crimes. He said he would kill 600 white settlers, 100 for each family member lost at the end of the Mexican-American War.

The Espinonas were not easy to track down. Jones said the South Park region was very spread out during that time, which made it difficult to find them. He said people were living in mining camps that were dozens of miles away with no well-defined roads.

“They would sneak up on their victims and sometimes watch them for many hours during the day until they were alone,” Jones said. “And then, they would go and commit their murders. In some cases, the corpses weren't discovered for a long time after they had actually been shot. And by then, the Espinosas were many miles away.”

Matthew Metcalfe was the first victim to escape the Espinonsas during their rampage. The brothers tried to kill the lumberman while driving a team of horses through the California Gulch. Metcalfe was shot through the chest. He survived thanks to a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation stuffed in his front pocket.

Metcalfe identified the two men. A posse found the brothers outside of Cañon City. Vivan was killed, but Felipe survived. The next several months would be quiet. Then the killings resumed. This time Felipe recruited his 12-year-old nephew José.

Tobin finds the Espinosas

Col. Samuel Tappan called on well-known tracker Thomas Tate Tobin to find the Espinosas. Tobin was a close associate of Kit Carson, Wild Bill Hickok, and Buffalo Bill Cody. He had worked as an Army scout and courier. Jones said he was the real deal.

“It was said of him that he could track a grasshopper through sagebrush,” Jones said. “Tobin also had a big role in the Taos Revolt that occurred in 1847. He is one, I believe, of just two people to survive the assault on Turley's Mill outside of Taos.”

The Espinosas had captured a woman named Dolores Sanchez and a man named Philbrook. Both were tied up but managed to escape. Sanchez was picked up by soldiers and taken to Fort Garland where she identified the Espinosas. Jones said Tobin was able to track down the Espinosas camp with the help of circling magpies.

“He knew that there had been a kill because these magpies were circling some sort of dead flesh. And when Tobin approached, got a little closer he saw that the Espinosas had butchered an ox and were eating the ox,” Jones said.

Tobin reportedly shot Felipe in the side and then a fleeing José. Tobin then beheaded both.

Jones said Tobin returned to Fort Garland with the heads.

Where are the Espinosas’ heads?

It was said that the severed heads of the Espinosas were on display in Fort Garland. But now, their location has become a mystery. Jones said no one knows for sure where they ended up.

“It was said that the heads were pickled in a big jar of whiskey and were kept on the desk of the editor of the Fairplay Flume,” Jones said. “For a while, it was said that the heads were also preserved and displayed in Fort Garland for a period of time. And then they kind of disappeared from history for a while.”

Jones said they could’ve ended up in the state Capitol. A few years ago, he was giving a presentation on the Espinosas for the Colorado Historical Society at the Byers-Evans House in Denver when two employees approached him.

They said, “It's so funny you mentioned this because a few years ago we were cleaning out the basement of the Capitol and we found two skulls that were unidentified. We didn't know who they were, and so they decided to incinerate it,” Jones recalled.

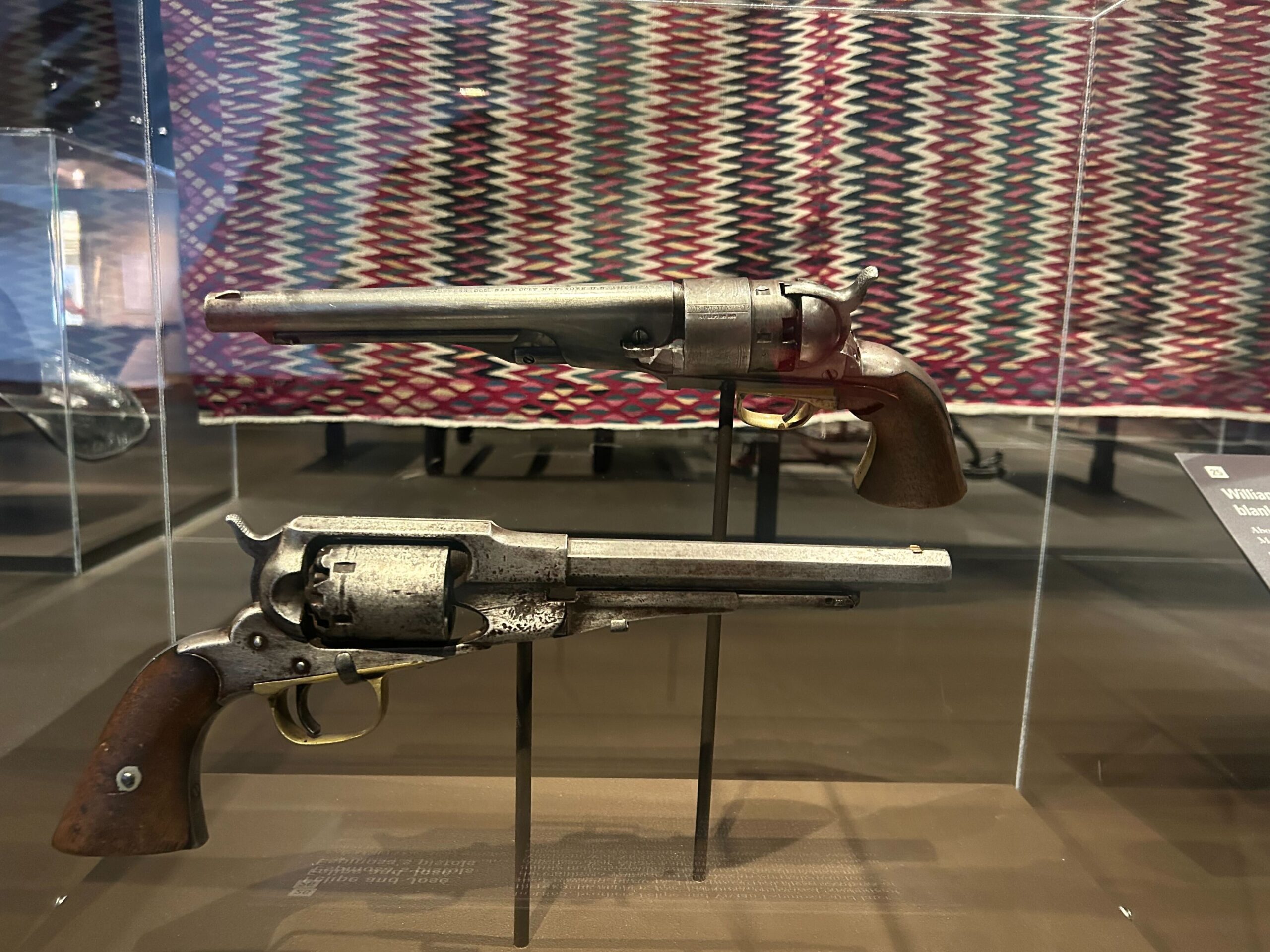

It was never confirmed if the skulls were those of the Espinosas. But artifacts can be found throughout museums in Colorado. The Espinosas’ pistols, a trunk, and spurs are on display at History Colorado Center in Denver. Another set of Vivian’s spurs are on display at the Pioneer Museum in Colorado Springs.

Editor's note: History Colorado is a financial supporter of CPR, but has no editorial influence.

This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Nancy Stark.